Friday, April 25th was World Malaria Day! This is a date designed to raise awareness and funding for malaria- one of the Big Three” diseases that together account for one out of every ten deaths in the world. (The other two are tuberculosis and AIDS). This year, the theme was: “Invest in the future. Defeat malaria.”

And malaria definitely deserves more attention and research. Every year, more than 200 million people are infected and more than 600,000 people (mostly children under 5 years old) are killed by this disease. That’s about 20 times the number of students in Penn State!

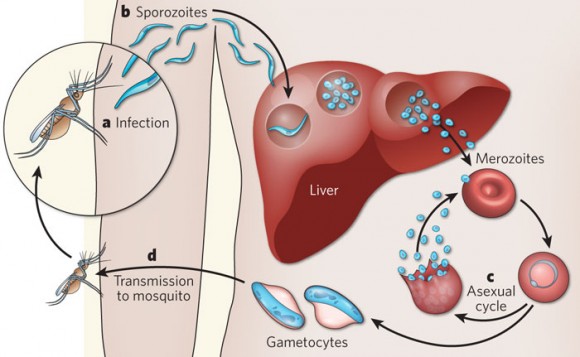

The parasite that causes malaria is also harder to study than many others because it has such a complex life cycle. It does completely different things depending on whether it is inside a mosquito, in someone’s liver, or in their bloodstream. So researchers have to decide the exact part of the life cycle they will focus on, and consider many other ecological and social factors when talking about the disease (since mosquitoes are the main carriers). As if that’s not complicated enough, it also infects monkeys and other animals that can come into contact with people, so only treating the disease in humans wouldn’t eradicate it.

The main symptoms of malaria include nausea, fatigue, fever, chills, muscle pain, and an enlarged spleen. However, some people may develop a more serious set of complications when the parasite invades the brain– they can get hallucinations, slip into a coma, and die. As of now there is actually no way to determine which patients are at risk for these dangerous types of malaria. And so many children who have a high chance of dying are just sent home with mild malaria medication.

However, a study was published just last Wednesday about a pretty amazing discovery— researchers in Sweden have found 13 proteins that are present in the blood samples of patients with the lethal form of malaria, but are much less common in patients with mild malaria.

“Our results indicate that there is muscle tissue that is broken down, particularly in patients who have cerebral malaria (the lethal type) — something that does not occur in patients who have lighter malaria variants,” explains Dr. Nilsson, a professor at the university that published the paper. Apparently the byproducts of muscle breakdown can be identified from blood tests.

This discovery has pretty awesome implications– physicians would be able to easily identify children with deadly malaria, and then care for them accordingly. And the local governments of malaria-stricken countries (and US agencies like the FDA) don’t require approval for testing blood samples, so this can happen very quickly. If this really works, the mortality rate of malaria could be reduced drastically. World Malaria Day has definitely gone well this year.

Sources:

http://www.webmd.com/a-to-z-guides/malaria-symptoms

http://www.defense.gov/news/newsarticle.aspx?id=122119

http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2014/04/140423095158.htm