My issue brief is as follows: note that I haven’t fully completed the Chicago End Notes.

Introduction:

Imagine this: two car accidents occur in Pennsylvania, one being in Allegheny County and the other in Butler County. Though these counties are right next to each other, Allegheny County has five trauma centers while Butler County has none. (1) While one victim is transported to their nearest trauma center in under an hour, the other victim is only halfway there. In other words, the victim in Allegheny can receive quality care while the other is still in transit, in life-threatening condition. At this point, Emergency Medical Services (EMS) has a difficult decision to make: to either divert the ambulance to a closer hospital that isn’t an accredited trauma center, or to wait another hour until arriving in Allegheny County. If the patient is taken to a closer hospital, they will likely receive lesser-quality care, but if they wait to receive better care, they risk being too late. In both situations, the victim from Butler County has an undoubtedly worse health outcome.

This phenomenon, known as health disparity, is defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as a preventable difference in healthcare outcomes, often due to lesser opportunities for quality care faced by socially disadvantaged populations (2). Many social determinants of health occur in rural Pennsylvania, from a lack of health insurance and education and the persistence of substance abuse. Because nearly 14% of Pennsylvania’s population lives in rural counties, the state of Pennsylvania’s Health is marked by disparities, especially for its elderly and minority populations (3).

Due to socioeconomic constraints that have led to a lack of resources in rural communities, rural Pennsylvanians are deprived of the quality health care that their urban counterparts receive.

While no solution can build as many hospitals as possible or alleviate the socioeconomic injustices of rural counties, there are small steps that can be taken, one of which is building health clinics. By providing a smaller-scale yet consistent and accessible form of care, these clinics begin to alleviate the health burdens that contribute to larger-scale health outcomes, all while involving the community to increase its educated population across all races. To advocate for this policy, this report will first establish how the conditions of education, financial status, race and ethnicity, and substance abuse had lead to poor health outcomes. I will then explain how building smaller-scale health clinics can provide educational and financial growth that will pave the way for better health resources in rural Pennsylvania counties.

Impacts of Poor Health Access

22% of Pennsylvania residents live in areas deemed Health Professional Shortage Areas by the federal government (6). 26% of these people are rural Pennsylvanian’s while only 1.7% are urban residents (6). This means limited access to primary, secondary, and emergency care, marked by higher transit times. A lack of primary and secondary care means an unhealthier population, and a lack of emergency care means higher mortality. Because transit time to a trauma center is almost 200% higher in rural counties, mortality from traumatic injuries is 40% higher in rural counties (6). Access to primary and secondary care is more complicated, as its impacts vary across ages.

Elder Abuse and Neglect: Delay of Care

Pennsylvania is the 6th oldest state in America (6). If you look at the next two infographics, however, it is clear that this effect is amplified in rural counties. Whereas Pennsylvania as a whole has 7.06% of its residents at 60-64 years old, Butler county’s percentage is 7.87 (7).

Neilsberg: Pennsylvania Population Pyramid

Neilsberg: Butler County, Pennsylvania Population Pyramid

Accordingly, it is paramount that healthcare account for this. Unfortunately, any corrective measures that were made have not reached rural communities. Because rural Pennsylvania has its healthcare facilities much more spread out, this makes it difficult for elderly populations to access, as they may not have the means or ability to travel for appointments. This leads to untreated and undiagnosed conditions, along with what is known as a delay of care. When elderly patients (and patients of any other age) don’t engage in regulatory health visits, the health care that they do require is often emergent, increasing the risk of poor health outcomes. In counties with a lack of trauma centers and the like, elderly people in rural counties are at an even higher risk of poor health outcomes. A lack of healthcare maintenance also leads to more placements in nursing homes, where patients experience lower physical and mental qualities of life (6).

Infant Mortality: Maternal Deserts

With the theme of delayed access to care also comes prenatal care. 1% of children born in rural counties do not receive prenatal care (6). More concerning is that 41% of infants are born to mothers receiving WIC services, a form of supplementary nutrition offered in Pennsylvania (6). These statistics demonstrate the interrelatedness of rural pregnancies and poverty. When pregnant women are members of a lower socioeconomic class, the outcomes are never as good as their wealthier counterparts’. This results in a lack of nutrition and adequate healthcare.

In the case of rural mothers, inadequate healthcare also includes a lack of nearby obstetricians. For a mother who’s dependent on her or partner’s job cannot afford to travel to appointments for extended periods of time. What’s more, the economics of rural Pennsylvania have facilitated “maternal deserts”, or a lack of obstetricians and labor and delivery units (8). Due to financial pressures, rural Pennsylvania hospitals have chosen not to offer OB/GYN or labor and delivery, as it is more advantageous for them to specialize in one form of care. Therefore, without an upheaval of Pennsylvania’s healthcare system, maternal deserts will continue to persist.

What Defines a Rural Community?

The map below depicts the distribution of rural and urban counties in Pennsylvania, with blue counties being rural and green counties being urban (4). As you can see, rural counties make up nearly 75% of Pennsylvania’s land (5). The average Rural Pennsylvanian, is white and older, with 9% of Rural Pennsylvanians being non-white and 46% being 65 or older (6). Along with being an elderly population that is more prone to health problems, these Pennsylvanians face lower household incomes and rates of insurance, along with little of the population having a bachelor’s degree or higher.

PA Office of Rural Health: Rural and Urban Counties in Pennsylvania

Education and Economy

Only 20% of rural Pennsylvania residents have a bachelor’s degree or higher, and 12% do not have a high school diploma (6). This leads to a phenomenon called “brain drain”, where those who do receive higher degrees move to urban areas, allowing rural Pennsylvania lacking of resources and infrastructure. In other words, this perpetuates a higher educational status in urban counties.

In terms of the financial status of rural Pennsylvanians, the average household income is $15,442 less than that of the urban average (6). Additionally, the poverty rate is 1.1% higher in rural Pennsylvania than urban Pennsylvania (1).

Drug Usage

Additionally, drug usage is on the rise, with Pennsylvania having the 8th highest number of overdose deaths in the country, with over half of drug-related deaths being from heroin (6). The outlook in rural Pennsylvania is even worse, making drug usage another hallmark of health in rural Pennsylvania. In 2014 out of the top 20 Pennsylvania counties ranked by increases in drug-related deaths, 14 of them were rural (6).

How Socioeconomic Status Impacts Health Access

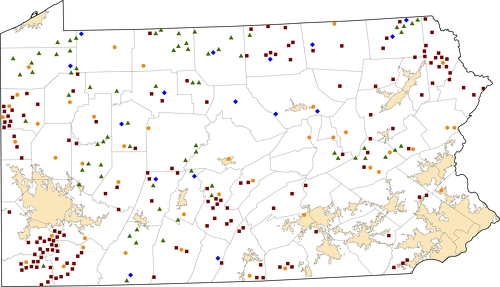

A lack of income entering rural counties makes it extremely difficult for commerically-designed hospitals to operate. Because of this, 2014 saw the greatest amount of rural hospital closures than all of the 15 prior years combined (6). Accordingly, this outlook on rural hospitals is very unattractive to new physicians, especially primary care providers. 2/3 of Pennsylvania primary care physicians practice in rural counties, and 30% of those practicing in rural counties plan to transfer in five years or less. Thus, it is financially impossible for rural counties to have enough healthcare facilities. As you can see below in this map of rural counties, there are only 154 Federally Qualified Health Centers, shown in red and 16 Critical Access Hospitals, shown in blue. The rest of the icons represent short-term or outpatient facilities.

Rural Health Information Hub, Pennsylvania Rural Healthcare Facilities

Healthcare Clinics in Rural Communities

Now that it’s clear that building more qualified or critical access hospitals isn’t possible, it’s time to literally and figuratively fill in the gaps on this map with more health clinics and short-term hospitals. This would be the best way to minimize costs and maximize benefit. By offering primary care and prenatal services, health clinics would alleviate the problem of far transit times, increasing rates of prenatal care and the health of elderly residents. Though clinics cannot provide emergency services, they can be extremely successful in preventing the need for them, by ensuring that rural residents receive proper and regularly-schedule care.

Conclusion:

Due to socioeconomic constraints in the economy and employment rural Pennsylvanians are deprived of the quality health care that their urban counterparts receive, with elderly and infant populations being disproportionately affected. By building up the community, these clinics would lead to more economic revenue, encouraging higher-educated people to stay in their counties. Though these clinics would begin as a small change, it’s important to remember that any change that can prevent someone’s death because of where they live is worth paying for.

1: https://www.ptsf.org/trauma-center/

2: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/disparities/index.htm

3: https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/states/pennsylvania

4: https://www.paahec.org/he-in-pa

5: https://stategovernment.pasenategop.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/30/2021/05/CRP-Rural-Demographics-May-2021.pdf

6: https://www.porh.psu.edu/about/about-rural-health/#:~:text=Health%20and%20Economic%20Challenges%20in%20Rural%20Pennsylvania&text=On%20average%2C%20residents%20are%20older,on%20urban%20and%20rural%20residents.

7: https://www.neilsberg.com/insights/pennsylvania-population-by-age/

8: https://www.porh.psu.edu/pregnant-women-in-rural-pennsylvania-face-expanding-maternity-deserts-heres-why/