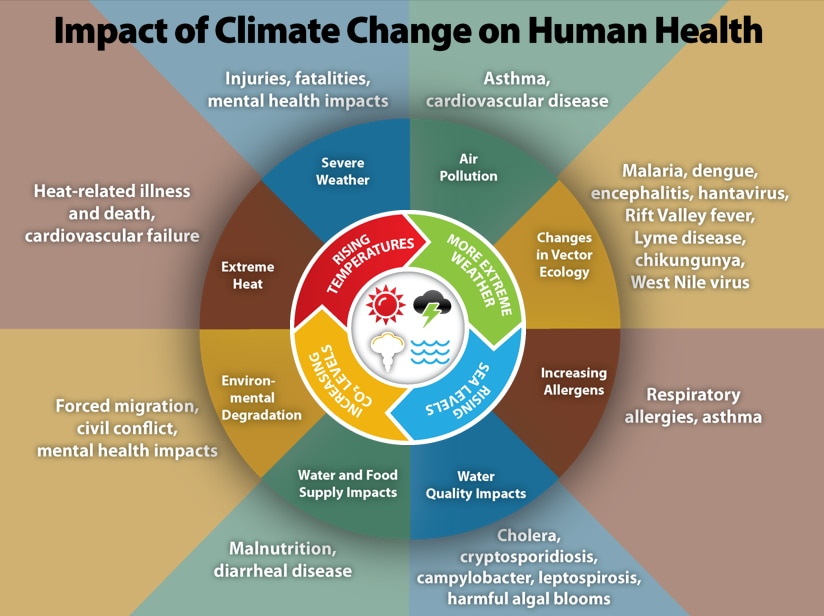

Unjust trends in environmental policy have not only failed to account for minority communities but also purposefully target low-income African Americans, forcing them to live in close proximity to hazardous waste plants and other areas with low air quality. As a result, black communities are profoundly affected by toxins and other pollutants, which, in turn, cause long-lasting health problems and even fatalities. Statistically speaking, “people of color bear a disproportionate share of environmental health hazards” (Milner & Turner, 1999). Evidence of this can be seen in a 2020 study that found that African Americans are 20% more likely to have asthma than whites (Sze, 2020). This is similarly proven by extensive research which has demonstrated that “childhood lead exposure can cause lifelong and very serious developmental, cognitive, medical, and psychological issues” (Turner, 2016). Both statistics amplify the physical and mental burdens greatly taken on by the Black community.

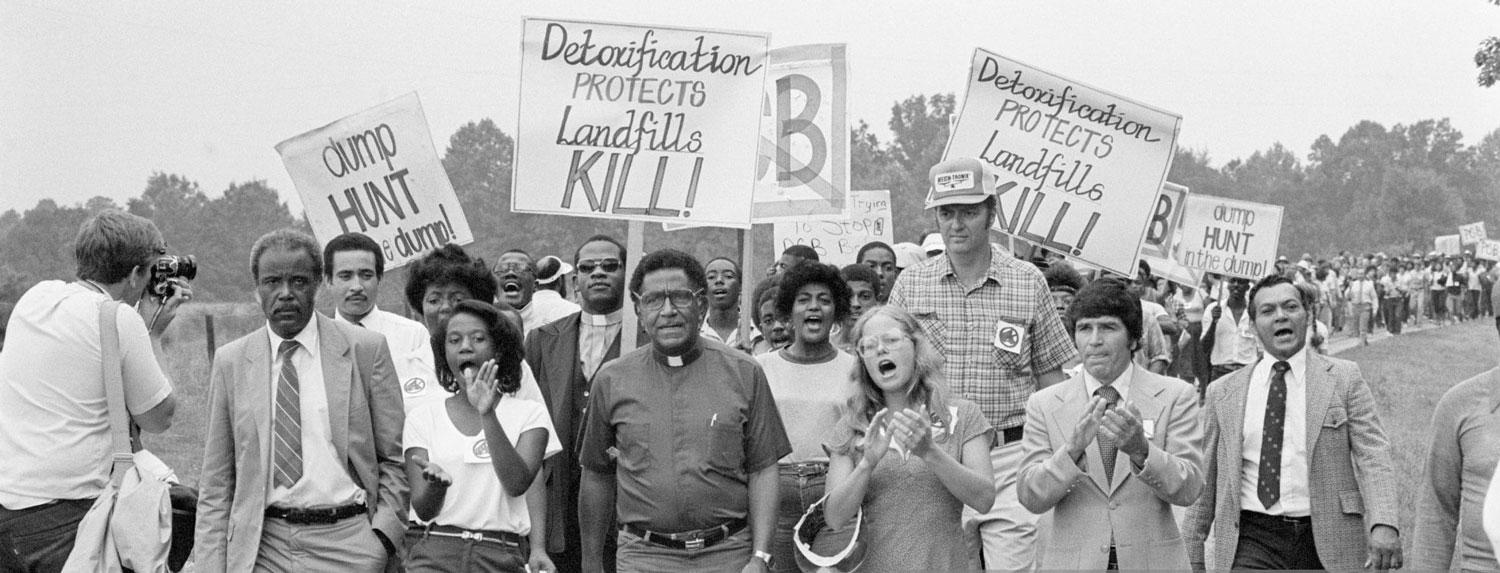

In my senior year of high school I was given the opportunity to interview Samuel Stopler, an environmental and energy economist and professor at the University of Michigan, on the topic of environmental racism and environmental justice. His biggest takeaway was that when acknowledging the impacts of environmental racism, it is “equally important to recognize mental health… [and that] the psychological burden of living in the shadow of a smokestack is something real and something that has effects of its own” (Stopler, 2020). African Americans are not only prone to physical burdens associated with environmental racism but long-lasting and exhausting mental effects as well. These impacts are even further ignored as they often can’t be quantified to statistical data points. Because of this, both local and federal governments are continuing to get away with harmful practices as they fail to implement policies that uphold the standards of environmental justice. If we want to see change, it is important now more than ever, that we as citizens rise up and take action.

So what exactly are these standards you may ask. According to Webster’s Dictionary, environmental justice is the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income, with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies. Paul Mohai, environmental justice professor at the University of Michigan and member of the National Environmental Justice Advisory Council to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, puts this definition in context by stating that “environmental justice affirms the sacredness of Mother Earth, ecological unity and the interdependence of all species, and the right to be free from ecological destruction” (2018). Often, the mistreatment of the natural environment coincides with the susceptibility of minority communities. For instance, big waste facilities release their toxic chemicals into runoff, which eventually ends up in local water sources. Not only do these toxins harm animal and plant life in the aquatic ecosystem, but they poison the drinking water. More often than not, these waste facilities are located in poor black communities that are forced to get their water from toxic supplies.

This is not a newfound issue but rather one that has been going on for decades. In fact, in 1987, a quantitative national-level study was conducted to analyze the demographics of communities surrounding hazardous waste sites. The results reported that “the percentage of people of color in communities containing a commercial hazardous waste facility was double that of communities not containing such facilities. The percentage of people of color in communities containing two or more such facilities was triple” (Mohai, 2018). This research proves that the government purposefully places these dangerous facilities in minority communities because they are seen as the path of least resistance. So, not only must these black communities deal with the health consequences of living near an environmental hazard, but they are also prone to years of ingrained racism that continually puts them at risk.

Sources:

Milner, J. E., & Turner, J. (1999). Environmental Justice. Natural Resources & Environment,

13(3), 478-482. Retrieved October 04, 2020, from https://www.jstor.org/stable/40923860

Sze, J. (2020). Environmental Justice in a Moment of Danger. Oakland, CA: Julie Sze.

Turner, R. (2016). The Slow Poisoning of Black Bodies: A Lesson in Environmental Racism and

Hidden Violence. Meridians, 15(1), 189-204. Retrieved October 12, 2020, from

https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2979/meridians.15.1.10

Mohai, P. (2018). Environmental Justice and the Flint Water Crisis Michigan Sociological

Review,

This is honestly such an important to talk about. I actually have just been listening to podcasts and reading about environmental racism for another class and you hit all the points on the head. Racism and climate change are so much more intertwined than people realize. My favorite point is about how environmental justice requires the involvement of people of all races who are then supposed to equally reap the benefits but how do we expect minorities to help make strides for the environment when they’re still trying to gain respect and their own voice?

I love that you included a direct quote from an expert on this topic that you interviewed yourself. This is also a really interesting subject that I don’t think gets the attention that it deserves. I definitely did not realize that the percentage of waste facilities located in poor, mostly black communities was so high. The long-term effects that this must have on people’s health and overall quality of life has to be staggering. I know that the clean water crisis is an ongoing issue in many predominantly black communities, like in Flint, Michigan where they have not had clean water in years. The ongoing racism in our country is staggering, and it is really interesting to look at it from the context of environmental injustices.