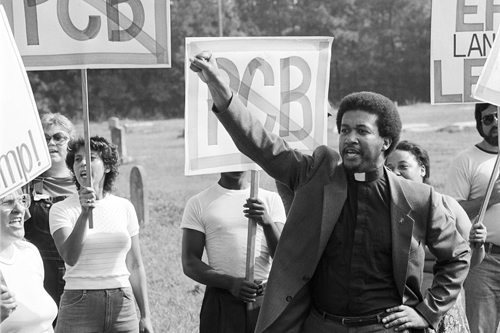

The biggest examples of environmental justice failures can be seen during the process of community development nationwide. In specific, the case of Warren County (one of the original instances that brought the EJ movement to the mainstream) shows how outside governance has failed a specific community. Warren County, North Carolina has a population that is 60% African American and where 25% live under the poverty line. When deciding where to place an environmentally destructive landfill site, Warren County was chosen over a more adequately fit white neighborhood. Thus, community members were forced to bear the adverse health effects of the site, harming them both physically and mentally. With the state given all the power to this decision, it was evident that these higher levels of government officials were making decisions for local populations. These populations being ones that were not granted an adequate voice in the decision-making process or a respected voice in the area in general. When communities, especially minority communities, are pushed away from this very important decision-making process, the end result usually ends up being one that does more harm than good to a particular neighborhood. Those who are bargaining and making decisions on behalf of the victims are far removed from the physical situation and will never have to endure the consequences of pollution firsthand. This distance gives outside officials the motive to put minority communities at high-risk time and time again.

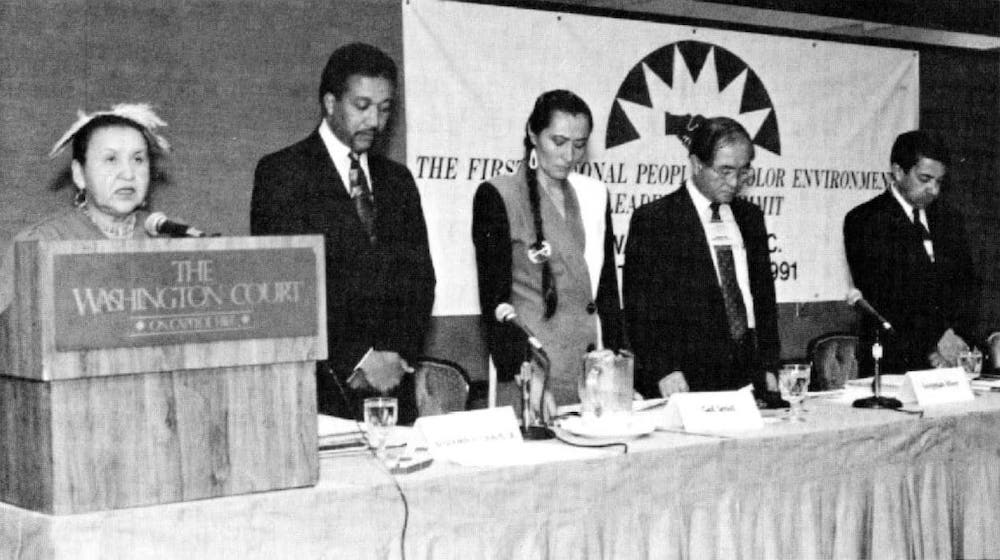

The scenario above demonstrates one of the three most important types of justice, procedural justice. According to New Castle University, procedural justice is defined as “the opportunity for all people regardless of race, ethnicity, income, national origin or educational level to have meaningful involvement in environmental decision-making”. It is evident that the decision-making process was what led to the uneven distribution of environmental hazards. Clearly, higher-ups should not be given such large discretion to communities in which they are so far removed without having input from community members themselves. Furthermore, it is imperative that local governments create a partnership between educated state officials and longstanding community members in order to foster development that is obtainable and appreciated within that specific community. It is important that government officials recognize community development as a living process where inclusion is the very foundation of the process and participation is monitored and maintained throughout. Community members should not be viewed as the subjects of community development by government officials, but rather treated as equals, who play a critical role in a community’s evolution.