Most people our age have grown up hearing about greenhouse gases and their effects on the environment, how they contribute to the changes in climate that we’re seeing around us. While greenhouse gases may seem like a new development, the reality is that we’ve known about their presence for a while. This leads to the question: “who discovered greenhouse gases?”

A quick google will tell you that John Tyndall, an Irish physicist, discovered and set our foundational understanding of greenhouse gases, and throughout much of history this achievement was accredited to him. In actuality however, Eunice Foote, an American climate scientist performed the experiments that proved the existence of greenhouse gases.

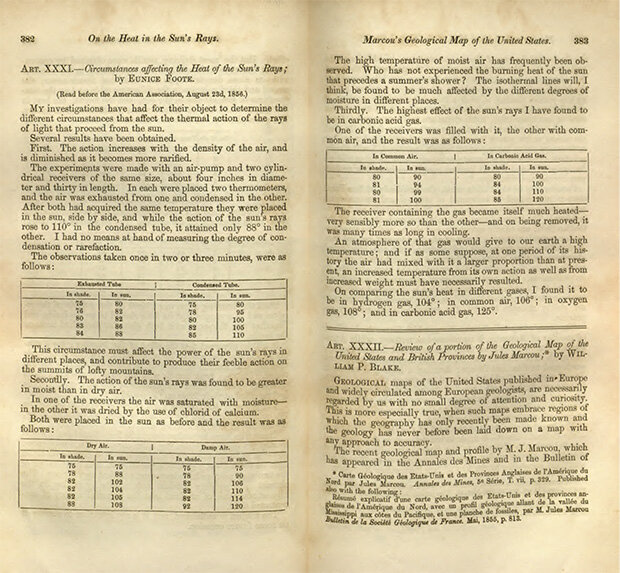

Eunice Foote was a pioneer in her field. She performed experiments in the 1850s that demonstrated the ability of atmospheric water vapor and carbon dioxide to have an effect on solar heating. Her experiments foreshadowed John Tyndall’s later experiments that illustrated the workings of Earth’s greenhouse effect — she beat him by at least three years!

Despite her incredible contributes and remarkable insight into the influence of raised CO2 levels on the Earth’s temperature, she went forgotten in the history of climate scientists until very recently.

Foote utilized glass cylinders, each encasing a mercury thermometer, and found that the heating effect of the sun was greater in moist air than dry air, and that it was highest in a cylinder containing CO2. While her experimental design was simple and didn’t give to much insight into the exact nature of how things worked, Foote was still able to draw remarkable insight from her studies, writing in 1856:

“An atmosphere of that gas would give to our earth a high temperature; and if as some suppose, at once a period of its history the air had mixed with it a larger proportion than present, an increased temperature…must necessarily resulted.”

Her findings were presented in August of 1856 at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) by a male colleague, Joseph Henry. Her paper, nor Henry’s presentation of it, were included in the proceedings of the conference however.

A summary of her work was published in the 1857 volume of Annual of Scientific Discovery by David A.Wells. When reporting on the meeting, Wells wrote: “Prof. Henry then read a paper by Mrs. Eunice Foote, prefacing it with a few words, to the effect that science was of no country and of no sex. The sphere of a woman embraces not only the beautiful and the useful, but the true.”

Her work was later used in a column of the September 1856 issue of the Scientific American to counter the held sentiment that “women do not possess the strength of mind necessary for scientific investigation.” The writer highlighted that her experiments were direct evidence to the contrary: “ the experiments of Mrs.Foote afford abundant evidence of the ability of woman to investigate any subject with originality and precision.”

While much has changed since the time of Eunice Foote, there is still much work to be done to acknowledge the past contributions of women scientists and ensure that future efforts do not go unseen.