Today I would like to take some time to explore the premise of Contingency Theory and how it relates to real-world situations. Prior to taking this course, I have spent a good amount of time studying situational leadership as a participant in many classrooms. I have participated in work trainings, read books, and counseled other leaders on the topic of Situational Leadership, but was surprised to learn that Situational Leadership had an “opposite” in Contingency Theory and didn’t know much about it. Having been a student of Situational Leadership and using that knowledge in my work daily is what is driving my desire to learn more about how Contingency Theory can be applied in real-world setting, and I hope to explore that in this post.

As we learned in our lesson this week, Fiedler’s Contingency Model states that “Fiedler’s contingency model recognizes that leaders have general behavioral tendencies and specifies situations where certain leaders may be more effective than others.” (PSUWC, 2020, L.6) In essence, the model posits that leadership qualities are pretty set once a leader has matured. While we can continue to learn and grow in some regards, the core pieces of a leaders personalities are set after a certain point. The theory recommends that in order to get the best results, you match the leader to the situation. This idea differs from the Situational Leadership model in that the Situational Leadership model recommends that a leader adjust their style based on the situation. (PSUWC, 2020, L.6) While there are merits to both ideas, when applying these premises to real-world situations, I wondered which style might be more practical.

In order to apply the Contingency Theory, one must address the steps to understanding how to classify the work environment. The first step in this process is to determine what the variables of your situation are. We would begin by applying the “Least Preferred Co-worker Scale” to the situation. In this step, the leader answers questions about the team members that they have the hardest time working with. Their answers to these questions provide a determination as to whether the leader has a focus on tasks or people. There are three possible options. Leaders who will focus on tasks first and people second (scored lower on the scale), leaders who will focus on people first and tasks second (scored higher on the scale), and last people who scored in the middle and could focus on either area first. (Flinsch-Rodriguez, 2010) In my opinion, this is the first hurdle that the idea of a Contingency model faces. At a time when we are incredibly concerned with the experience of our people in the workforce, I couldn’t imagine a scenario where a leader was presented with a test and asked to rate the team member that they least prefer to interact with. While the exercise might not call out a specific team member directly, putting a test like this into practice would likely not support positive morale in the organization. There are other issues with the “LPC” as well. “The instructions on the LPC scale are not clear; they do not fully explain how the respondent is to select his or her least preferred coworker. Some respondents may get confused between their least like coworker and their least preferred coworker.” (Northouse, 2007) The tool is not specific in how one should determine their ratings, or specific enough on what the ratings may mean.

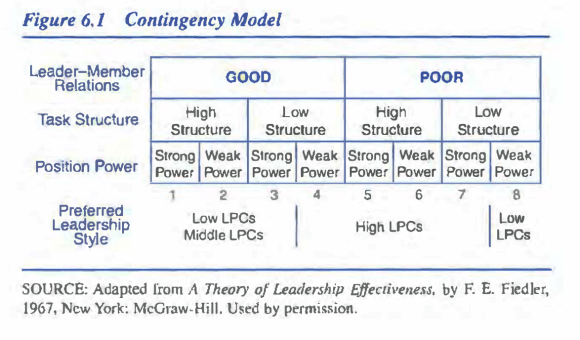

The next step in the process involves a concept called situational favorability. This concept determines how much control the leader has over a situation. From the leader’s perspective, the more control that they have the more favorable the situation. (PSUWC, 2020, L.6) Control in this context is measured by leader-member relations, task structure, and position power. Of these three measures, leader-member relations is the strongest measure of situational favorability. (PSUWC, 2020, L.6) This is where I believe a second hurdle comes in for the overall process. Measuring leader-member relations can take some time, dependent on the size of the organization. You may believe that the team is feeling a certain way, only to uncover through surveys or interviews that there is an issue that you didn’t know about. Constantly assessing and grading these situations are time consuming and would interrupt the typical flow of the operation. After determining the status of the leader-member relations, we would next look at task structure. Task structure measures how hands-on a leader needs to be in order to complete a task. (Flinsch-Rodriguez, 2010) An example of a task that is highly structured, would be changing the oil at a local Lube & Tune. There is a set process, with multiple check points, and a very clear end result. A task that has low task structure would be welcoming customers in the store. There are many ways to welcome a customer, different things that could be said, and the end goal would still be achieved. Last in this step, we would need address the position power of the leader. Do they have sway in the organization? Can they affect change such as hiring decisions, wage adjustments, or annual reviews?

Once you have determined the situational favorability, you can then apply the results from the LPC and start making recommendations about situations that a leader would be a best fit for. Shown below is a figure that represents placement in the Contingency model.

(Northouse, 2007)

One of the main criticisms of the Contingency Model is that “it fails to explain fully why people with certain leadership styles are more effective in some situations rather than others.” (Northouse, 2007) There is no clear reason that task-motivated leaders may be better in tougher situations, as opposed the people-motivated leaders. Conversely, people-motivated leaders tend to fair better in good environments. This is where the third obstacle in the practical use of this theory comes into play. More often than not, a leader has to deal with the situations as they arise. Organizations don’t have the luxury of selecting a specific type of leader based on what is in front of them for the day. In my opinion, this makes the application of this model very tough. I think that there is a benefit in using the model to select an initial assignment for a leader. For example, you could select a task-motivated leader for an assignment in a department that is struggling, in order to help turn it around. The question becomes though, what is the longevity of using this model to keep making decisions? Do you keep swapping leaders in and out of positions based on the needs of that moment, and is that sustainable? In my opinion, it is not sustainable.

As a real world example, I would share an experience that I had while working for a global restaurant company. There was a time when I was faced with taking over a restaurant that was in very poor shape. As a leader who would have scored lower on the LPC scale at that time and who would have had good team member relations, as a new manager in the setting, high task structure, and strong position power, I was well-placed to take over the restaurant and turn the situation around. As time went on though, and the situation needed more relational leadership as we navigated the waters of a new boss and a newer staff, my fit became poorer and I was less effective in that position. This is where crux of the issue with the model lies. It wouldn’t make sense for my boss to remove me from that situation and replace me with another leader, just because the situation had changed. I had to adapt and figure out what my team needed from me, because that was my responsibility as a leader for the organization.

To answer a question that I posed earlier, I believe that Situational Leadership is a more practical tool to employ as a strategy for While I have been critical of the Contingency Theory model, I do believe that there is real benefit to using the model as a tool to consider the strengths and weaknesses of a leader relative to the situation that they are faced with. The utilization of the theory is seems cumbersome, but I think that at the root of the method there is sound data and much that can be learned from matching a leader to a situation that they are the most skilled to handle. I feel that this theory is helpful in the initial decision making process of where to place talent, but also as a way to understand why talent may or may not be doing well in their current role. “It can be used to explain why a person is ineffective in a particular position even though the person is a conscientious, loyal, and hard-working manager. Also, the theory can be used to predict whether a person who has worked well in one position in an organization will be equally effective if moved into a quite different position in the same company.” (Northouse, 2007) It has been proven that there is a lot of benefit to considering the tenants of this model when making decisions around selection and disbursement of talent in an organization, as one of the tools in our tool belt.

References:

Flinsch-Rodriguez, P. (2010, December 27). Contingency Management Theory. Retrieved February 20, 2020, from https://www.business.com/articles/contingency-management-theory/

Northouse, P. G. (2007).Contingency Theory. Leadership: Theory and Practice. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications, Inc. pp.113-126

Pennsylvania State University Work Campus (2020). PSYCH 485. Lesson 6: Contingency & Path-Goal Theories. Retrieved from https://psu.instructure.com/courses/2045005/modules/items/28166610

Sorry forgot my references:

Northouse, P. G. (2007).Contingency Theory. Leadership: Theory and Practice. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications, Inc. pp.113-126

I appreciate how you looked at the two contrasting theories, and tried to place them in a real world situation. I agree with your assessment of situational leadership being more practical. As a person who has been in a leadership position for over 12 years, I consistently find myself managing via the situational approach. Although having contingencies is important, basing your leadership off of a certain situation is more practical. What’s telling to me is that part of the Contingency Theory includes situational variables (Northouse, 2007, p114). I personally think task structure is the most important variable of effective leadership. The other two variables, leader-member relations and position power, are important, but without proper task structure the entire process can fail. (Northouse, 2007, p114). Although the Contingency theory states that “certain styles are effect certain situations” and different leaders are right for different situations, the practicality of this unreachable. The real scenario is that an effective leader must be willing to adapt if the goals of each individual are not the same. Even if they don’t want to change their behavior, a leader must be willing to recognize the different situations and be able to react to them accordingly. It is my belief that situation will always trump contingency based theories.