On January 28, 1986, the space shuttle Challenger exploded seventy-three seconds after lift-off. I was eight-years-old, and like many students around the country, I watched the horrific events unfold from a desk in my classroom. My third grade teacher, Mrs. Porter, had polio as a child and so needed a walker to move around. I remember her struggling to get to the television fast enough to turn it off before we figured out what happened. Kids are intuitive though, we may not have fully understood what we saw, but we knew something went wrong. I recall school closing early that day and watching President Reagan speak to the nation that evening.

Seven astronauts perished, including the first civilian to travel to space, a teacher named Christa McAuliffe. A recently watched a new docuseries about the incident on Netflix. Challenger: The Final Flight chronicles the lead-up and aftermath of the disaster. It has long been known that the explosion resulted from the failure of an o-ring to seal correctly in one of the solid rocket boosters (SRB). However, I was not aware that the faulty leadership ethics of individuals involved with the space shuttle program also contributed to the tragedy.

Like many of the leadership theories we have studied this semester, interest in how ethics plays a role in leadership has grown due to recent corporate and political scandals (Northouse, 2016). Ethics describes the values, morals, and motives of individuals that society deems acceptable and, consequently, we utilize to guide our decision-making (Northouse, 2016). Ethics in leadership is how leaders inform their decisions, what they do, and who they are (Northouse, 2016).

A year before the Challenger explosion, in January 1985, an engineer from the contractor responsible for the SRBs, Morton Thiokol (MT), identified an issue with the o-rings (Boisjoly, Curtis, & Mellican, 1989). Roger Boisjoly was a senior scientist with MT. At the time, he had twenty-five years of experience in the aerospace industry and was the leading expert in the United States on o-rings and rocket joint seals (Boisjoly et al., 1989). Boisjoly reported his findings to MT superiors and NASA engineers, to no avail, so he ran further laboratory tests that provided more evidence supporting his claim (Boisjoly et al., 1989). Then, a post-flight SRB inspection in April 1985 revealed operational field evidence of o-ring resiliency problems, heightening concern among MT engineers (Boisjoly et al., 1989).

Boisjoly and colleagues from MT presented their case to NASA engineers and leaders in July 1985. MT formed a Seal Erosion Task Force; however, Boisjoly quickly became frustrated when the team did not progress (Boisjoly et al., 1989). Of the 2500 MT engineers assigned to the space shuttle program, MT executives assigned five to the task force (Boisjoly et al., 1989). Boisjoly sent an official company memo to MT Vice President of Engineering, Bob Lund, in which he stated that if erosion of the seal happened during an operational flight, “The result would be a catastrophe of the highest order – loss of human life” (Boisjoly, July, 1985a as cited in Boisjoly et al., 1989, p. 220).

NASA allowed Boisjoly to present an overview of the joint and seal configuration to 130 technical experts at a conference in October 1985, with strict guidance not to express the situation’s critical urgency (Boisjoly et al., 1989). Boisjoly hoped to solicit suggestions from the technical experts, but nothing came to fruition. On the 30th, Challenger launched without catastrophe, but not entirely without incident. While seal erosion did not occur, there was evidence of the conditions that cause the erosion – hot gas blow-by (Boisjoly et al., 1989). Boisjoly determined that this was because of a temperature difference. The seal’s ambient temperature on October 30 was 75 degrees, and the seal failed for 2.4 seconds (Boisjoly et al., 1989). However, on previous tests at 50 degrees, the seal failed for 10 minutes, at which time the hot gas blow-by caused the potentially catastrophic seal erosion (Boisjoly et al., 1989). Boisjoly and other MT engineers viewed this as evidence that the o-ring was not stable at low temperatures (Boisjoly et al., 1989). However, to their dismay, NASA and MT leaders and some NASA engineers instead decided this meant that Boisjoly’s claims were inconclusive (Boisjoly et al., 1989).

The dark side of leadership is unethical and destructive (Northouse, 2016). Padilla, Hogan, and Kaiser (2007) developed the toxic triangle (figure 1) as a means to depict how destructive leaders, susceptible followers, and conducive environments influence each other and how their connection leads to damaging and unethical behaviors (Northouse, 2016). Details revealed in the investigation after the explosion made it clear that NASA and MT had spent [at least] the previous year living on a toxic triangle of unethical, destructive leadership behaviors and systemic environmental issues within their organizations. While many incidents leading up to the Challenger disaster bear witness to pervasive unethical and destructive behavior at both NASA and MT, it is most grossly apparent in a three-way teleconference that took place on January 27, 1986 – the night before the launch.

It was eighteen degrees at Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral, Florida, where the Challenger sat on a launchpad. There was concern about low overnight temperatures. A three-way teleconference between MT Wasatch Operations in Utah, NASA’s Kennedy Space Center, and NASA’s Marshall Flight Space Center in Alabama convened. As leaders and engineers from two of the nation’s premier science and engineering institutes gathered over the phone, tensions were high.

MT Vice President of Space Booster Programs, Joe Kilminster, started the call, immediately turning it over to MT engineers, namely Boisjoly. He presents thirteen charts detailing a year’s worth of findings regarding the instability of the o-ring (Boisjoly et al., 1989). Due to the predicted low temperature overnight, the risk that the o-ring would fail to seal for an extended period of time, allowing hot gas blow-by to cause severe erosion of the o-ring was significant. If erosion occurred, it would cause the ultimate catastrophe, thus he recommends against launching (Boisjoly et al., 1989). Bob Lund, Vice President of Engineering for MT, closes out their portion of the call with a final chart that states the ambient temperature with wind must be such that seal temperature would be greater than 53 degrees (Boisjoly et al., 1989). Since the overnight low at Kennedy Space Center was 18 degrees, MT recommends [again] against lunch on January 28, 1986, or until the seal temperature exceeds 53 degrees (Boisjoly et al., 1989).

Larry Mulloy, NASA Booster Project Manager, Kennedy Space Center, ignores Lund and asks Kilminster for his reaction (Boisjoly et al., 1989). Kilminster says he supports his engineers’ position and recommends against launch below 53 degrees (Boisjoly et al., 1989). MT has now recommended AGAINST launching three times. In this teleconference, Larry Mulloy displays destructive and unethical leadership behavior. He is not tolerant of oposing points of view, he is not thinking of the welfare of others, and he distorts the information MT presents such that it is counterproductive (Northouse, 2016). Mulloy’s tone and treatment of those participating in the teleconference sets the ethical climate as one where the only correct opinion is his (Northouse, 2016). After the investigation, many people would blame him for the tragedy. He presents a cold and withdrawn demeanor in the docuseries and states that he blames himself for the explosion, but that he does so without guilt (Junge & Leckart, 2020, S. 1 E. 4).

NASA Deputy Director of Science and Engineering, Marshall Flight Space Center, George Hardy, speaks-up and says he is “appalled” by MT’s recommendation, BUT, he will not go against the contractor’s recommendation (Boisjoly et al., 1989). Hardy appears to fill the role of a conformer on the toxic triangle. Conformers follow the leader to feel more important and satisfy unmet needs (Northouse, 2016). He somewhat goes along with Mulloy’s destructive behavior but does not fully commit. It is as if he is trying to ‘ride both sides of the fence,’ if you will. He is trying to maintain a sense of neutrality so no matter what happens he is clear of wrongdoing.

Stanley Reinartz, Manager of the Shuttle Project Office, Marshall Flight Space Center, also chimes in with an objection, stating that solid rocket motors are qualified to operate between 40 and 90 degrees (Boisjoly et al., 1989). Reinartz is a colluder. Colluders are ambitious, they take the leader’s side because they desire status and view it as an opportunity to get ahead (Northouse, 2016). He sees Mulloy’s ambition to launch and ascribes to the same NASA beliefs and values (Northouse, 2016).

Mulloy retakes the floor, citing the ‘inconclusive’ data from previous launches he objects to MT’s recommendation (Boisjoly et al., 1989). He claims MT is attempting to change launch commit criteria the night before a launch, and ‘they’ cannot do that (Boisjoly et al., 1989). This claim is an interesting data point because, during the investigation after the explosion, Mulloy testifies that he did not violate launch commit criteria because o-ring seal temperature is not part of said criteria (Boisjoly et al., 1989). A clear misrepresentation of the truth – destructive and unethical behavior (Northouse, 2016).

“My God, Thiokol, when do you want me to launch, April?!” Mulloy asks in exasperation (Junge & Leckart, 2020, S. 1 E. 3, 22:39). Mulloy recalls that he was angry at MT for what he thought was an irrational decision (Junge & Leckart, 2020, S. 1 E. 3). His phrasing and exasperation are examples of how destructive leaders are attention-getting and use power and coercion to get what they want (Northouse, 2016).

Brian Russell, one of the MT engineers in the room for the teleconference, opines that Mulloy’s comment was arrogant and intimidating and changed the tone of the call (Junge & Leckart, 2020, S. 1 E. 3). MT, receiving billions of dollars from NASA for their contract, was under much pressure. They heard an underlying message in Mulloy’s statement; he wanted them to change their minds and give them the answer he wanted (Junge & Leckart, 2020, S. 1 E. 4).

Boisjoly held his ground and continued recommending against the launch, continued going over his charts, and continued repeating the data that correlated low temperature with seal erosion and the likelihood of catastrophe. He does not gain any ground with NASA. Kilminster requests a five-minute caucus off-net (Boisjoly et al., 1989).

Senior Vice President of Wasatch Operations for MT in Utah, Jerry Mason, begins the caucus. “A management decision is necessary” he says (Boisjoly et al., 1989, p. 221). The engineers’ instincts tell them that an attempt to reverse the no-launch decision is coming (Boisjoly et al., 1989). They again go over their charts and data attempting to reconvince executives of the danger (Boisjoly et al., 1989). The room is silent until Mason asks, “Am I the only one who wants to fly?” (Boisjoly et al., 1989, p. 222). He then surveys only the executives in the room. When he gets to Lund, he [Lund] is visibly torn (Boisjoly et al., 1989). Mason tells him, ‘it’s time to take off your engineering hat and put on your management hat’ (Boisjoly et al., 1989).

During the MT caucus, Mason is a destructive leader. By starting the discussion with the statement ‘we need a management decision,’ he uses intimidation to let his followers know they need to discard their values and ignore their intuition. This is an example of using power and coercion (Northouse, 2016). When he instructs Lund to take off his engineering hat, he shows a complete lack of integrity and plays to Lund’s basest fears (Northouse, 2016). Mason’s only concern is pleasing NASA. He wants his managers to fall in line regardless of their apprehensions, showing a reckless disregard for his actions (Northouse, 2016). Feeling the pressure, Lund and Kilminster ultimately conform to their destructive leader’s unethical behavior.

The four MT leaders vote unanimously to recommend Challenger’s launch. They exclude all others from the decision. The teleconference reconvenes with Kennedy Space Center, and the four MT leaders present new, mostly irrelevant data to support their new position (Boisjoly et al., 1989). Kilminster states, “Even though the low temperatures are concerning, we have reassessed the data and have concluded that it is inconclusive” (Junge & Leckart, 2020, S. 1 E. 3, 25:15).

NASA fully accepts MT’s reassessment without question; however, they ask Kilminster to put it in writing, sign it, and fax it to Kennedy Space Center (Junge & Leckart, 2020, S. 1 E. 3). Kilminster complies.

Brian Russell tearfully recalls, “I knew how to run the fax machine, and I’m the one who sent it down. That’s the time that I wish – I wish so badly that I’d have just said, ‘There’s a dissenting view here.’ Just to let them know that this wasn’t a unanimous decision, but that there was at least one person, if not many, who believed we should stick with the original recommendation” (Junge & Leckart, 2020, S.1 E. 3, 26:17).

Boisjoly returned to his office and made the following journal entry:

I sincerely hope this launch does not result in a catastrophe. I personally do not agree with some of the statements made in Joe Kilminster’s written summary stating that SRM-25 is okay to fly (Boisjoly, 1987 as cited in Boisjoly et al., 1989, p. 223).

At 11:38 a.m. the next day, the space shuttle lifts-off. There are 500 people in the viewing stands, including family members, school children, and a girl scout troop that raised over two thousand dollars to be there (Junge & Leckart, 2020, S. 1 E. 3). Millions of people are watching on television, including me. For seventy-two seconds, we marveled at this machine operating at the very limit of human engineering. Then, the celebrations, now quiet, turned to confusion and despair.

When you blow up a three billion dollar orbiter and kill seven people on live television, it’s not going to wait two or three months for an investigation (Junge & Leckart, 2020, S.1 E. 4, 19:17).

President Reagan appointed a commission, commonly known as The Roger’s Commission, to investigate the accident, and after six months, they produced a 261-page report. The commission ultimately determined that o-ring seal failure and erosion led to the explosion, just as the MT engineers predicted. They also attributed the accident to a complex NASA organizational structure that produced flawed decision making and miscommunication. Although all of the players referenced above, plus many more from NASA and MT, provided testimony to the commission, they did not implicate any individuals by name.

NASA had a “we can do anything” culture (Junge & Leckart, 2020, S. 1 E. 4, 36:17). Top leaders and mission operators who spent their time behind a desk had the utmost confidence in the space shuttle program even though the engineers and astronauts had concerns – “NASA had a streak of arrogance” (Junge & Leckart, 2020, S. 1 E. 1, 39:48). However, the space shuttle program NASA sold to Congress did not deliver. NASA’s crown jewel was over budget and behind schedule (Junge & Leckart, 2020, S. 1 E. 1). Going into 1986, they promised 16 flights; it would be a challenge, but they promised Congress, so they would make it happen at any cost.

NASA and MT’s complex structures created environments conducive to a destructive leader’s power and coercion. A conducive environment allows a destructive leader to take over because it does not have a solid foundation, is easily manipulated, lacks checks and balances, and has ineffective policies (Northouse, 2016). MT leadership, feeling threatened, succumbed to the vulnerable environment, and gave-in to Mulloy during that fateful teleconference. When followers feel threatened, they often give-in to a destructive leader (Northouse, 2016). NASA’s standard launch protocol was to prove that it was safe to launch, which MT could not do, so the launch should have been postponed. However, because of their arrogance, NASA – by way of Larry Mulloy – manipulated the protocol so that MT instead needed to prove that the launch would fail, which MT could not do either (Boisjoly et al., 1989). MT’s evidence raised enough concern to deem the launch unsafe, but they could not prove with 100% certainty that the launch would fail.

Further supporting NASA’s conducive environment for destructive leaders, the locus of control for space shuttle launches lacked adequate checks and balances (Northouse, 2016). The Challenger launch protocol was not the first protocol bastardized in pursuit of Mulloy’s agenda. NASA had a requirement that a shuttle could not launch if there were a redundant feature issue, which happened when they found erosion in the secondary o-ring after Discovery’s January 1985 launch. It would take a couple of years to address the o-ring issue thoroughly, but Mulloy did not want to ground the entire fleet, so he issued a waiver because he determined there was not enough risk not to fly (Junge & Leckart, 2020, S. 1 E. 4). Mulloy’s reasoning, “We were under tremendous pressure, both schedule and technical. If you don’t keep your schedule, you don’t keep your budget, so I put the pressure on myself, just as a matter of pride” (Junge & Leckart, 2020, S. 1 E. 4, 38:08). However, the waiver states the risk is “Actual loss: loss of mission, vehicle, and crew” (Junge & Leckart, 2020, S. 1 E. 4, 35:20).

What is riskier than the loss of mission, vehicle, and crew? Mulloy was so fixated on keeping a promise to congress, he could not see beyond the schedule. Larry Mulloy, nor anyone at NASA, treated MT’s opinions or decisions with respect; they treated MT as a means to their own end – getting shuttles into space (Beauchamp & Bowie, 1988 as cited in Northouse, 2016).

There is an ethical ambiguity between organizational and individual responsibility (Boisjoly et al., 1989). After the Challenger explosion, NASA leaders blamed their ignorance and fatal decision-making on organizational barriers. Those at NASA and MT who had a role in the Challenger disaster are not bad people, but they did act badly (Junge & Leckart, 2020, S. 1 E. 4). As leaders, we cannot allow lines on a chart to undermine our ethical responsibilities or those of the individuals within our organizations. We cannot defer to the anonymity of procedures. We cannot shield ourselves from consequences with inaction. It is a our responsibility to lead first and foremost through the strength of our character, courage of our convictions, and in accordance with moral conduct. These elements should be the foundation for the policies and structures of the public and private institutions within which we live and work.

Remember, the triangle is a choice. You decide whether or not to be a part of it.

The crew of the space shuttle Challenger honored us by the manner in which they lived their lives. We will never forget them, nor the last time we saw them, this morning, as they prepared for their journey and waved good-bye and ‘slipped the surly bonds of earth’ to ‘touch the face of God.

– President Ronald Reagan

Space Shuttle Challenger Memorial is located near the Memorial Amphitheater in Arlington National Cemetery, June 16, 2015, in Arlington, Va. (U.S. Army photo by Rachel Larue/released)

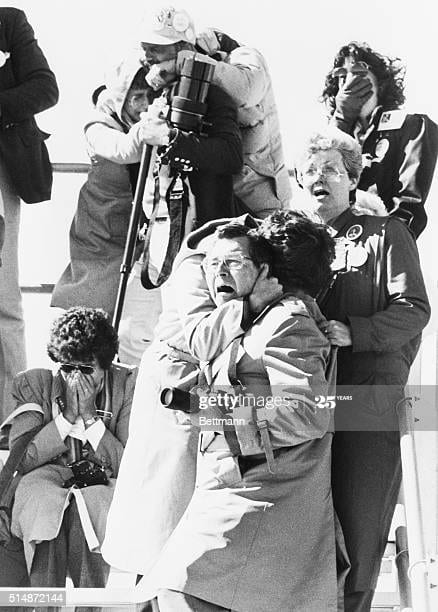

Faces of spectators register horror, shock, and sadness after witnessing the explosion of the Space Shuttle Challenger 73 seconds after liftoff, a disaster in which all seven astronauts aboard died on January 28, 1986. Cape Canaveral, Florida.

Senior class President Carina Dolcino is stunned by the news that the space shuttle carrying Concord High School teacher Christa McAuliffe exploded after launch on Jan. 28, 1986. Students at the school watched the launch on television sets scattered throughout the school. A gala celebration had been planned for a successful launch. (AP Photo/Ken Williams/Concord Monitor)

The family of Christa McAuliffe, a teacher who was America’s first civilian astronaut, react shortly after the liftoff of the Space Shuttle Challanger at the Kennedy Space Center, Tuesday, Jan. 28, 1986. Shown are Christa’s sister, Betsy, front, and parents Grace and Ed Corrigan. (AP Photo/Jim Cole)

References

Boisjoly, R. P., Curtis, E. F., & Mellican, E. (1989). Roger Boisjoly and the Challenger disaster: The ethical dimensions. Journal of Business Ethics, 8(4), 217-230. doi:10.1007/bf00383335

Junge, D. (Director) & Leckart, S. (Director). (2020, September 16). Space for Everyone (Season 1 Episode 1) [Docuseries episode]. Challenger: The Final Flight. Netflix.

Junge, D. (Director) & Leckart, S. (Director). (2020, September 16). HELP! (Season 1 Episode 2) [Docuseries episode]. Challenger: The Final Flight. Netflix.

Junge, D. (Director) & Leckart, S. (Director). (2020, September 16). A Major Malfunction (Season 1 Episode 3) [Docuseries episode]. Challenger: The Final Flight. Netflix.

Junge, D. (Director) & Leckart, S. (Director). (2020, September 16). Nothing Ends Here (Season 1 Episode 4) [Docuseries episode]. Challenger: The Final Flight. Netflix.

Northouse, P. G. (2016). Leadership: Theory in practice (7th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: SAGE.