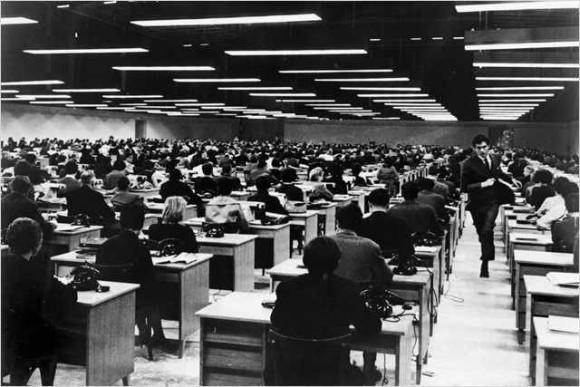

High-rise office buildings are a standard fixture on most city skylines. The sun glistens on their glossy exteriors like a beacon to the gods of business and commerce. To those that have never spent time in one, office buildings illicit images of mahogany board rooms, company presidents making high-pressure decisions, and elevators delivering catered lunches and employees to their “very important” jobs. Behind the gloss and glitz, there are often infinite rows of cubicles – stone colored walls and desks that can be configured into one of a dozen shapes. The occupants of these cubicles are the rank and file of the corporations. Not the faces on the cover of Forbes magazine, but the faces of those that help the company afford the rent in the glass and steel structure the company calls headquarters. The leaders of those companies come in all shapes and styles. The differing styles lead to different outcomes, and some styles should be avoided to prevent failure. The style approach to leadership involves two types of behaviors: task behaviors and relationship behaviors (The Pennsylvania State University, 2015).

High-rise office buildings are a standard fixture on most city skylines. The sun glistens on their glossy exteriors like a beacon to the gods of business and commerce. To those that have never spent time in one, office buildings illicit images of mahogany board rooms, company presidents making high-pressure decisions, and elevators delivering catered lunches and employees to their “very important” jobs. Behind the gloss and glitz, there are often infinite rows of cubicles – stone colored walls and desks that can be configured into one of a dozen shapes. The occupants of these cubicles are the rank and file of the corporations. Not the faces on the cover of Forbes magazine, but the faces of those that help the company afford the rent in the glass and steel structure the company calls headquarters. The leaders of those companies come in all shapes and styles. The differing styles lead to different outcomes, and some styles should be avoided to prevent failure. The style approach to leadership involves two types of behaviors: task behaviors and relationship behaviors (The Pennsylvania State University, 2015).

Leadership styles are about behaviors. Oftentimes, if you ask someone what makes a good leader, they will describe traits of a person: intelligence, confidence, friendliness, assertiveness. Since the 1940’s however, there has been much research done into leadership styles. Three major studies came to conclusions that are still looked at today. Ohio State researchers interviewed subordinates about a series of behaviors that their managers had exhibited. The researchers then compiled the answers and noticed two major trends: 1) the managers exhibited behaviors that focused on task completion, and organization of tasks (Initiating Structure) and 2) the managers exhibited behaviors that were focused on the subordinates themselves, their well-being, and establishing relationships with the subordinates (Consideration) (Northouse, 2013). Interestingly, researchers at The University of Michigan conducted similar research and found similar behavior clusters. They identified them as Employee Orientation and Production Orientation (Northouse, 2013). Later in the 1960’s further research was completed by Blake and Mouton. They elaborated on the research completed years earlier by Ohio State and The University of Michigan and created a grid that assigns points to how much a leader is concerned with the people in their organization and how much a leader is concerned with the production of their organization (Edwards, Rode, & Ayman, 1989).

So, what does all that research mean? According to the style approach, leaders will do well to be mindful of the emphasis they place on task behaviors and people behaviors. I had a manager (actually the owner of the company) who was extremely mindful of how he treated his employees. He made a point of walking the floor each day that he was in the office to personally greet each person by name. This behavior gave a clear indication to each of us that we were valued and appreciated. He was also very savvy. He partnered with a woman who was clearly focused on the task organization and completion of the organization. She understood that the employees needed certain tools to assist them in completing their duties which would then lead to the success of the company. Their self-awareness of their personal styles helped the owners to create a positive atmosphere and successful company. On the other hand, there are certain behaviors that will almost always contribute to the failure of a company.

Researchers have found five self-defeating behaviors that contribute to failure as a leader: inability to build relationships, failure to meet business objectives, inability to lead and build a team, inability to adapt, and inadequate preparation for promotion (The Pennsylvania State University, 2015). Before my current job, I was an occupant of more than one of those aforementioned cubicles. At one point, I worked for a company whose president called the cubicles “corrals”. I can assure you that referring to our desks in the same vernacular that a ranch farmer would use, was no way to endear his subordinates. This most certainly qualifies as a self-defeating behavior that contributed to the failure of his leadership style. A different manager was not successful in leading and building a team. She was young and lacked a certain confidence. As a result, she micromanaged every assignment she delegated, making her subordinates feel useless and unimportant. The department eventually had a major walk-out with employees leaving en masse.

The faceless millions living in cubicle-land each day have a front row seat to leadership styles that run the gamut. Their stories could (and do) fill blog entries and social media posts each and every day. Managers and leaders would do well to pay attention to these posts – both the good and the bad. A manager style adjustment might be just the thing to take their group to the next level – and maybe to another floor of that big, shiny high-rise.

Edwards, J. E., Rode, L. G., & Ayman, R. (1989). The construct validity of scales from four leadership questionnaires. Journal of General Psychology, 116(2), 171-181.

Northouse, P. G. (2013). Leadership Theory and Practice (Sixth ed.). Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

The Pennsylvania State University. (2015). Lesson 5: Style and Situational Approaches; Description of Style Approach. Retrieved from PSYCH485: Leadership in Work Settings: https://courses.worldcampus.psu.edu/su15/psych485/001/content/05_lesson/03_topic/02_page.html