By Fernando Ribeiro

As a child, you are likely to have changed schools a couple of times. If you haven’t, you probably have gone through a similar process at your work environment, at a club you just became member of, or in a new city you have moved in.

Almost every human – and to that matter almost any social animal – knows the stress associated with membership affiliation and the struggle to find a place in a given group. Social support can considerably minimize the impact of a stressor (Sapolsky, 2004), such as a change of jobs, school, or city. Not surprisingly, humans, the social animals described by Aristotle (Gleitman, Gross, & Reisberg, 2011), also face the same stressors while trying to find their place in a group.

Groups are undoubtedly important for humans’ wellbeing. Maslow (1943) proposes that after physiological and security needs are met, humans have a need for belongingness1. Feeling a sense of belonging and acceptance is crucial to fend off loneliness, social anxiety, and even clinical depression (College of the Redwoods, n.d.).

If you accept the theory that groups are so important for human beings, key questions might be hovering around your head right now. What does it take to form a group? What about groups at work? How does leadership impact group formation? How can competition among groups be transformed into cooperation?

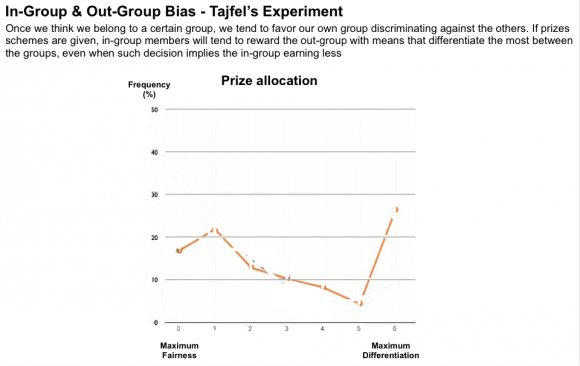

Group formation – and most people would be surprised by that – is as complex as the flipping of a coin. No complex similar traits, similar tastes, or values; groups can be randomly formed by flipping a coin and assigning members to group A and B (Wolfe, 2004; Tajifel, 1970). And once a group is formed, members of the group will tend to favor their own group and discriminate against the other groups, seeking maximum differentiation (Tajifel, 1970).

In-group2 members will let go of higher rewards for their own group if they are given the chance to earn less in a way that better differentiates the two-groups. Rather than, say, earning $1,000 for the in-group and rewarding the out-group with $950, the in-group is more likely to prefer a rewarding system that pays the in-group $400 and the out-group $200 since the latter promotes a clearer differentiation. The dynamic for in-group and out-group has just been created and perpetuated.

If groups can be formed by the flip of a coin, how does this process happen at work? This is the question that Leader-Member Exchange (LMX) tries to address (Northouse, 2013).

Rather than looking at leaders as constant-behavior people in their reaction toward followers, LMX theory accepts that each interaction between a leader and a follower is unique and dependent on the content, personality, involvement, and process of such an exchange; elements that will define the dyadic relationship between leader and follower (Northouse, 2013, Lunenburg, 2010). Based on the quality of such dyadic relationship with individual members, two main groups – guess their names – will be formed: the in-group and the out-group.

Replicating Tajifel’s findings, LMX shows that subordinates in the in-group receive – from the leader – more information, more involvement, more confidence, and influence than does the out-group (Dansereau et al., 1975 as cited in Northouse, 2013).

The problem with in-group and out-group formation is twofold. First confirmation bias (Princeton, n.d.) suggests that people will tend to look at information or data in a way that confirms their preconceptions and hypothesis. Second, the label effect or self-fulfilling prophecy (Rosenthal & Jacob, 1963) might be the driver for the real group formation, i.e. once somebody believes he or she is in this group or that group, this person will act in ways that will eventually lead her to be in this group or that group.

To understand this last proposition, just think of yourself in a classroom or in a work environment. Even if you had just joined the class or just been admitted to your job, you are likely to be constantly scanning the surroundings, trying to categorize the types of people around you as well as the groups. Don’t feel guilty if you do so – it is part of human nature to try to categorize what is going on around us – blame it on cognition and the need for predictability (Sapolsky, 2004; PBS, 2009). Truth is, as soon as you start scanning, you start classifying who is who. There is the teacher’s pet or the boss’s role model; there is the controversial and oppositional student or worker; there is the cool and never-mind guy, there is the always-wrong or to-be-beaten member. As you label each one, you see who is part of the in-group and who is part of the out-group and you try to determine whether you are going to be part of the in-group or the out-group. As you form your opinion about the place you belong to, there is a chance that you start emulating behaviors that are congruent with those of that group. You will look for evidence that confirms that your hypothesis is true and any dubious stimuli coming from leaders or coworkers will be construed according to your belief system. This in turn will help create a self-fulfilling prophecy in which your reality will converge to what you think will happen.

However, looking at this typical situation as either-or, that is, either you are part of the in-group or part of the out-group, gives the false impression that leaders and followers have little to do to change this situation. And this is a major mistake, which brings me to the question on how leadership impacts group formation.

Humans and hence leaders and followers, to start with, are not mere consequences, but rather agents of change. If group formation is as simple as the flip of a coin and maximum differentiation among groups is the norm (Tajifel, 1970), what can we do as leaders or followers to transform maximum differentiation – competition – into cooperativeness?

Sherif (1961, 1975) showed that competitive goals and prizes that establish one group over the other only contribute to create further competition and to set groups apart. I myself as a facilitator provoke that sort of reaction in workgroups by simply saying how well a given group performed a random task – in minutes a conversation about who is right or wrong and who is better or worse breaks out – a beautiful moment to let them know that there was no right or wrong answer.

Leaders and followers can improve their dyadic relationships and decrease competition by stimulating cooperativeness. Easier said than done, right? How can I do that then?

By establishing superordinate goals – objectives that have a common purpose and that clearly indicate that one team’s success is dependent on the other’s success and vice-versa. Another way of breaking out in-group and out-group is to make group members spend time together with each other, either by assigning joint projects during which they will have to work together for long periods of time or by making them simply spend time together in a happy hour – for the latter, just be sure to get to the bar first and to make people from each group sit with members of the other groups.

For anyone who has ever watched “Remember the Titans” (Yakin, 2000), the motion picture – based in a true story – is a classic example of how to fend off preconceptions, biases, and an “us versus them” mentality and replace them with a sense of respect for people who you considered to be out-group members.

The beauty of the LMX theory on leadership is that it reminds us that, at some level – whether you believe in God, the Big Bang Theory, or both, or any other theory or super being – we are all the same; we share the same particles, the same fears, the same anxieties; we share the same needs, of belonging, of physiological needs, of security; we share the same tendency toward biases, prejudices, and predictability.

As leaders and followers, we share the tendency to be humans. As leaders and followers, we share the tendency to go beyond. As leaders and followers, there is one question we need to answer: “can we unite against ourselves for our own higher interest?” (Aldous Huxley as cited in Heroic Imagination Project, n.d).

Footnotes

1 – In his original paper, Maslow called the 3rd level “the love needs”, but later interpretations of his paper made famous the “belonging needs”

2 – An in-group is a social group, which a person psychologically identifies with as being a member whereas an out-group is a social group, which an individual does not identify with (Soriano & Bhatngar, 2013).

References

College of the Redwoods (n.d.). Maslow’s Hierarchy. Retrieved from http://www.redwoods.edu/Departments/Distance/Tutorials/MaslowsHierarchy/maslows_print.html

Gleitman, H., Gross, J. J., & Reisberg, D. (2011). Psychology. New York: W. W. Norton & Co.

Heroic Imagination Project (n.d.). Heroic quotes. Retrieved from http://heroicimagination.org/public-resources/heroic-quotes/

Lunenburg, F. C. (2012). Power and leadership: An influence process. Journal of Management, Business, and Administration, 15(1), 1-9.

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370-396. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0054346

Northouse, P. G. (2013). Leadership: Theory and practice. Thousand Oaks: SAGE

PBS (2009). This Emotional Life. Retrieved from http://www.pbs.org/thisemotionallife/

Princeton University (n.d.). Confirmation bias. Retrieved from https://www.princeton.edu/~achaney/tmve/wiki100k/docs/Confirmation_bias.html

Rosenthal, R., &. Jacobson, L. (1963). Teachers’ expectancies: Determinants of pupils’ IQ gains. Psychological Reports, 19, 115-118.

Sapolsky, R. M. (2004). Why zebras don’t get ulcers: The acclaimed guide to stress, stress-related diseases, and coping – now revised and updated. Henry Holt and Co. Kindle Edition.

Sherif, M. (1961). Intergroup conflict and cooperation: The Robbers Cave experiment. Norman, Okla.

Sherif, M. (1975). On the application of superordinate goals theory. Social Science Quarterly, 56(3), 510. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/1291566742?accountid=13158

Taijfel, H. (1970). Experiments in intergroup discrimination. Scientific American, 223(5), 96-102.

Soriano, D., & Bhatngar, A. (2013). Social psych experiment: In-group vs. out-group [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bewEKRRTWVM

Yakin, B. (Director). (2000). Remember the Titans [Motion picture]. USA: Walt Disney.