By Colette Slagle and Jacqueline Reid-Walsh

As Jacqui and I continue our experimental foray into semi-diplomatic transcription, we have made several small observations along the way, both about the texts themselves, as well as reflections on the transcribing process. One such observation came out of comparing two versions of the Metamorphosis; or, a Transformation of Pictures, with Poetical Explanations for the Amusement of Young Persons, an 1810 version published by Solomon Wiatt, and an 1811 version published by Jonathan Pounder.

We transcribed Jonathan Pounder’s 1811 text at the Bodleian Library in Oxford first, back in May of this year. Earlier this month, Jacqui and I transcribed Solomon Wiatt’s 1810 text at Penn State. We noticed that both texts listed the same publishing address (No. 104, North Second Street, Philadelphia) though the people who published the texts were different. Jacqui speculated what their possible relationship might be.

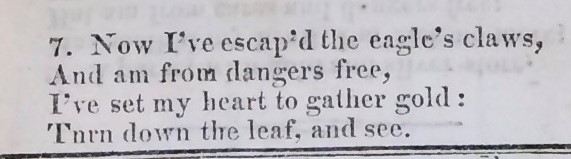

It is useful to give a bit of context about the nature of the texts first. The verses on each flap of the turn-up books are numbered, instructing the reader in which order they are meant to be read. As Jacqui has previously noticed, the first twelve numbered verses are part of the original poem—they clearly correspond with the flaps and the transforming images. The following additional verses were added later, and though the numbers suggest they are a continuation of the original poem, the lines themselves read like an entirely different poem. The flap order also changes with the additional numbered verses—the images seem irrelevant to the meaning of the text after the original twelve verses.

While transcribing Pounder’s 1811 version in England, I ran into a conundrum. In Pounder’s 1811 text there are two 12s listed in his text. One is obviously part of the original poem, while the second is located on the back of the artifact. This second 12 includes 3 stanzas—the longest of any of the numbered verses on the text. At the time, I was not sure where to put this second 12 in my transcript. Did I put it after the first 12? Was it meant to go at the end of the poem instead? I decided to follow the order suggested by the numbers at the time, placing the two 12s next to each other, though it seemed a bit odd. I read the three stanzas as a turning point in the poem, thinking that perhaps it was meant to act as a climactic moment in the text to help shift between the original 12 verses and the additional verses.

After transcribing Wiatt’s earlier 1810 version this month, it became clear that Pounder’s version was more than likely a misprint. Instead of two 12s, the verse on the back of Wiatt’s version was labeled 21, placing these three stanzas at the very end of the poem. Jacqui speculated that the printer likely set the type incorrectly in Pounder’s version—given it needed to be done upside-down and backwards—and simply left the mistake in due to its being an instance of “cheap print.”

Wiatt’s 1810 version with the correct numbering. (Special Collections, Penn State Libraries)

Pounder’s 1811 version with two sets of verses numbered 12. (Bodleian Library, Oxford University Vet. K6 f.92)

Although a simple typographical mistake, it drastically changed the way I transcribed the text—and, perhaps, the way the text was read as well.