By Colette Slagle and Jacqui Reid-Walsh

Because we devoted the last blog to the interconnections between marking samplers and metamorphoric books we decided to examine more closely two handmade metamorphic books made by girls. While our next blog will examine the connections between stitchery literacy and a 19th century artifact made by a American girl Betsy Lewis, in this blog we examine a late 18th century artifact made by Eleanor Schanck and we hypothesize her nationality.

In 1777 Eleanor Schanck created and dated a four-part turn-up book now held at the Cotsen Library at Princeton University. This is one of the few known homemade turn-up books that can be confidently identified as girl-made, as most handmade versions are anonymous, making it difficult to determine their provenance. It is unknown if it was created in England or the United States. In this blog in order to answer this question, we compare Eleanor’s turn-up book to known published British and American editions.

The Cotsen catalog entry describes it as 1 sheet folded into 4 panels with flaps, written and drawn with pen and ink, measuring 27 x 37 cm. When you interact with the object since there are no individual movable flaps, you can only lift the entire top part or the entire lower part. Looking at photos, it is hard to determine whether it had been cut and then later reattached, or if it was always uncut.

The early date of this handmade text raises question about which versions of The Beginning, Progress and End of Man and Metamorphosis could have served as a model for Eleanor. While the 17th century British religious turn-up book was published on occasion throughout the 18th century, the American Metamorphosis is believed to have been first published after 1775 (Hamilton, illustration 26). We therefore compare Eleanor Schanck’s handmade manuscript with the 1650 British 4-part turn-up book printed by Bernard Alsop, the 1654 British 5-part turn-up book printed by his widow, Elizabeth Alsop, and a facsimile of the earliest known American Metamorphosis, printed circa 1775 in Philadelphia (Hamilton 25). Important to note is that the 4-part American Metamorphosis is itself closely based on the 1650 edition, with the exception of one stanza, which we discuss below.

For the most part, Eleanor’s version is similar to the 1650 version, however one substantial difference is the mermaid verse included in each.

The mermaid verse in the 1650 edition is as follows:

“The Mermaids voice is sharp and shril

As womens voices be ;

For if you crosse them in their will,

You anger two or three.”

1650 The Beginning, Progress, and End of Man. Photo courtesy of the British Library.

1650 The Beginning, Progress, and End of Man. Photo courtesy of the British Library.

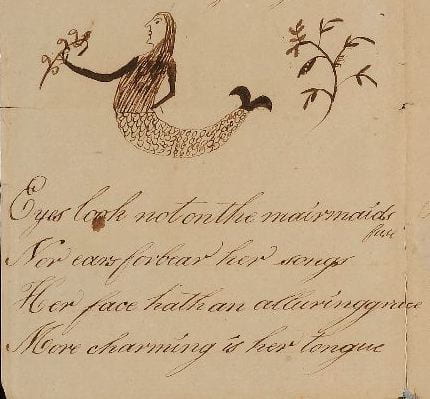

Eleanor’s version is as follows:

“Eyes look not on the mairmaids fase

Nor ears forbear her songs

Her face hath an alluring grace

More charming is her tongue”

1777Adam first comes first upon the stage [manuscript harlequinade]. Photo Courtesy of the Cotsen Library, Princeton University.

1777Adam first comes first upon the stage [manuscript harlequinade]. Photo Courtesy of the Cotsen Library, Princeton University.

Eleanor’s version seems closest to the mermaid verse in the 1654 edition:

“Eys, look not on this Mermaids face,

And Ears, forbear her song :

Her face hath an alluring grace,

More charming is her tongue.”

1654 The Beginning, Progress, and End of Man. Photo courtesy of the Houghton Library, Harvard University.

1654 The Beginning, Progress, and End of Man. Photo courtesy of the Houghton Library, Harvard University.

The mermaid verse in the 1775 American Metamorphosis version is also similar to the 1654 edition:

“Eyes look not on the Mermaid’s Face,

Let Ears forbid her Song ;

Her Features have an alluring Grace

More charming than her Tongue.”

Facsimile of c. 1775 [Metamorphosis] in 1958 Hamilton, Early American Book Illustrators and Wood Engravers, 1670-1870, figure 26.

Facsimile of c. 1775 [Metamorphosis] in 1958 Hamilton, Early American Book Illustrators and Wood Engravers, 1670-1870, figure 26.

While the mermaid verses are quite similar in both the 1654 edition and the 1775 American Metamorphosis, Eleanor’s is most similar to the earlier British edition. For example, she uses “forbear” rather than “forbid” in the second line, “face hath” rather than “features have” in the third line, and “More charming is her tongue,” rather than “More charming than her tongue.” For these reasons, we speculate that Eleanor was working from the British editions, not the American.

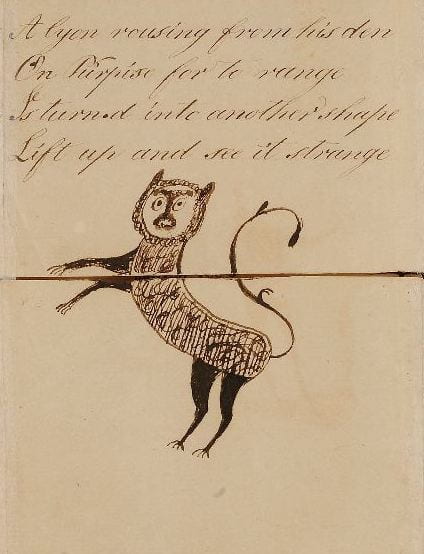

Another significant difference we noticed between Eleanor’s handmade text and the 1650 British edition was the spelling of the word “lyon.” The only known printed versions of the text that also uses this spelling is a 1688/9 version owned by Anthony Wood and published by Dunster, held at the Bodleian Library, an undated 17th century version, held at Penn State, and an undated British edition, owned by a private collector. Based on this circumstantial evidence, we think Eleanor was likely British.

Facsimile of 16XX The Beginning, Progress, and End of Man. Photo Courtesy of Penn State Special Collections.

Facsimile of 16XX The Beginning, Progress, and End of Man. Photo Courtesy of Penn State Special Collections.

1777Adam first comes first upon the stage [manuscript harlequinade]. Photo Courtesy of the Cotsen Library, Princeton University.

1777Adam first comes first upon the stage [manuscript harlequinade]. Photo Courtesy of the Cotsen Library, Princeton University.

*For a discussion of Eleanor Schanck’s artistic style, please see 2017 Reid-Walsh, Interactive Books pg. 218-219.