Jacqui Reid-Walsh

On February 11, 2022, I had a dynamic practice printing session with Bill Minter, Senior Book Conservator, at the Conservation Center of the Penn State University Libraries. We worked with images of a couple of blocks that I commissioned several years ago based on the Bodleian copy of the Beginning, Progress and End of Man.

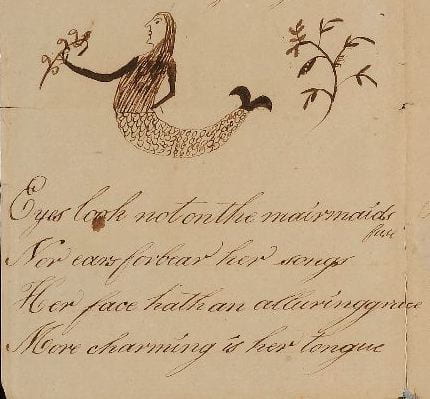

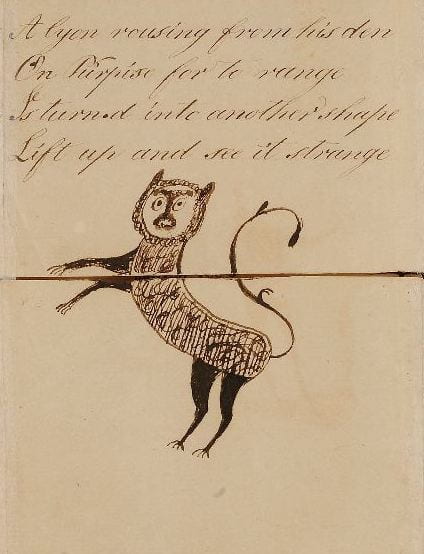

Bill first worked with the splendid lion block, quickly achieving a clear image of the lion (figure 1). Then we played with making impressions of the Eve/mermaid. Interestingly, looking at the Eve die block, it seems to have little definition in the top half of the figure – her face seems to have no etched lines and so looks indistinct (figure 2).

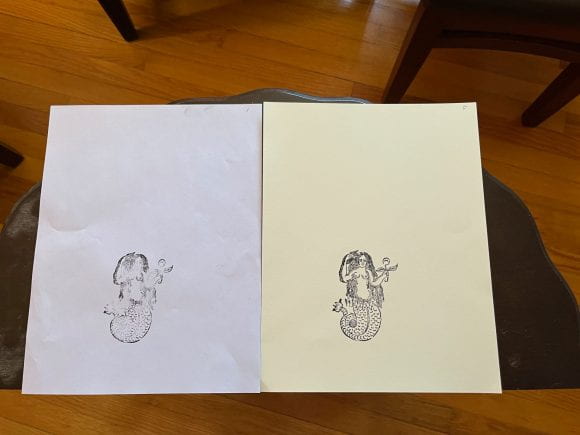

Bill printed several impressions and experimented with adjusting the amount of ink and different kinds of pressure. There were small changes in the image, but there seemed to be a problem with the die because some low areas were not printing. This was corrected by adding a simple piece of tape to raise the paper on the tympan – printers call this “makeready.” This revealed fine details on the die that were previously not visible. He also experimented with using different types of paper: regular paper, Japanese paper, and then “Stonehenge” paper made by the Rising Paper Co. which is 100% cotton and used for printmaking. The final version splendidly shows the fine details (figures 3a, 3b)! After all of the use, though, Eve fell off the wooden block! Bill corrected some of the trouble by re-attaching the die with a solid layer of the double-sided tape and put her back together again (figure 4).

One photo shows me pulling the handle of the Washington Press, an elegant machine (figure 5). Bill used the tympan and frisket. When I asked about the history of the press, he said it was built in 1839 just before the manufacturer (R. Hoe & Company) started to use their name across the front in about 1841-42.

The aim of this exercise was to see if we could do a project based on photographing the entire Beginning, Progress and the End of Man we have at Penn State. To my knowledge this is one of three versions housed in American academic libraries (the other two being Harvard and Princeton) and notably they are free-standing and therefore manipulatable objects. The one I worked with in England at the Bodleian Library is glued to the gutter of a large volume owned by the 17th-century collector Anthony Wood. My dream is to have the entire object photographed and blocks made of the entire set of images in the 5 panels.

Printing the entire turn-up book on rag paper on a hand press we could reconstruct how the images were printed and so understand the clarity and dynamism of the images. Significantly, using rag paper would demonstrate how the material of the turn-up enables the interactive design to be engaged with fully. In this way, we can gain insights in the how the 17th and 18th century interactors engaged with the turn-up book making, unmaking, and remaking the transformations. Perhaps this ease of manipulation was one reason why it was popular for hundreds of years on both sides of the Atlantic.