Continuing with the theme of vector-borne diseases from my previous post, today we’ll be covering Lyme Disease.

The name is ubiquitous throughout Pennsylvania and much of the Northeast. This is unsurprising, considering the incidence of the disease has almost doubled since 1991. Spread to humans via the bite of an infected black-legged tick (also known as the deer tick), the illness is caused by the bacteria Borrelia burgdorferi.

There is substantial history behind the names of both the disease and the bacterial cause. “Lyme” comes from the town where it was first identified in the 1970s (Lyme, Connecticut). At the time, children and adults alike in the area suffered from similar symptomatology with little understanding of what was going on. It wasn’t until 1981 that a researcher, Willy Burgdorfer (hence “burgdorferi“), found the causative bacterium.

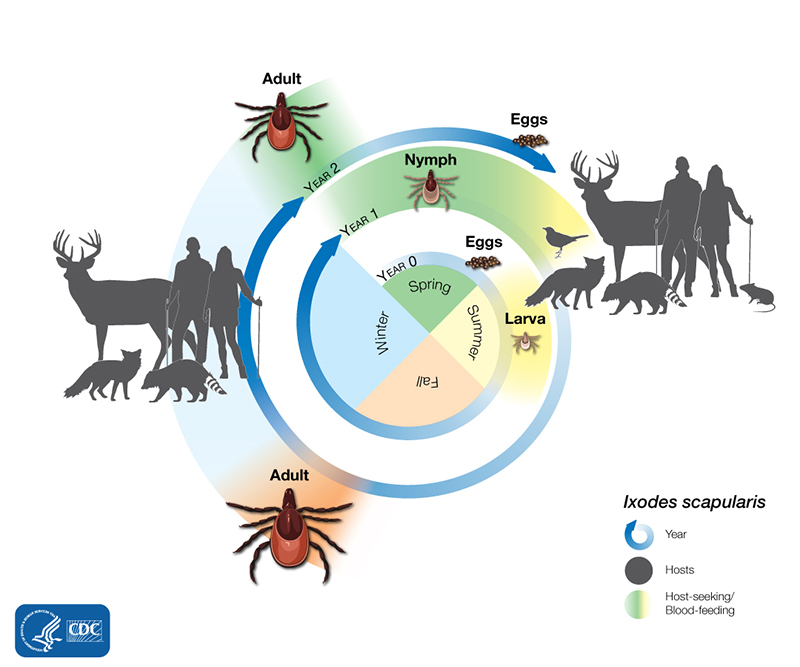

Typically, ticks acquire the bacteria by first biting another infected animal. This is largely related to the life cycle of the tick, which requires it to have blood meals during each of its stages of development. Generally, they need a different host for each meal; this host-hopping results in the propagation of bacteria. In spite of the tick’s name, deer actually are dead-end hosts for Lyme disease. They can’t get infected with Lyme, nor can they spread it to ticks.

Once they’ve found a human host, the ticks feed off of them for around 36-48 hours. Depending on where they’re located on the body, they can complete their meal entirely unnoticed. Not only is this due to their small size, but also because their saliva can anesthetize the area around their bite, leaving their host unaware of them. This makes it especially important to check yourself for ticks, especially after going in a high risk area (such as in the woods or in areas with tall grass).

Inside the body, the bacteria often leads to fairly universal symptoms, such as fever and headache. However, one of the more notable results is the characteristic erythema migrans rash, which often presents itself as a bullseye and can help with Lyme disease diagnosis. While these initial effects are fairly mellow, the disease can eventually lead to much more serious complications, such as joint or heart problems and nervous system symptoms.

This makes it important to get treatment early. Typically, a treatment regimen includes antibiotics such as doxycycline; if detected early enough, this is sufficient to prevent late Lyme disease. Serious cases may require longer courses of antibiotics. Some also experience Post-Treatment Lyme Disease Syndrome, in which pain and fatigue continues well after they should be cleared of the bacteria. The exact cause is unknown, though some theories include it being an autoimmune response, a continued infection that is hard to detect, or a different illness altogether.

Overall, Lyme disease isn’t very pleasant. So what can you do to avoid getting it? For one, stick to the trails when you’re out hiking. You can also gear your clothing choices toward protection: for instance, it’s recommended that you wear long pants and sleeves while hiking and opt for light-colored fabrics that make any ticks climbing on them more visible. Insect repellant, such as DEET, is also recommended (even though ticks aren’t technically insects). Also, as mentioned prior, be sure to check yourself for ticks after spending time outdoors, and remove any attached ticks as soon as possible. Taking these types of precautions will minimize your risk of getting Lyme disease (along with any other nasty tick-borne illnesses).

With that in mind: wash your hands, wear a mask, and be careful on your next hike!

.

References

“History of Lyme Disease.” Bay Area Lyme Foundation, www.bayarealyme.org/about-lyme/history-lyme-disease/. Accessed 24 Jan. 2022.

“Lyme Disease.” American Lyme Disease Foundation, www.aldf.com/. Accessed 24 Jan. 2022.

“Lyme Disease.” The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 19 Jan. 2022, www.cdc.gov/lyme/index.html. Accessed 24 Jan. 2022.

“Lyme Disease.” Pennsylvania Department of Health, Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, www.health.pa.gov/topics/disease/Vectorborne%20Diseases/Pages/Lyme.aspx. Accessed 24 Jan. 2022.

“Prevent Lyme Disease.” Connecticut State Department of Public Health, State of Connecticut, portal.ct.gov/DPH/Epidemiology-and-Emerging-Infections/Prevent-Lyme-Disease. Accessed 24 Jan. 2022.

This was a very informative read! I hear about these ticks a lot, especially during the summer. I don’t think I’ve gotten a tick bite before (I’m not a super outdoorsy person so that may explain it), but I have found multiple on. my dog, but at a super late stage when they are big and hard to detach from the skin. It’s very shocking to find them! I will definitely be careful this summer and take precautions to avoid Lyme disease.

This blog made me feel so uneasy ever going into the woods again. I used to run cross country, and after we would run trails in the woods we would always jokingly, but somewhat seriously do a tick check. Now, I will be taking tick check seriously. I was slightly uneasy in the beginning, but when I read that their saliva can anesthetize the area, that genuinely turned my stomach. It also disturbed me that they can stay on your body for 36-48 hours. My cousin went hunting when he was younger and got severe Lyme disease because he did not know that the rings are a sign of it. He was on intense antibiotics for a while. While this makes me uneasy, it is fascinating how nature works and other forms of self-defense. Well done, this was intriguing!

Hi Jasmine! I have always thought that animal-borne pathogens are some of the most interesting types of pathogen! Honestly, I think that Lyme’s disease was one of the first diseases that I have ever heard of, and when I was younger, I was strict and paranoid with myself after playing outside out of the fear of having possibly “contracted” a tick. I probably still am. This was an informative post indeed, as always. Also, great use of graphics to help convey understanding of more important/detailed information (and good advice at the end too). Speaking of insect-bacterial relationships, if you’re interested in something that’s not a pathogen, I suggest checking out Wolbachia – one of the coolest species. Anyways, looking forward to the next blog post!