Welcome to my final Civic Issue post about global gender inequities in education. As a recap, let’s discuss what the first two posts were about: post one talked about what the issue is, where it exists, and what has already been done in terms of intervention to solve it. Post two went more in-depth as to the ethics of intervening and possible courses of action should intervention occur. Today, for post three, I would like to discuss two things: whose responsibility it is to intervene and why global crises are difficult to address.

Whose responsibility is it?

On whose shoulders does the responsibility lie to solve this issue? Let’s break it down by the scales we could attack this issue from.

International

Organizations like the United Nations and treaties like the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) are specifically designed to solve international problems — usually in a humanitarian-centered way. These organizations provide one, large system for addressing these issues because the problems spread across multiple, smaller systems (countries, states, etc.) Since gender inequities in education exist across the board, it could be argued that these organizations have a responsibility to intervene on a large scale.

National

It could also be argued that the responsibility to solve this issue lies on the governments of the countries where it exists. After all, many educational systems differ from nation to nation, so maybe it would be best for each country to individually assess and work to solve their inequities. Keep in mind, however, that if the issue of women and girls not having access to education was a problem created under the same system that is still in place, it’s likely the actions of the nation would be ineffective.

Local

People often say “it takes a village,” and they might be right when it comes to things like this. From teachers to parents to school administrators, there are multiple things that can affect whether or not girls have equal access to a proper education. A blog post from Global Partnership sums it up well, saying:

“Schools are responsible for ensuring safe and inclusive learning environments, free from school-related gender-based violence and unfair student treatment… Teachers are responsible for inclusive instructional practices and fair disciplinary approaches as well as for promoting active discussions on gender issues… Parents are responsible for ensuring their children have equal opportunity to attend school, and for providing equal support and encouragement regardless of their child’s gender… All of us, as community members or professionals, are responsible for monitoring governments, schools and teachers, to challenge stereotypes and ensure discrimination is not tolerated.”

Additionally, depending on the government format in a given area, the local government might have control over curriculum choices and other school-wide programs that affect this issue, and therefore have responsibility.

Why are global issues so hard to solve?

The best solution to combat gender inequities in education is probably formed from a combination of different kinds of intervention from all of the jurisdictions listed above. Like most global issues, a combined approach is necessary because of how globalized our world is and how intersectional issues are. First, globalization has made us unbelievably interconnected and because of that, what we do inevitably affects ourselves, our neighbors, and the entire world. Addressing an issue, especially an intersectional and international one, becomes so much more complicated because of all the stakeholders that are invested because of how globalized our world is. For example, if a country decides to build more schools to solve the gender inequity in education, they have to consider not only the students, teachers, and administrators, but also how it will affect the job market, the land, foreign affairs, the economy, other citizens, and the list goes on. Looking at the whole picture, however, is a key part of actually solving local, national, and global problems. If we don’t solve a problem for everyone, then we’re not really solving the problem at all; we’re just displacing it. Take the emergence of birth control, a movement largely impacted by Margaret Sanger. Sanger was an advocate for providing birth control to women, as well as information on sex, pregnancy, and contraception. Sanger accomplished much of her mission, and changed the landscape of women’s reproductive rights. However, much of what she did was only accomplished because she was fighting for birth control on the grounds of eugenics. Sanger advocated for birth control not to increase a woman’s bodily autonomy, but to prevent “lesser” parts of the population from reproducing (especially those who have a disability, are people of color, or are poor). Some historians believe this was strategic because Sanger got lots of “wins” for reproductive rights — but she did it at the expense of others, and it’s led to problems in healthcare today. Many horrific, eugenic-based practices still exist — and still more greatly affect the poorer, disabled, and marginalized populations around the world. Without considering all stakeholders, groups are inevitably left with the displaced issue. Of course, keep in mind that satisfying all stakeholders of a complicated, intersectional problem is easier said than done… probably impossible to some.

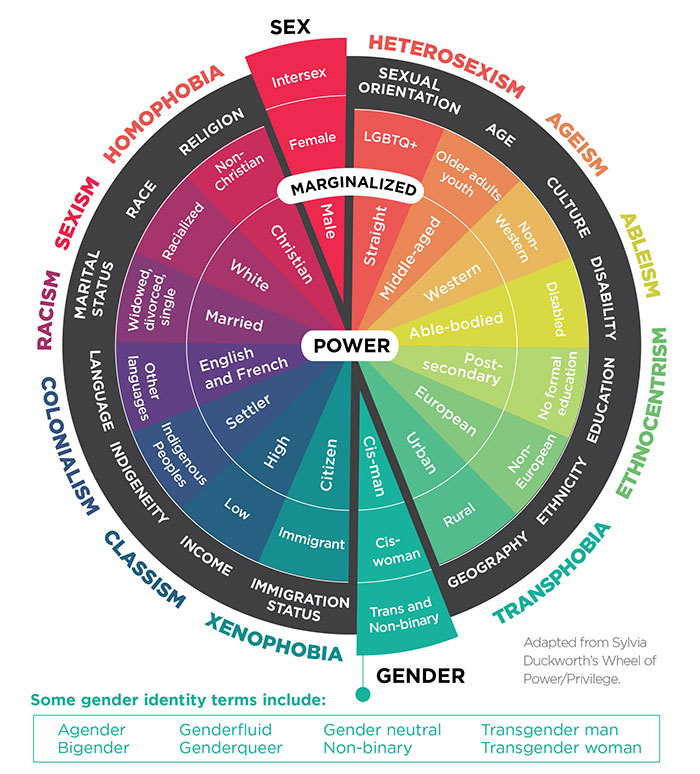

Secondly, the intertwined nature of issues causes major complications in solving a global crisis. Quality of life is no longer affected by a single thing like your income, your family, or your gender. Issues are so much more intersectional these days, meaning multiple aspects of your life are affecting multiple issues in your life and the world — all at once. For educational gender inequalities, somebody’s gender, race, religion, socioeconomic status, immigration status, language, family, access to transportation, ability to afford textbooks, disabilities, age, marital status, sexual orientation, sex, and political affiliation — to name a few — could all affect whether or not they can attend school and what kind of education they will get there. A graph below from “Meet the Methods Series: Quantitative intersectional study design and primary data collection” shows a version of Sylvia Duckworth’s Wheel of Power/Privilege which helps to break down intersectional power structures:

Where do we go from here?

Considering the kinds of difficulties in solving a global issue like gender-based educational inequities, I want to ask you the three overarching questions that have been driving this entire civic issue:

Does someone/something need to intervene to address this issue?

Who/what should intervene?

How? What courses of action should they take to help lessen the problem?

These are the three key questions I see as essential to creating a better educational environment for women and girls everywhere. I know we are college students and not policy experts, and probably not at a point in our lives where we can easily solve widespread global issues that harm people in real time. But I think it’s worth a shot to start thinking. We are the future. Why not have as many brains thinking about a solution as possible? Together, we can and we will ensure every woman and girl — no matter who they are or where they come from — can get a quality education, just like anyone else.

Sources:

https://www.globalpartnership.org/blog/who-responsible-ensuring-gender-equality-education

https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/52352.html

Thank you so much for following along the journey of my civic issue blog. I know it's required lol, but I hope you enjoyed! P.S. I wrote this last night. I worked on it for about an hour at like 10pm. I was writing in this post on sites.psu.edu and I was at 970 words. I hit "save draft" and it took me to a page that said "Something went wrong". All my work disappeared. I consulted my IT stepdad. It was all gone. All my beautiful work. So the moral of the story is... do you remember my blog's name? Yeah, God was not there.

Martina Bouder

March 17, 2022 — 3:13 pm

I love how you break down each level at which action needs to happen on this issue, but also that you addressed what makes it so difficult to tackle a global problem such as this. I found it super insightful that you mentioned Margaret Sanger and the progress she made on reproductive rights while also being based in eugenics and racism – something that it seems most reproductive rights groups have roots in. It certainly is important to recognize that history and move forward in a way that is not rooted in such ideologies, and I think that what you propose is the way to do that. While we may just be college students, education on issues like this are how we make change in the future.

Brennan Eggleston

March 17, 2022 — 3:24 pm

I have really been a fan of this blog this semester because of both your knowledge and passion for this issue. To answer some of your final questions from the end of this post, I think that a “privileged actor” (a country with plentiful resources, both human and financial), whether it be the united states or another developed nation, should in fact intervene on behalf of education for women because there is no reason that women across the world should not have access to education. As far as courses of action, I am no expert, but simply establishing schools and staffing them as well would go a long way. Great work on this blog post!

Justin Yutesler

March 17, 2022 — 3:25 pm

I really appreciate the format of these blogs and how organized you keep them. The headers flow really well and help make your argument a lot more digestible, which is especially important for such a complicated issue.

Also, props for rewriting the entire thing after having already finished it once- I’m always paranoid the same thing will happen to me lol.

Andres Aguirre Torres

March 17, 2022 — 10:19 pm

First, I have to say that your blogs were very well structured and written. Second, you did a great job re-writing everything, which significantly improved your blog. Lastly, I would say it is hard to solve this. For example, in countries with less democracy, it might be difficult because usually the public school system is corrupted, and if an outside organization intervenes it would only be a temporary solution, but in the end, it would be the same. But, it is possible that if a developed country intervenes, it could make a change.

Sophia Griffin

March 20, 2022 — 7:51 pm

Major props to you for rewriting your entire blog and still making it such high quality. I’ve been there and the frustration is indescribable and sometimes enough to make me reconsider channeling a ton of effort into a second version. Considering your content, I think you manage to tackle the most significant struggle which is that in world we live in today there is often no clear demarcation of where responsibility falls or what that responsibility looks like. For me, the best first step I think the whole world needs to take is acknowledging how deeply rooted these problems are and reframing our perspectives to understand our individual roles within a larger context.