A, B, C, D and F. What do they all have in common? Of course, they are all part of the alphabet, but they also make up the letter grading system in schools and universities across the country.

Grading scales’ history goes back to as early as the 1600s, however it wasn’t until 1897 that Mount Holyoke College became the first to use letters tied to a numerical/percentage scale. Later, K-12 schools also began to implement letter grades; due to mandatory attendance laws and a subsequent increase in enrollment, a detailed descriptive report for each student was losing popularity to a much more time-efficient letter notation. And with the desire for standardization of grades across the country, grading scales have been embraced by the US for decades.

Now, the longtime tradition has been facing controversy regarding how effective the letters are in showing the correlation between success and learning. So, do we need letter grades?

There’s a reason letter grades have been around for so long. The most obvious reason is that they are universal, making the meaning behind them easily understood no matter the circumstances or geographic location. Virtually every parent, teacher or child knows the difference between an “A” and “F” simply by glancing at the letter. Even with minor changes, letter grades can allow students to seamlessly track their academic progress even if the location of learning changes. The simplicity of the scale as opposed to its historic descriptive counterpart provides many benefits to educators as well; teachers can easily compare how a student is doing in comparison to their classmates and provide extra help as needed just by looking at a letter.

But, others believe that it is time for a change. Opponents argue that the simplicity of the letters can also be a drawback as they are extremely subjective. In other words, the actual grading is not standardized. Although this may not be true for subjects like math and science where answers are either right or wrong, subjects like English are more interpretive and the grade received is based on how the teacher feels about the answer. Consequently, one teacher may grade an essay a B while another teacher may give it a C. In the end, the letter grade does little to inform the student on how well they did actually writing the paper.

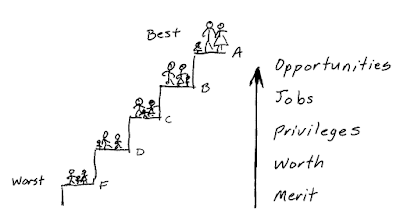

This also has negative effects as many students and parents base intelligence on the grades received.

With high stakes of GPA, college acceptances and job offers, many students value getting the A rather than actually learning with current grading systems. As such, many instructors are looking to transition their grading to be based more on student effort on the assignment or giving narrative feedback in order to motivate students to grow academically. It’s too soon to tell, but these new ideas could usher in a new future of grading.