Hello! Last week, I briefly remarked how music is not entirely defined by a popularity contest, and how I felt that the best music “transcends the playlist,” going beyond the background white noise in your car or at a party. I was careful in wording that statement, as it would be shortsighted to imply a song’s popularity is not at all indicative of its quality. Moreover, the success of an artist (and in turn their songs) in the music industry is traditionally dictated by their works’ exposure, whether it be through sellouts of records in the 60’s or mass streamings in the 2010’s. Billboard, an advertising journal turned music publication, has been ranking songs by the aforementioned measures in the U.S. for decades now with their historically versatile charting system. These various charts – the most popular being the “Hot 100” – have become industry standards, defined by genre, quantity (i.e. top 100 or 200), and even country. The charts themselves came relatively later on in the life of Billboard itself, however, and it is the story of the two that I will be diving into this week!

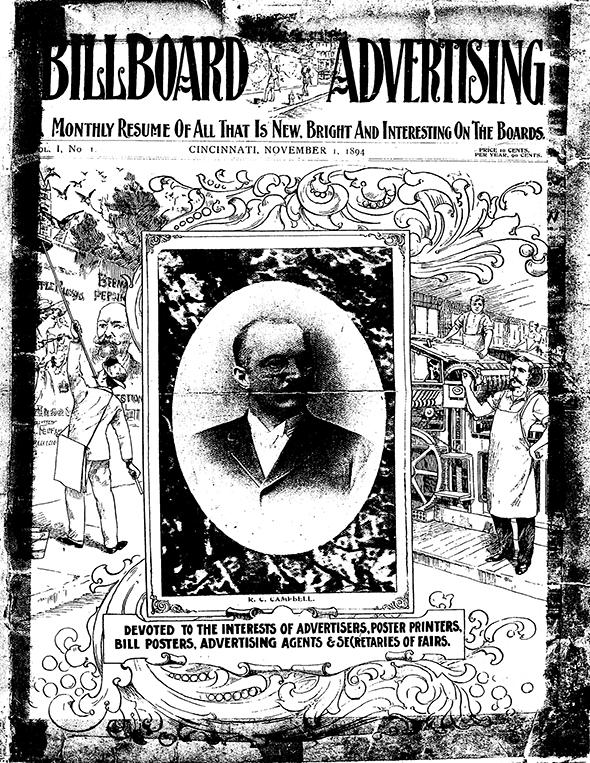

Billboard began as Billboard Advertising with no intention of revolving around the music industry. The startup was launched in fall of 1894 by partners William H. Donaldson and James H. Hennegan as a journal-esque publication for billposting businesses. The first issue circulated November 1st, 1894, covering eight pages with a cover price of 10 cents and a yearly subscription of 90 cents. It’s cover page stated that the new publication was “devoted to the interests of advertisers, poster printers, bill posters, advertising agents and secretaries of fairs,” though such intentions would change in a few short years.

The publication initially took on discussions of the “science of advertising,” with headlining columns “Bill Room Gossip” and “The Indefatigable And Tireless Industry Of The Bill Poster” suggesting a seemingly predictable future direction for the organization’s content. However, in June of 1896, Billboard Advertising set forth the first of several major shifts in its lifetime, with the first being towards the entertainment industry with the introduction of a “Fair Department.” The Fair Department covered billboard-advertised carnivals and fairs, while the parent magazine featured ads throughout the pages for attractions similar in nature. By February of 1897, the first metamorphosis had come to fruition, as the publication’s handle was shortened to The Billboard (remaining so until 1961) and its pages were now crammed with countless listings of fairs, carnivals, and other related advertisements. New columns such as “Stage Gossips” arose at the time, dedicated to coverage of the then-budding entertainment industry.

November 1st, 1894. Billboard is soon to be 125 years old!

As time pressed on, The Billboard continued with its newfound focus, working in additions of new columns dedicated to followings of veteran performer’s activities. The Billboard also created the “Letter Box”, which essentially acted as a traveling performer’s mail forwarding service. Specifically, the Letter Box provided a column of names of performers whose mail was gathered at the Billboard offices (i.e. fan mail). Difficulties due to technological constraint made for a daunting task, though the “Letter Box” column successfully created a sense of connection that quite literally made The Billboard the “hub of the entertainment community.”

Yet another small-scale though notable shift in The Billboard’s agenda occurred in the early 1900’s with the first mentionings of musicians appearing in 1904 issues. In September of 1905, the first column solely dedicated to music was published, and song promoters dubbed “song pluggers” were featured in newer issues. In 1940, the publication historically introduced its first weekly tallies of songs ranked by sales, with the first “No.1 hit” being “I’ll Never Smile Again” by the Tommy Dorsey Orchestra, with lead vocals by Frank Sinatra. 15 years later, the “Top 100” charts were compiled in 1955, though the eye-catching “Hot 100” debuted in 1958. From their debut onward, the Hot 100 and sister charts themselves evolved almost separately from the magazine, with Billboard contributors adapting their calculations to various technological changes changing music consumption (i.e. 45 RPM singles in 1949, CD’s, digital downloads, and 2012’s streaming).

The forerunner of Billboard’s charts. The regionalization of “popularity” is rather disregarded in Billboard’s later charts

A snapshot of the kind of content The Billboard was featuring. Talks of such technology in a mainstream newspaper are largely unheard of, and would only find a modern day equivalency in an online forum.

In 1961, the publication went through a yet another transition, becoming Billboard Music Week (with its final renaming to just Billboard occurring two years later) and abandoning the coverage of general show business and tightening the scope on music. During the early stages of the revamp, the magazine was a weekly business journal for the professional musician (notably featuring discussions of up and coming technologies), though would evolve into a music editorial for the avid listener over the next few decades. 2005 saw the final major transition in a history of constant reshaping, with a total redesign and a slightly broadened scope to encompass all forms of digital/mobile entertainment. The charts, practically separate from the magazine, continued not only their technological evolution to their current online format, but their growth in prominence in music industry. The chart’s incredibly simplistic nature in discerning leading tracks begot quick attention from and considerable influence over the public. This not only lent credence to its quickly established name, but to its continued usage as the industry’s hit scale.

The iconic logo of the Billboard’s “Hot 100” Charts.

A 2005 issue following the the May 2005 restructure. The mentioning of a then new Xbox 360 showcase the new policies of broadened horizons implemented by newer leadership.

Despite residing largely online, Billboard continues to offer print magazines that have only become increasingly aesthetic in recent years.

To this day, it remains undeniable how integral the Billboard Charts have become in the music industry. However, their validity in recent years has come under fire, particularly due to the advent of streaming and its subsequent reminder of how incredibly complex music consumption has become. Various music critics and journalists have questioned in recent years how comparable Billboard achievements are across generations, raising awareness to the reality of Billboard’s arguably disconcerting track record as a measure of hits. Author Steve Knopper (“Appetite for Self-Destruction: The Spectacular Crash of the Record Industry in the Digital Age”) remarked for The Washington Post that comparing the success of Kanye West or Drake by today’s Billboard’s charting standards to the likes of Michael Jackson in the 80s or The Beatles in the 60s is “like apples and oranges” due to “a completely different type of success and consumption.” Cultural critic Chuck Klosterman furthered Knopper’s argument, questioning alongside author Donald S. Passman (“All You Need to Know About the Music Business”) whether the charts are even all that relevant anymore beyond satisfying minds curious about which track sits at No.1. Donald Passman himself noted how pre-digital age charts were actually based specifically on record shipments to stores, and thus record companies would unethically send copious amounts of records to stores in attempts to boost chart positions. Klosterman also argues that charts are poor indicators of a song’s actual cultural impact, comparing how although Prince had five No.1 hits, an incredibly (if not equally) influential Led Zeppelin never had one, making for an unresolved conundrum of Billboard’s Chart integrity as a whole.

Silvio Pietroluongo, the VP of charts and data development, believes that Billboard has been “fairly nimble on downloading and even more so on streaming to make sure we’re reflecting where the music consumer is going.” Back in 2013, he was also on record for saying that “the Hot 100 is, by leaps and bounds, our most-trafficked chart … It’s still the most-quoted chart among media, labels, and PR companies when there is a success story to publicize.” I find it difficult to contest the notion that the Hot 100’s clout remains pervasive, though how “nimble” they have been with keeping up with technological change is questionable given growing ease of piracy. Regardless, there are plenty of arguments for and against the Billboard charts, though one thing is certain – when pop-culture looks to who is succeeding and who is not, the likes of the “Hot 100” help guide the way, for better or for worse.

*Note: The topic of the “Hot 100” and fellow chart’s validity is incredibly complex and leaves room constant back and forth. For example, as a counter to the Prince/Led Zeppelin example, Led Zeppelin never really released any singles of their most popular songs during their heyday or played into the strategy necessary to chart high (sounds awfully familiar). Because of this, it should really come as no surprise that Led Zeppelin never had a No.1. Arguments like these can drag on, though to do this topic justice within the context of a single blog post, dilution was necessary to avoid long-winded, inevitably off-topic discourse.

Wow! I had no idea that Billboard had such a rich history. I love that you included the pictures of old Billboard advertisements. It is very interesting how it has transformed over the years and how it has adapted into what we know as the Hot 100. Thanks for sharing!