Are you a seeker of spice? Does the idea of “burning” your tongue with the hottest pepper in the world appeal to you? According to Guinness World Records, the current hottest pepper in called the Carolina Reaper, which clocks in at 2.2 million Scoville Heat Units.

So, first things first…does eating a pepper actually burn your tongue?

The answer is no, well at least not in the same way as hot chocolate does.

When you burn your tongue by drinking a hot substance like coffee, physical damages is being done to the taste cells in the mouth. They can get scarred or burned quite easily, and you may have noticed you have trouble tasting and that your tongue/other part of the mouth feels rough within the burned area.

However, peppers have a different operational system for getting you to “feel” the heat.

Capsaicin (full scientific name: 8-methyl-N-vanillyl-trans-6-nonenamide), the molecule that is concentrated within the placental tissue of pepper (NOT the seeds, tell your friends that new fact of the day), is source of a chili pepper’s heat.

What happened when you eat items containing chili pepper?

The capsaicin molecules activate the TRPV1 receptor in a chemical fashion, which signals an influx of Na+ and Ca 2+ ions into the cell. Coincidently, this receptor is also the same one that is triggered by intense heat or a physical abrasion. So, even though one feels the sensation of burning after eating a pepper, that’s all it is – a sensation. There’s no physical burning of tongue when eating a pepper (unless you heat that pepper in a microwave and put it immediately on your tongue of course).

The mechanism behind this “burning” sensation of capsaicin is studied through chemesthesis – the chemical mechanisms by which we feel burning, cooling, and even the bubbly feeling of carbonation of foods. These sorts of sensations are classified differently because they go through different nerves, specifically the trigeminal nerve. What also makes these sensations different from your basic tastes is the way we can become desensitized to them.

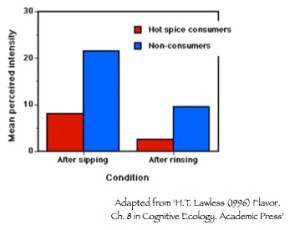

First look at the following chart, which shows you not only how powerful of an irritant capsaicin is, but also how long that feeling of irritation persists.

One of the most common things studied with capsaicin is desensitization. Desensitization is the process by which you would rate something less intensely because of previous exposure to it. Experiments have showed that participants tasting a variety of capsaicin-infused samples show acute desensitization, with intervals between sample of 2.5-5 minutes and chronic desensitization, where they rate the intensity of the same sample over the course of days, with each subsequent day the intensity rating is, on average, less than before.

What’s also cool is that the intensity of the sensation is different based on exposure. Many studies have been done comparing the intensity ratings of capsaicin-fused samples from people who are frequent spicy food eater vs. people who rarely consume spicy foods.

Yes, there is more to the Food Science Building than just the Creamery on the first floor. The second floor contains a variety of booths and other testing rooms where all kinds of food products and solutions are being tested. Companies and grad students alike test out their products to *paid* participants. I’ve worked in the sensory lab for about a year now, and in my time we’ve tested everything from ice cream to perogies to wine. We’re alway looking for new participants, so if you’re interested in being paid to try food, send an e-mail over to Jennifer Meengs, the coordinator of the Sensory Center, at jas138@psu.edu.

A cool experiment being conducted in the sensory food science lab here at Penn State involves the use of a capsaicin mouthwash given to non-spicy food eaters (using an intensity-matched bitter tasting mouthwash as the control). At the start of the experiment, they rate a whole bunch of different sample including sweet, salt, bitter, and yes, some that have capsaicin it them. After rinsing with the mouthwash twice every day they’ve come back to lab and again rated the same samples based on their intensity. The goal was to see the capsaicin-mouthwash participants rate samples of all the tastes, not just those with capsaicin, less intensely. The work so far is going well, and the lead researcher hopes that this work will be used to help patients with burning mouth syndrome become less sensitized.

Burning mouth syndrome is especially difficult to diagnose because the causes are most unknown. There are several “types” of burning mouth syndrome indented, with the first type having no known cause. Type II is often associated with anxiety, and Type III may be contributed by some allergies.