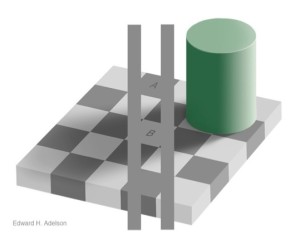

We’ve seen a great deal of examples of illusions in Dr. Wyble’s lectures. The overwhelming majority of these were visual, like this beauty right here.

Knowing that items under a shadow appear darker, our brain compensates by making B appear lighter despite the fact that our eyes can perceive both squares as the same shade.

“Illusions” of context and framing effects plague the sensory world, so let’s explore a few instances of how context can affect sensory results.

Probably one of the best examples of this comes the following study description. In the study participants are given two sets of samples that are solutions of sodium chloride and water. One set, unknowingly to the participants deemed the “low” set, contains three samples at 12%, 18%, and 25% sodium. The “high” set contained three samples at 25%, 35%, and 50% sodium. After each sample they had to rate the taste on 1 to 7 Just About Right scale, with 1 meaning “very much not salty enough,” 4 meaning “Just about right,” and 7 meaning “very much too salty.”

Since the 25% solution was in both the high and low sets, you would think that participants would rate them both as the same intensity, right?

Wrong!

Turns out it is really dependent on the context of which the sample is presented in. It can make more sense when you look at the graph below.

After tasting the 12% and 18% solutions, you can see how a person, after tasting the 25% sample, could rate that one towards a “too salty” rating. On the other hand, if the person happened to taste the 50% and the 35% samples before tasting the 25%, then the 25% sample would seem much less intense.

I helped run a similar lab with students taking the sensory class (FDSC 404) with sucrose/water solutions to help them see how context can really shape the ratings of samples.

Expectations also a play a huge role in perception. My boss last summer liked to use an example called “The Best Italian Restaurant in the World”. She would set up the scenario of you walking into this restaurant: the whole place smelled like Italian seasoning, there were red and white checkered table cloths, soft music played in the background. You sat down and then the waiter brought you your food: a roll of sushi. It wouldn’t matter if that sushi was some of the best sushi you ever had, the fact that you were expecting to be served delicious Italian food is going to impact how you perceive the sushi.

Timing is also another type of context effect. For example, let’s say creamery conducts an ice cream test to gather information about liking. However, they would get different results, on the same exact samples of ice cream, by simply changing the month the test was presented. Think about it….which would feel like a better time to enjoy some ice cream, January or July?

These effects can on some extent be compared to the confirmation bias examples we learned in class. All kinds of context effects can be out there. Sensory researchers know that they exist, so they must tread through experiment design carefully.

Concepts like the “halo effect,” which you may have learned about in an earlier psychology course, also exist in sensory. The halo effect describes the concept of how one positive attribute of a product can influence other, unrelated attributes of the same product is a positive direction. For example, thinking an attractive person must also be nice, good at sports, etc.

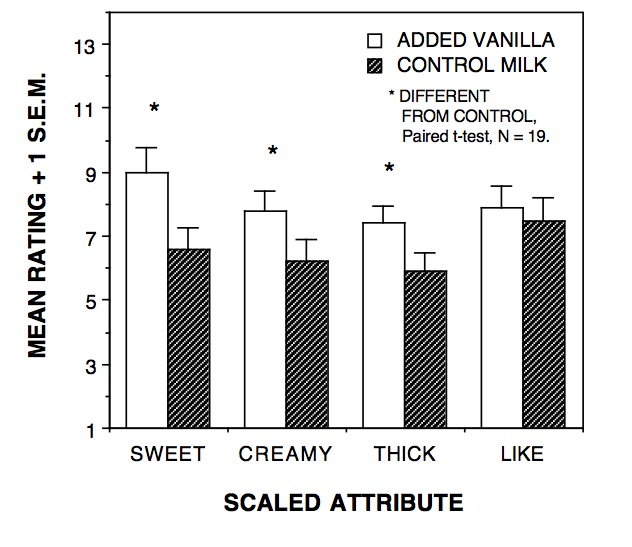

In this study, a couple drops of vanilla extract were added to samples of low-fat milk. Looking at the graph below, it would make sense that the perceived sweetness of the milk increased. However, the participants also rated the milk with the added vanilla as more creamy and thick, attributes that the added vanilla would not naturally affect whatsoever.

As fun as exploring the extent these context effects can be, knowledge about them is valuable for companies and researchers who are trying to achieve accurate and unbiased results.

One group that is good at avoiding context biases are groups that are used for Quantitative Descriptive Analysis. I remember at Smucker’s serving a lot of these types of panels. QDA is conducted by a panel that is trained using very specific food items. They go through hours of these trainings, basically learning how to rate certain items on the same scale. The cool thing about QDA is that because the group is so well attuned to each other while training, they work almost like a machine. For example, after being led through many sessions on chocolate frosting, every person in a QDA group can taste a sample of chocolate frosting individually and will all rate the frosting the same (for example, a 2.5 in creaminess on a scale from 1 to 5). You would ask questions about liking with QDA panel, but what’s cool is that (we’ll stick with the chocolate frosting example here) if you give them a frosting they’ve never tasted before, everyone in the group will still be able to give the frosting the same rating on the attributes they’ve trained for.