Bipolar disorder is a mental health condition that causes extreme mood swings that include emotional highs (mania or hypomania) and lows (depression). People with bipolar disorder experience periods of unusually intense emotion and changes in sleep patterns and activity levels, and engage in behaviors that are out of character for them—often without recognizing their likely harmful or undesirable effects. Bipolar disorder is often diagnosed during late adolescence or early adulthood and usually requires lifelong treatment.

Mania vs. Depression

Symptoms of the manic phase of bipolar disorder include feeling very happy or elated, feeling full of energy, being easily distracted, feeling self-important, being easily irritated or agitated, and not feeling like sleeping. People who are experiencing mania may become delusional and experience hallucinations and disturbed or illogical thinking. They may also do things that have disastrous consequences as well as make decisions or say things that are out of character and that others see as being risky or harmful.

Symptoms of the depressive phase of bipolar include feeling sad or hopeless most of the time, a loss of interest in everyday activities, feelings of emptiness or worthlessness, self-doubt, lacking energy, difficulty concentrating and remembering things, and suicidal thoughts.

Types of Bipolar Disorder

There are several types of bipolar disorder, including bipolar I disorder, bipolar II disorder, and cyclothymic disorder. Individuals who have bipolar I disorder have had at least one manic episode that may be preceded or followed by hypomanic or major depressive episodes. Individuals who have bipolar II disorder have had at least one major depressive episode and at least one hypomanic episode, but they have never had a manic episode. Individuals with cyclothymic disorder have had at least two years (or one year in children and teenagers) of many periods of hypomania symptoms and periods of depressive symptoms. Sometimes a person might experience symptoms of bipolar disorder that do not match one of these three categories, and this is referred to as “other specified and unspecified bipolar and related disorders.”

Comorbid Disorders

Fig. 1. BMC Psychiatry.

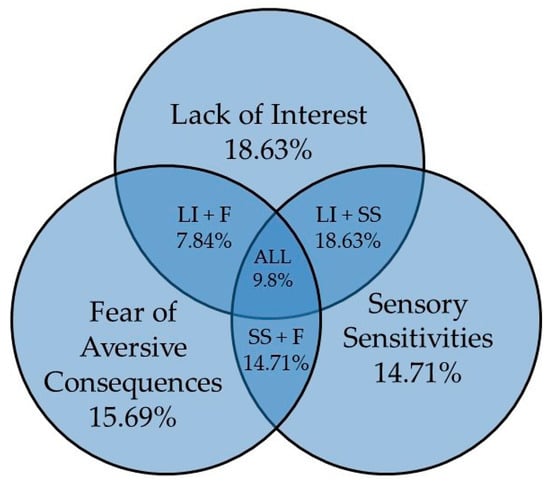

Many people with bipolar disorder also have other mental disorders or conditions, such as anxiety disorders, ADHD, substance use disorder, or eating disorders. Sometimes people who have severe manic or depressive episodes also have symptoms of psychosis, which may include hallucinations or delusions.

A 2022 study found that there is a high prevalence of medical disorders comorbidities in the group of patients that participated in the study. 96.3% of BD patients had at least one medical disorders comorbidity, and of the patients that had at least one comorbidity, 77% had two or more comorbidities (Fig. 1).

Bipolar Disorder Statistics

- Bipolar disorder affects approximately 5.7 million adult Americans, or about 2.6% of the U.S. population age 18 and older every year.

- More than two-thirds of people with bipolar disorder have at least one close relative with the disorder or with major depression.

- The median age of onset for bipolar disorder is 25 years.

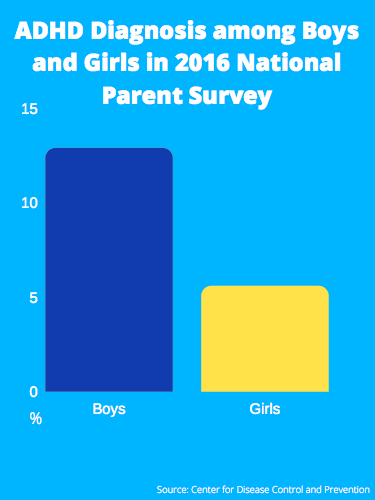

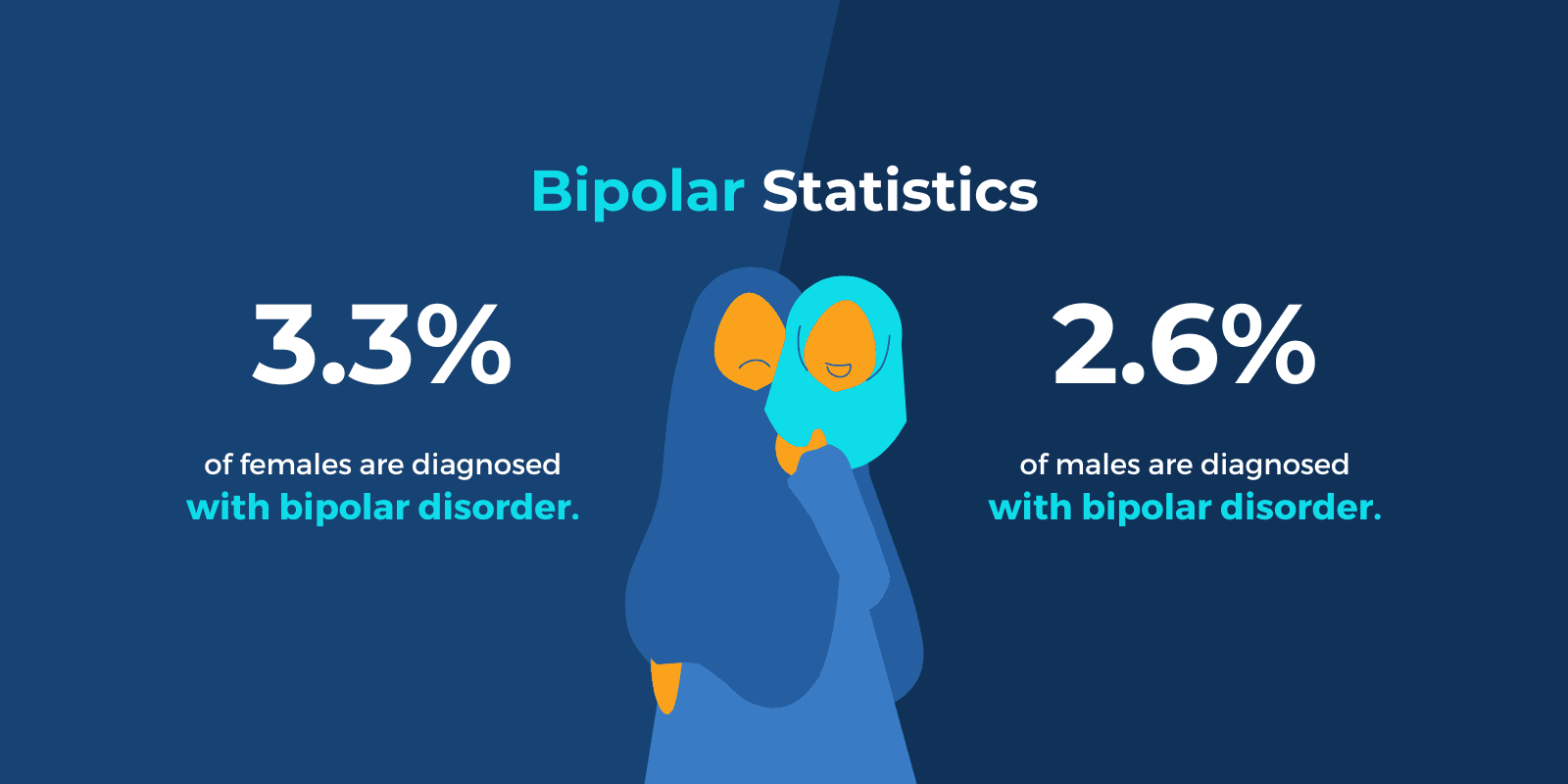

- Both men and women develop bipolar disorder, and only slightly more women are diagnosed than men (Fig. 2).

- Bipolar disorder is the sixth leading cause of disability in the world.

- As many as one in five patients with bipolar disorder completes suicide.

- When one parent has bipolar disorder, the risk to each child is l5-30%. When both parents have bipolar disorder, the risk increases to 50-75%.

Fig. 2. Sandstone Care.