Perfectionism would seem to be beyond reproach. It pervades everything from our legal system to our popular culture, structuring the promise of what we might become. But might it be an albatross around our necks–or, worse still, flatly incompatible with an ethical life?

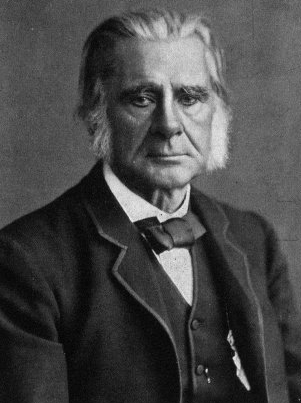

Thomas H. Huxley, Circa 1883, Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Should humans strive to perfect themselves and their civic institutions? At first blush, the answer might seem self-evident. Who wouldn’t want to eliminate all of our defects, along with their attendant vulnerabilities? And if one supplies the caveat that realizing total perfection is a pipedream, and we should, more modestly, just strive for perfection, in full cognizance that it will never be fully achieved, then the perfectionist proposition seems even more attractive.

Perfectionism is so deeply entrenched in cultural discourse that its invocation is bound to strike one as today as platitudinous. To the extent one hears the common anti-perfectionist refrain—“nobody’s perfect”—it is only to stipulate that nobody manifests or realizes perfection in actuality, not to contest its appeal as an abstract ideal.

Perfectionism is woven into America’s genealogy. The quest for perfection appears, dramatically, in the opening sentence of the United States Constitution: “We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union . . .” When in 2008 then-presidential candidate Barack Obama sought to set the Reverend Jeremiah Wright controversy in the context of the history of American racism, he proposed seeking national redemption through the concept of perfection: “The answer to the slavery question was already embedded within our Constitution—a Constitution that had at its very core the ideal of equal citizenship under the law; a Constitution that promised its people liberty and justice, and a union that could be and should be perfected over time.”

Given all of this enthusiasm around perfection, it might seem willfully dissentious to insist here that perfectionism exerts a potentially malign influence on ethics. Nevertheless, anti-perfectionism is the theme I want to take up.

The research conducted for my dissertation explores cultural, political, and aesthetic discourses during the nineteenth century that contested the use of perfectionism as an ethical ambition. I investigate why, in an era long understood to be obsessed with perfectionist striving, so many Victorians came to renounce the subjects of their veneration—indeed, renounce the goal of perfection altogether.

To its apostles, perfection was a beacon of hope in a world beset by anarchy. Waves of political unrest, trade-union strikes, hunger riots, cholera outbreaks, mass urbanization, rapid industrialization, and religious skepticism all contributed to an unsettling sense of a world wracked by unprecedented convulsions and spiraling toward cataclysmic destruction. As an organizing ideal, perfectionism held these fears at bay, recollecting disorder into a guiding vision of progress, stability, and completion. What concept could be more consoling, indeed more inspiring, than the prospect of transcending our defects and their attendant vulnerabilities?

To its detractors, though, perfection took on a far more sinister aspect. Perfection, anti-perfectionists warned, was a pernicious illusion, inviting a slew of invidious consequences that ultimately subverted the mostly laudable aims of its proponents. The imposition of an ideal of perfection cuts at the roots of liberty, spontaneity, and dynamic transformation, and at the same time breeds fanaticism and autocratic political configurations. But anti-perfectionists had a still more radical proposition, namely, that a full, flourishing human life need not be measured by its success in approaching perfection. They argued that meaning is deeply embedded in the experience of failure, suffering, and grief; that what is valuable is perceived, sensed, and felt through our provisional, animalistic bodies; that what is worthwhile may be radically incommensurable between separate persons. In short, they held that the value of a human life is inseparable from its imperfection.

But let’s return to the present for the moment. It turns out, in fact, that our popular culture is saturated with robustly articulated protests against perfection. Take, for example, the Borg.

Reproduction of an Assimilated Capt. Picard (Patrick Stewart), Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

First introduced on the second season of Star Trek: The Next Generation in 1989, The Borg would go on to become the most iconic villains throughout all the Star Trek’s television and film incarnations. Their single objective, ruthlessly pursued, is to achieve perfection. They do so by forcibly assimilating other species into their collective. Once individuals are assimilated, their knowledge becomes deposited into the hive mind, and every trace of their individuality and autonomy is erased. Assimilated persons are reduced to drones, who carry out the will of the collective with supreme efficiency and detachment. On TNG, Voyager, and First Contact, the Federation—the “good guys”—square off against the Borg by drawing on their unique talents as individuals, their emotional capacities (like anger and compassion), and their commitment to conception of human life with many diverse and discrete elements.

The Borg are drawn so as to cast the philosophy of perfectionism in a very ugly light. They show, for example, that a theory of justice that most efficiently maximizes what it sees as good may turn out to be a grotesque without a separate and sovereign account of rights. (This was the basis of John Rawls’ attack on teleological theories of justice such as utilitarianism.). Or, a regime that achieves unity by effacing the particularity of persons, and removes their ability to plan their own lives in accordance with their own evaluation of ends, may have an impoverished view of the value of autonomy. Or, finally, it may be that mechanization of life, though introducing manifold efficiencies into the means of production, may itself reduce the lives of the operators to extensions of their machines.

All of these incisive critiques, I want to point out, have their roots in the nineteenth century. Take the writings of the great English biologist Thomas Huxley. Remembered today as “Darwin’s Bulldog” for his full-throated advocacy of Darwin’s theory of evolution, Huxley wrote widely as an essayist on matters of comparative zoology. In “Evolution and Ethics,” he sketched a comparative analysis of the beehive and utopia. In the well-regulated apiarian society, Huxley finds an apt allegory for what he calls “the attempts to perfect society.” He explains,

The society formed by the hive bee fulfills the idea of the communistic aphorism “to each according to his needs, from each according to his capacity.” Within it, the struggle for existence is strictly limited. Queens, drones, and workers have each their allotted sufficiency of food; each performs the function assigned to it in the economy of the hive, and all contribute to the success of the whole cooperative society in its competition with rival collectors of nectar and pollen, and with other enemies, in the state of nature without. In the same sense as the garden, or colony, is a work of human art, the bee polity is a work of apiarian art.

Comprehensive, harmonized, purpose-driven, obedient to a matriarchal aristocrat—it is as though nature anticipated the perfectionist proposal and tested it out in nature. And so Huxley asks: If the apiarian society is perfection, would a self-aware, free agent choose to live in an analogous human society? If the answer is no, then this experiment has exposed something deeply unsettling about a well-ordered perfect society. Huxley points out that a hypothetical “thoughtful drone” would correctly conclude that the workers live “a life of ceaseless toil for a mere subsistence wage,” the result of “the perfection of an automatic mechanism, hammered out by the blows of the struggle for existence.” Holistic social perfection, no matter how harmonized or efficient, is profoundly unsatisfying in the absence of the capacity for choice. Among humans, the absence of “predestination to a sharply defined place in the social organism” means the social order will always be shifting, organic, and undefined, and the messiness of such a society is an indispensable feature of its attractiveness.

Katharine Hepburn in The Philadelphia Story, Courtesy of Wikipedia Commons

Another touchstone of anti-perfectionist pop culture is George Cukor’s The Philadelphia Story, the great 1940 romantic comedy starring Katharine Hepburn, Cary Grant, and James Stewart. The film became the vehicle for Hepburn’s comeback after a series of busts had led her to be labeled “box office poison.” It follows haughty Philadelphian socialite Tracy Lord (Hepburn) on the verge of matrimony with George Kittredge, a real man of the people who happens to be a great bore. Their nuptials hit a snag, however, with the arrival on the scene of her ex-husband (and recovering alcoholic) C. K. Dexter Haven (Grant) and tabloid magazine journalist Macaulay “Mike” Connor (Stewart).

On one level, the film is an ideological salve for the moneyed classes, rebutting the proposition that individuals are fundamentally shaped, for either good or ill, by their socio-economic class. Mike says as much to Tracy: “I made a funny discovery. In spite of the fact that somebody’s up from the bottom, he can still be quite a heel. And even though somebody else is born to the purple, he can still be a very nice guy.” The heel is Tracy’s fiancé, to whom she is to marry in a roughly an hour. The nice guy is, of course, her ex-husband, and the discovery of Dexter’s hidden virtues, notwithstanding his class affiliation, now authorizes him to (re)marry his beloved.

But this is only half of the pair. Tracy can only become eligible for her reunion with her ex-husband when she learns to surrender her self-regard as regal celestial being holding court for her admirers. As Dexter explains to Mike, “Strength is her religion, Mr. Connor. She finds human imperfection unforgiveable.” His direct address to Tracy is even more frank: “You’ll never be a first-class human being or a first-class woman, until you’ve learned to have some regard for human frailty. It’s a pity your own foot can’t slip a little sometime. But your sense of inner divinity wouldn’t allow that. This goddess must and shall remain intact.”

After a heavy night of boozing, Tracy learns that she does, in fact, have feet of clay. When her irate fiancé, under the illusion that she slept with Mike, condemns her and demands that she swear never to have another drink, she sees her own supercilious characteristics perched on a soapbox, and dumps him on the spot. In the final line of movie, Tracy’s father tells her she looks like a queen or goddess, and she replies that she finally feels like a human being.

The Philadelphia Story makes a serious indictment of perfection. The perfectionist dooms him or herself to the life a recluse, unable to accommodate or to forgive frailty in others. For Tracy, her perfectionism estranges her from her father and husband, and almost seduces her into moribund marriage—the fate that befalls perfectionist Dorothea Brooke in George Eliot’s Middlemarch (1871–72). Yet social isolation isn’t the worst problem. Rather, the allegation is that perfectionism makes a person ethically sterile and aloof from suffering. For the errors committed by the people she loves—her husband’s “deep and gorgeous thirst” for alcohol or her father’s philandering—Tracy’s response is simply to cut them lose. Intolerant of imperfection, she absolves herself of the responsibility to try to ameliorate the suffering of others. As a consequence, perfectionism does not function as incitement to transformation but a pretext to shirk her duty to others. Tracy’s final words to her husband—“Oh, Dexter. I’ll be yar now. I promise to be yar”—speaks to her new commitment to responsiveness and active compassion. She will no longer sit in detached judgment but attend to the needs of those whom she loves.

It turns out, then, that perfectionism has potentially invidious effects, and, further, that those invidious effects have been brought into aggressive visibility by both nineteenth- and twentieth-century fictional narratives. These narratives are worth revisiting as we scrutinize the purported allure of perfectionism.

Perfectionism also attacks people with disabilities.

[…] For the full post, see: Rock Ethics Institute | Anti-Perfectionism from Thomas Huxley to Star Trek […]