Sorcerer Mickey uses the broomsticks to help him clean while Sorcerer’s Apprentice by Dukas plays. Figure 1

Sorcerer Mickey uses the broomsticks to help him clean while Sorcerer’s Apprentice by Dukas plays. Figure 1

Throughout the course of this blog, we have focused on how film soundtracks define, conceptualize, and develop moods, places, and characters and their relationships. In the last post specifically, we talked about one of cinema’s best film composers, John Williams, and how he excellently captures human emotions in his scores. This connects to the larger idea that film music can create feelings, images, and concepts in films as well as form associations in a way that dialogue cannot. Like other art forms such as painting or dance, film music changes and redefines our perceptions of life and contributes to expanding our minds. Like nothing else, music interacts with our brains in many interesting and beautiful ways.

This brings us to today and our final blog post for the semester. In 1940, Disney’s Fantasia attempted something never done before. Instead of silly cartoons, fables, princess stories, or movie musicals, Disney took the most famous and emotive pieces of classical music and paired them with sometimes whimsical, sometimes beautiful, and sometimes frightening imagery. This included colorful fairies and mushrooms quietly moving through the night during Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker Suite (Video Link 1: Dance of the Sugarplum Fairy), Sorcerer Mickey desperately trying to control disobedient broomsticks during Dukas’s Sorcerer’s Apprentice (Video Link 2: Sorcerer’s Apprentice), and unicorns and satyrs dancing during Beethoven’s 6th Symphony: “Pastoral” (Video Link 3: Pastoral (partial)). These cartoons tell stories conceived from the emotions that cartoonists felt and from the images their brains formed while listening to the music. The music could conceive unique narratives in each cartoonist’s mind.

The film’s first piece, Toccata and Fugue in D Minor by Bach (Video Link 4: Toccata and Fugue), shows how listening to music can react in our brains through abstract imagery. Different colors, shapes, lines, and scenes appear in different contrasts and designs throughout the song. In addition, the seamless transition between the toccata and the fugue at 3:38 changes from showing the band in different lights and colors to more abstract shapes. Mesmerized and relaxed, the viewer becomes enthralled in the song and experiences an intense and cohesive auditory-visual experience. Without any dialogue or concrete imagery, Fantasia is able to capture the audience and engage their minds.

One of my favorite sections from Fantasia is the Rite of Spring by Stravinsky (Video Link 5: Rite of Spring). In Disney’s interpretation of the song, the viewer follows the creation of the universe and the evolution of life up through the time of the dinosaurs. The section ends with the meteor causing their extinction. There are calm and eerie parts in the ocean, loud booms of volcanoes, and even a terrifying T-Rex scene that horrified me as a child. The music suits the visuals very well, but interestingly enough, the evolution of life was not the original concept for this song. Stravinsky wrote this song to tell the story of Native American tribal rituals. The booms were supposed to represent the rattling tribal drums and the terrifying rising action was the human sacrifice of a young girl. These two very different but fitting interpretations of the same set of sound waves shows how interpretative and emotional music can be.

Soundtracks can contextualize and define their films. Whenever I listen to classical music, I imagine a story forming, I feel a tightness in my chest and need to take deep sighs, and I get shivers down my spine. Music can interact with our minds in ways that words cannot. For example, when I listen to Moonlight Sonata by Beethoven, I imagine the movements cohesively and methodically developing a story. Though we are simply listening to different combinations of sound waves, I imagine the first movement panning through the dark and mysterious night with bugs, raccoons, and owls under the moonlight. In the second movement, we go through a window into a lively Regency-period ball. The gentlemen and ladies dance and drink in merriment. During the ball, a young man and woman meet and it’s love at first sight. However, after an enchanting evening, another man tries to earn the woman’s attention and she changes her mind, choosing this new man instead. In the third and final movement, the original young man is devastated as his enchanting love has been stolen away. After the ball, he races on horseback to catch his love and her new beau in their carriage, while suppressing his instinctual desire to kill the other man. He becomes disturbed and enraged trying to hide the madness he feels in his heart, and by the end, in total insanity, he shoots the man and collapses, only to be found by his now-horrified love. This may be an odd or strange interpretation to a listener; they may see this song in a completely different way, but nonetheless, this is how I feel the song. The cartoonists of Fantasia also felt the songs of the film and interpreted stories, characters, and designs.

The Pegasus family flies through the sky to the beautiful 6th Symphony: “Pastoral” by Beethoven. Figure 4

The Pegasus family flies through the sky to the beautiful 6th Symphony: “Pastoral” by Beethoven. Figure 4

Throughout the semester, we have subjectively interpreted the sound waves that we heard during each film. In the Baby Driver posts, we talked about the Romeo and Juliet star-crossed lovers archetypal relationship between Debora and Baby. The song Brighton Rock by Queen helped to bring out the complexity of their relationship and show its turmoil. It was difficult to define their relationship and their emotions in words, so I posted Brighton Rock instead so that you too could feel their turmoil. In the John Williams post, we discussed the pure joy and childhood wonder found in the score of E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial. When I hear the bike chase scene music, I shed a few tears because of the way I feel when listening to the music. We have been subjectively interpreting music all semester.

Thank you so much for reading the blog this semester! It’s been a joy to write about my favorite films and composers. Music really means so much to me and I hope that I have expanded your understanding of soundtracks and perhaps opened your minds to new possibilities and perceptions.

Image Credits:

Figure 1: Image 1

Figure 2: Image 2

Figure 3: Image 3

Figure 4: Image 4

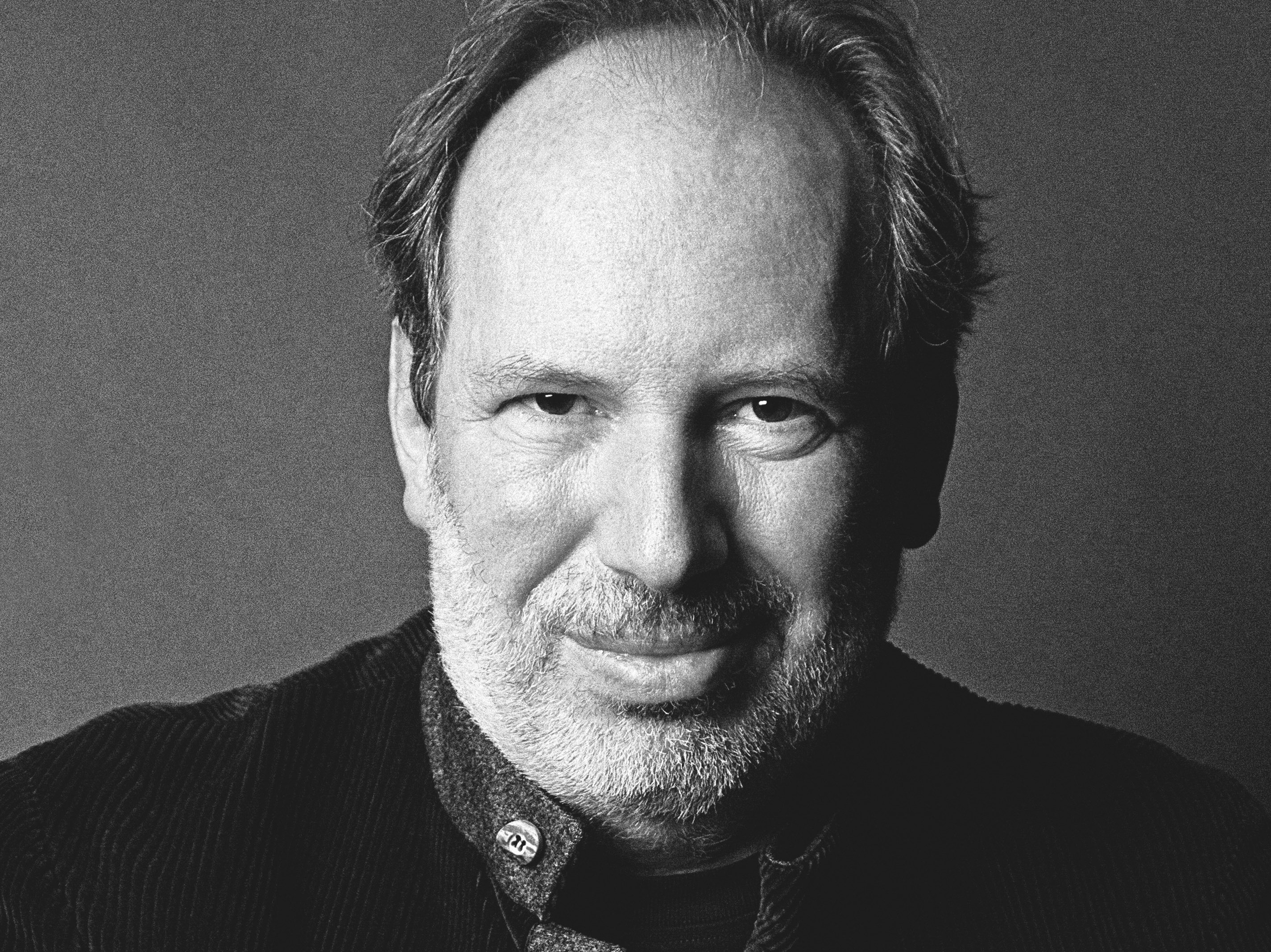

. The Greek composer Vangelis poses for the photo in his studio around the time that Blade Runner was scored. Figure 3

. The Greek composer Vangelis poses for the photo in his studio around the time that Blade Runner was scored. Figure 3

Debora and Baby (played by Ansel Elgort) talk together in the diner as Debora takes Baby’s order. Figure 2

Debora and Baby (played by Ansel Elgort) talk together in the diner as Debora takes Baby’s order. Figure 2

After an illegal weapons deal gone wrong, the heist team sits in the diner where Debora works. Figure 4

After an illegal weapons deal gone wrong, the heist team sits in the diner where Debora works. Figure 4