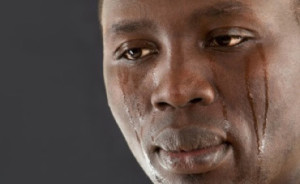

Most people would tend to agree that crying is not a very fun act. But I don’t thing that most people could tell you the first scientific thing about it. First of all, what even are tears? I heard someone say the other day, “it’s like sweat from your eyes.” I am pretty sure that is not true, but in order to know for sure, I wanted to research what tears are made of and try to understand if scientifically crying can make you feel better. First things first, what are tears?

Types of Tears

According to howstuffworks.com, tears are made of protein, mucus, water, and oil combined to make a salty liquid. Chip Walter writes in his article, there are three types of tears: Basal, Reflex, and Emotional. Basal tears are the ones that coat your eye every time you blink keeping it moist. Reflex t ears clean out the eye when it is poked or something gets in it, like dust or onion fumes. Emotional tears are the third kind, which have a genetic make-up that is entirely original. According to William H. Frey II (Biochemist at the University of Minnesota), emotional tears “carry 20 to 25 percent more types of protein and have four times the amount of potassium than reflex tears.” You may not be surprised to learn that emotional tears carry great amounts of hormones, like ACTH, which is produced when a person is under immense stress or prolactin, which controls the glands that release tears. Women tend to have higher levels of prolactin in their body, which may explain why they tend to cry more then men (Walter).

ears clean out the eye when it is poked or something gets in it, like dust or onion fumes. Emotional tears are the third kind, which have a genetic make-up that is entirely original. According to William H. Frey II (Biochemist at the University of Minnesota), emotional tears “carry 20 to 25 percent more types of protein and have four times the amount of potassium than reflex tears.” You may not be surprised to learn that emotional tears carry great amounts of hormones, like ACTH, which is produced when a person is under immense stress or prolactin, which controls the glands that release tears. Women tend to have higher levels of prolactin in their body, which may explain why they tend to cry more then men (Walter).

Why do we cry?

The Good:

Because of the amount of hormones released when emotion tears are discharged, William H. Frey II explained that it is good to cry in order to flush out the chemicals involved with strong feelings of stress or sadness. But it is a controversial topic among many scientists. Some believe that the tear duct is not big enough to release the amount of hormones needed to bring a persons hormones back to their natural balance. In that case, some believe there is another mechanism that leads to relief after a good, long cry. Some suggest, “perhaps we do not cry because we are upset but because we are tying to get over being upset.” Do we cry because we are trying to settle down to prevent future emotional and hormonal damage from stress? The answer is still unknown to this question, many scientists have tried to explain certain aspects of why we cry (Walter).

amount of hormones needed to bring a persons hormones back to their natural balance. In that case, some believe there is another mechanism that leads to relief after a good, long cry. Some suggest, “perhaps we do not cry because we are upset but because we are tying to get over being upset.” Do we cry because we are trying to settle down to prevent future emotional and hormonal damage from stress? The answer is still unknown to this question, many scientists have tried to explain certain aspects of why we cry (Walter).

Some people in Japan believe in the benefits of crying so much that they go to a crying club, in which they watch sad documentaries in order to feel relief.

The Bad:

But what is the other side of the argument? According to this article, “A “good cry” can make you feel better [but] a bad cry can make you feel worse.” A good or bad cry is measured using many different aspects of the cry. For example, the goodness of the cry can depend on when it happens, who the person is with, and where it happens. If there is support from the audience around the crier, it is much more likely the person will feel better. On the other hand, according to a 5,000 person study complied of men and women, those who felt unsupported or tried to suppress the cry in any way explained that they felt worse after. There have also been studies done on how tears can negatively effect those in a depression

state and in those how have difficulty expressing their emotions.

The Ugly:

A few scientists like, Amotz Zahavi (a biologist at Tel Aviv University), Dario Maestipieri (a primatologist at the University of Chicago, and Randolph R. Cornelius (a psychology professor at Vassar College), explain that humans cry because they want to communicate emotions to others. We as humans know that if someone is crying they are usually upset and these scientists believe that we cry to warn other people or to project vulnerability. It is also said that people (especially women) cry for attention or manipulation.

Based on research, most scholars believe that the only downside to crying is not doing it. Trying not to cry can build up any stressful and unfriendly emotions that will almost always come back around later. This act also can effect physical health, with the release of many hormones building up in the body.

The Bottom Line: Researches have found that crying is beneficial to a person’s health and the only harm that can come involving crying is suppressing tears, which can cause physical and emotional harm to the body.

Sources (that don’t work as hyperlinks because they are from the library):

Walter, Chip. “Why Do We Cry?” Scientific American Mind 17.6 (n.d.): 44-51. EBSCO Host. Web. Sept. 2015.