Through elementary and middle school I used to play three instruments. The idea that people who play musical instruments have better cognitive function compared to those who don’t interested me. I read an article that explains that playing an instrument involves both your central and peripheral nervous systems and makes brain precisely process auditory, sensory, visual, and emotional information. The ability for the brain to process this information depends on neurons which communicate to each other by firing electrical impulses, also known as brainwaves. Nina Kraus, a neurobiologist, describes how these brainwaves can be used to evaluate how the brain processes pitch, timing and timbre(components of music).

In two studies MRI’s were able to show how the structure of people’s brains who play an instrument change. In the first study an MRI was taken of people who practice piano on a regular basis in comparison to those who don’t. The MRI showed that the musicians had a greater structure of white matter; this is interesting because people who have amusia (tone deaf) lack a consistent structure of white matter. In anotherstudy conducted in 2003 by Gottfried Schlaug and Christian Gaser it was found that the amount of gray matter in auditory, motor, and visual regions of the brain was different between high- practicing musicians, low-practicing musicians, and people who have never played an instrument. The differences had a p value of less than 0.05, therefore, the results show that something is going on. The researchers also found that there was a greater volume of grey matter in the cerebellar cortex of high-practicing musicians, which is important in cognitive learning and music processing. This difference also had a p value of less than 0.05, so the null hypothesis can rejected. The researchers discuss that since they were able to find multiple structural changes it is not likely that they occurred naturally and that more studies are needed.

In 2012, a study performed by Hanna Pladdy evaluated how practicing a musical instrument, for more than 10 years, could improve cognitive function later in life. Pladdy describes that since it was impossible to control the participant’s daily activities it was hard to differentiate if the cognitive changes were due entirely to musical training. There were 70 participants (59-80 years old) divided into musicians who had 10+ years of musical training and non-musicians. She found the musicians scored higher in tests that involve verbal  and motor skills. Additionally, Pladdy found that those who started practicing before the age of 9 had increased verbal <a href=”http://www.wisegeekhealth.com/what-is-verbal-working-memory.htm#didyouknowout”>working memory</a>in adulthood. She also suggests that beginning training at a young age and practicing for at least 10 years could make up for less education; the participants who showed the greatest differences had received less education. The study had a low number of participants so the results are not that reliable, however, they provide evidence that something is going on.

and motor skills. Additionally, Pladdy found that those who started practicing before the age of 9 had increased verbal <a href=”http://www.wisegeekhealth.com/what-is-verbal-working-memory.htm#didyouknowout”>working memory</a>in adulthood. She also suggests that beginning training at a young age and practicing for at least 10 years could make up for less education; the participants who showed the greatest differences had received less education. The study had a low number of participants so the results are not that reliable, however, they provide evidence that something is going on.

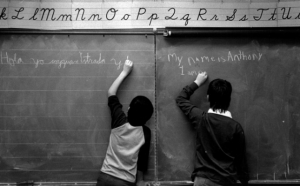

A subsequent experiment, published in the Journal of Neuroscience, conducted by Nina Kraus in Los angeles evaluated the effect of the Harmony Project (a non-profit organization that provides music lessons in low-income areas). Kraus explained that, in general, children in low-income areas have a harder time discriminating consonants because statistically by the age of five they are exposed to fewer words than other children. Kraus conducted a randomized unblinded controlled trial by randomly dividing the kids on the waitlist for the program into two groups. The first group would be tested after taking 1 year of lessons and the second group would be tested after two years of lessons. The results showed that the brain processing for children in the second group became more precise and the brain was able to process consonants faster and more efficiently;therefore school and daily life would become easier. Kraus acknowledges the problems with this study since only children ages 6-9 were used and it was not performed in a control lab setting(no way to know if outside activities the kids were engaged in were the reason for their improved cognition).

Although the studies some flaws whether it be small participant groups or an inability to evaluate confounding variables, I think that the results show evidence that this question should be evaluated further. None of the studies were able to reach a clear conclusion, however they were all published which shows that the researchers believe that the findings are big enough to be studied further. So do people who play instruments have a better cognitive ability? I can’t say yes or no, but it can’t hurt to start up a new hobby.