I just learned the last post was my 200th SC200 post. That’s 40 a year.

Monthly Archives: December 2014

Of professors and physicians

There is an in-built confirmation bias in medicine. If the patient gets better, doctor assumes s/he healed the patient. If the patient dies, doctor assumes the patient was really sick and beyond help. This bias means doctors have gone on with useless or even harmful practices for years (or even centuries).

There is an in-built confirmation bias in medicine. If the patient gets better, doctor assumes s/he healed the patient. If the patient dies, doctor assumes the patient was really sick and beyond help. This bias means doctors have gone on with useless or even harmful practices for years (or even centuries).

Pondering the SRTE‘s, I suddenly realized I was thinking just the same way: when students said they learned things, I attributed that to my fantastic pedagogy. When students said they learned nothing — or worse, showed me that they learned stuff that was wrong — I assumed those students hadn’t come to class, or didn’t listen, or were unteachable…

Pondering the SRTE‘s, I suddenly realized I was thinking just the same way: when students said they learned things, I attributed that to my fantastic pedagogy. When students said they learned nothing — or worse, showed me that they learned stuff that was wrong — I assumed those students hadn’t come to class, or didn’t listen, or were unteachable…

Mmmm…. Well, Andrew, follow the logic you taught in class…

Ok. For sure, customer satisfaction surveys could not get medicine out if its confirmation bias. So SRTEs can not get we professors out of ours. What’s needed instead is the equivalent of the randomized control trials which frequently save medicine from itself (or more correctly, save patients from the practitioners). I need to enroll a class and then at the last minute, refuse entry to a randomly chosen half of the students so they go off and do another course. Which group would go on to best achieve the course objectives?

The endpoint of such a study is not easily defined, let alone measured. Performance on the final exam is irrelevant (and is in any case a softer-than-soft endpoint). The real test is whether a difference could be detected years later, long after graduation.

Good thing we can’t do that experiment.

What are the most important things you learned?

My other favorite answers to this question on the 2014 course evaluation questionnaire (excluding those similar to the 2013 answers):

- I now have an understanding of what contributes to global warming

- I learned how to think harder than I ever had to before

- I learned to question everything

- I learned that science does apply in real life, who knew?

- Scientists and science can actually be interesting to learn about and discover

- Some of the things you wouldn’t think were science actually are

- how to connect information learned in class to everyday occurrences/news outside of class

- I realized I do not despise science as much as I thought

- the difference between science and faith

- Risk evaluation. Seriously, I’ll stop fearing drowning in a pool or dying in a plane crash

- don’t accept something just because it is ‘established’

- our intuition is lousy

- I learned specifics on things that are normally not given a second thought e.g. how we learned smoking is bad for you, how vaccines work etc.

- How negative science is

- That not all science is dull

- Science is beyond the normal science classes most of us are used to

- Animals can be gay and aliens most likely exist

- The difference between x and y.

- I learned I actually enjoy science!

- do not believe everything you read in the media.

Those comments, like last year’s, make me glad I teach this course rather than teaching biology to biologists, important though that is. This feels much more impactful.

By way of balance, lessons the students learned that I worry about:

- We know nothing about the world and science is entirely theories that are either correct or wrong, but we’ll never know if it is or not because nothing can be proven correct, so it all seems kinda pointless

- I am not a science major I will never be a science major I now never plan on being a science major

- I didn’t learn anything

Most concerning of all was the comment: The Australian accent is charming. If the SRTE‘s weren’t anonymous, that student would be a straight fail.

"Science isn't only for scientists"

That, my favorite student response to the course evaluation question What have you learned?

The responsibility

For the first time, this year’s class was almost entirely first semester freshmen. Much to my surprise, I felt an immense responsibility to set these students off on their Penn State careers the right way. That meant trying to impart more than ‘just’ course-related skills like critical thinking, the evaluation of evidence, distinguishing a reasoned argument from baloney, and empowering students to question what they hear from professionals, professors, peers and parents. It meant trying to get across additional things like study habits and time management, honesty and integrity, the ability to learn from failure (or low grades) and the importance of class room discipline. In email correspondence, it often also meant advocating the merits of developing a decent work ethic; or put another way, how to get an A without trying to bullshit or bully the professor.

How well did I do on any of that? I’m not sure. There were signs of serious integrity-failures. There were three plagiarism cases, despite my best efforts; I hope I handled these in a way that taught the students to never do it again but without my ruining their College careers from the get-go. I was ruthless on people who missed deadlines. I talked endlessly about the need to manage time. I am not sure if that worked. Many still left their blog posts to the last minute and it showed, just as I told them it would. I talked of the benefits of attending the voluntary review sessions. Most did not bother. I implored students to come to class and played with attendance grade algorithms to try to make that happen (I’ll evaluate whether that worked in forthcoming post). I stood up to the pleas, begging, and bullshit demands for a higher grade. I truly believe students need to earn their grades. Anything else cheats them (for the most part, life is not like that) and all those others who work honestly and hard. But I also tried to be sympathetic when students with dire personal problems reached out. It’s amazing how a little understanding from faculty, the right word at the right time, can transform a life’s direction.

How well did I do on any of that? I’m not sure. There were signs of serious integrity-failures. There were three plagiarism cases, despite my best efforts; I hope I handled these in a way that taught the students to never do it again but without my ruining their College careers from the get-go. I was ruthless on people who missed deadlines. I talked endlessly about the need to manage time. I am not sure if that worked. Many still left their blog posts to the last minute and it showed, just as I told them it would. I talked of the benefits of attending the voluntary review sessions. Most did not bother. I implored students to come to class and played with attendance grade algorithms to try to make that happen (I’ll evaluate whether that worked in forthcoming post). I stood up to the pleas, begging, and bullshit demands for a higher grade. I truly believe students need to earn their grades. Anything else cheats them (for the most part, life is not like that) and all those others who work honestly and hard. But I also tried to be sympathetic when students with dire personal problems reached out. It’s amazing how a little understanding from faculty, the right word at the right time, can transform a life’s direction.

The most useful question on my SRTE questionnaire is: What three things have you learned? In terms of these non-content ambitions for the course, here’s what students’ said they’d learned.

- time management [several comments along these lines]

- I learned how much better my learning experience is by being mindful of people around me

- don’t sit by someone who talks

- the impact of talking in class

- read the questions in tests carefully

- Andrew isn’t as scary as he seems

- better note taking [several comments along these lines]

- how to blog better [many comments along these lines]

- writing takes practice [oh so true!!]

- the importance of having an engaging instructor who was willing to help and wanted his students to succeed

- the importance of avoiding procrastination

- learn from mistakes

- different study methods

- always go to class [many comments along these lines]

- pay attention and listen to what the Professor says

- I learned to write better

- that it takes work to improve your grades

- that its ok to need help but you aren’t going to get it unless you ask (the revision sessions proved this)

- improvement is key if you want to learn

- how to right (sic) fantastic blogs

- don’t just focus on the examples, but the concepts within

- the importance of getting help when you need it instead of sitting around watching your grade plummet

- take advantage of the TAs [I assume this is meant in a good way…]

- the importance of weeding out people who are talking in class at the beginning of semester [said as a criticism of what I did not do well enough]

- 1. I will not automatically succeed. 2. If I put in the work, I will succeed. 3. I don’t need 8 hours of sleep.

Most of which is gratifying. But from the responses to the question ‘What changes would improve your learning?’, it is clear I have some way to go on getting students to seize control of their own learning. That’s surely one of the most important life skills we need to get across in Higher Education. After graduation, it’s rare to have someone offering homework or review sessions or changing the algorithm to suit your time management ability. But in meaningful work and for a meaningful life, learning remains critical — indeed it might be more critical than at College. How do we better encourage students to self-teach?

The student evaluations….

Course and faculty evaluations come mainly in the form of Student Rating of Teaching Effectiveness. This year, my scores are up by 0.2-0.5 units (on the 7 point scale), reversing the general decline I’ve experienced over the last few years. Since I can not standardize myself (I hope I change), I bench mark the whole thing to the otherwise very dull question of the clarity of the syllabus (my syllabus is the same each year). I think of this as a measure of class orneriness. Syllabus clarity got a mean score of 6.22, up from the 5.75 of last year. So I guess the class of 2014 was 8% less ornery than last year. But since that jump was one of the biggest, it might mean that in real terms (i.e. orneriness-adjusted), the class is actually a little less satisfied than last year.

Course and faculty evaluations come mainly in the form of Student Rating of Teaching Effectiveness. This year, my scores are up by 0.2-0.5 units (on the 7 point scale), reversing the general decline I’ve experienced over the last few years. Since I can not standardize myself (I hope I change), I bench mark the whole thing to the otherwise very dull question of the clarity of the syllabus (my syllabus is the same each year). I think of this as a measure of class orneriness. Syllabus clarity got a mean score of 6.22, up from the 5.75 of last year. So I guess the class of 2014 was 8% less ornery than last year. But since that jump was one of the biggest, it might mean that in real terms (i.e. orneriness-adjusted), the class is actually a little less satisfied than last year.

Or it might mean that I am making WAY too much of these scores, which above a certain threshold (4?), really should be taken with a pinch of salt. It’s the comments the student’s write that are valuable.

When I started the course in 2010, I wanted to hear what all the students thought, so I bribed the class with extra credit if they could get an SRTE return rate of over 85%. This resulted in my course getting one of the highest return rates on campus (c. 90%). This year I decided to do away with the bribe. That resulted in a 47% return rate. I thought the rate would be lower, especially since I only urged the students to do the SRTEs once, and then to a class room near half empty. Staring at the numbers and the comments, I don’t see any major differences from previous years. I guess the motivated and the disgruntled do the STREs whatever; I assume the missing 40% had nothing much to say. In fact, in the spirit of Christmas good cheer, I will assume they were all neutral to moderately happy. The group I’d like to have heard from were the 12 who dropped the course. They never tell you why. I hope it was not to do with me or SC200.

My own feeling is that students can’t really assess how valuable a course was, or how good their teacher, until many years later. That’s particularly so for Freshmen in their first semester. I’d love to hear from any of them as their Penn State careers progress. Better yet, after graduation. Cocktails in Zolas anyone? What was good? What could I do better?

My own feeling is that students can’t really assess how valuable a course was, or how good their teacher, until many years later. That’s particularly so for Freshmen in their first semester. I’d love to hear from any of them as their Penn State careers progress. Better yet, after graduation. Cocktails in Zolas anyone? What was good? What could I do better?

The bottom line for 2014

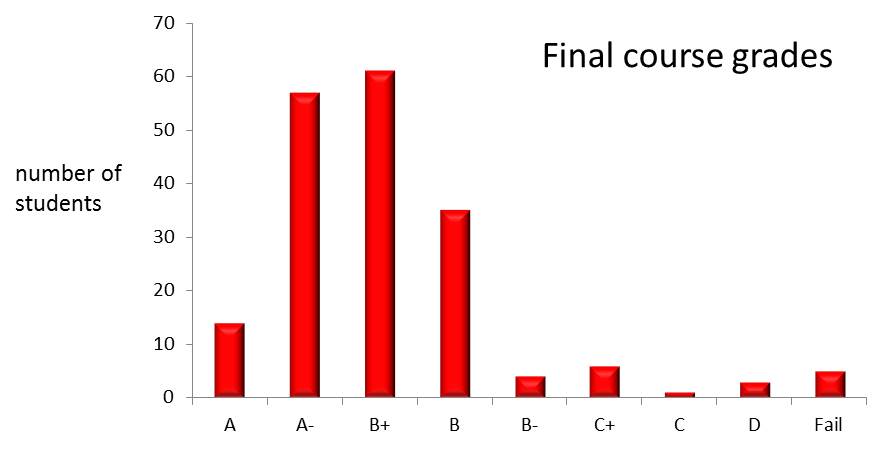

The class average: 88% (B+). Four of the 14 students with an A are four scored >100% through extra credit. In the absence of extra credit, the highest score would have been 98%.

Of the 198 students who started the semester, 186 made it to the end in the sense of getting a grade for the course on their transcript. Of those 186, 38% got some kind of an A, 71% got a B+ or better, and 90% of students got a B or better. Compared to last year, fewer A’s but way more A-‘s and B+’s. This despite the fact that this year I abandoned the non-merit based extra credit I uneasily dispensed in previous years.

It is difficult to calculate the impact of my final exam cock-up. It looks to me like one person passed who might not have otherwise done so, and undoubtedly some others went a grade higher than they deserved (Merry Christmas). But not many. The difference between the 100% I gave out and the 80-85% that would likely have been the class average exam score is 15%. The exam is worth 20% of the final grade – so the average contribution of my largess is just 3%. Not much in the scheme of things, and less than bribery I used in previous years to encourage students to come to class and fill out the end of course questionnaire. And like that bribery, the cock-up gave me a grade buffer. I could say to students wanting me to bump them up a grade that they were only close because of my mistake.

Of course, there is simply no way to know what to make of this grade distribution. Am I setting the bar too low, too high or just right? It is one of the mysteries of high education.

The final exam 2014: FUBAR

I let students have two goes at all the class tests and the final exam. I get the on-line system to tell the students how well they did after the first go, but nothing more. This means they do the test again thinking even harder. I like that: the aim of my tests is to teach (assessment is a very very secondary aim). The students like it too: they think having a second go helps them (though the reality is that their scores are as likely to go down as up). This two-shot strategy has worked really well for the 24 class tests and final exams that I have previously run. But this time….

The course management software (Angel) returns the answers as its default position. In the end-of-semester chaos, I forgot to flick the switch that stops that… And I never noticed because Angel doesn’t let you pretend to be a student doing the test ahead of time: you can only get the student view in real time. And I did not have real time.

I was at a conference in Thailand, jet lagged. I got to do the test eight hours after it went live and just a few minutes before I was due to give my keynote talk. I immediately saw the problem (oh that sinking feeling). But by then, about 15 students had done the test. Naturally, most of them had got 100% on their second go (although my favorite exception was the first student: from 46% to 93% [93%?]). I realized immediately the test was a blow out. If I switched off the answers there and then, what to do about those 15 students? I debated calling the whole exam off but decided that most of the students would have a proper go the first time, and so learn something. But as an assessment, it was clearly blown. I would have to give everyone who did the exam 100%. Which I duly did.

The fiasco generated an interesting study in humanity. Of the 181 students who did the final exam, just six emailed to point out the problem. (To put that in perspective, four other students emailed to complain about their blog grades during that same period.) One of the six covered herself in glory. She emailed me, a TA and my staff assistant to point the problem out – and then deliberately did not use the right answers before her second go. Another of the six (one of this year’s blog plagiarists) used the answers to elevate her score to 100%, and then asked for extra credit for bringing it to my attention.

Among the other 175 students, there were 15 who got all questions correct on their first and only go. It is possible that they genuinely achieved 100% through their own efforts. If so, I hope those students took great satisfaction. But on none of the previous tests did anyone get everything right, let alone on their first go. Hard to think the list of answers wasn’t floating around the class, despite the honor pledge. It’s no wonder there is so much corruption in society.

Still, no getting round it: what a cock-up on my part. Apologies folks.

Talking like an American

I think my charming New Zealand accent is becoming more Americanized. I now pronounce schedule as skedule and route as rout because I know from experience that Americans get really distracted if you don’t say it their way (try asking for tune-a instead of toona at Subway, or for a croissant at Panera pronouncing croissant the way the the rest of the world does). While I joke about my accent to break the ice early on in the course, it matters a lot in class because I really don’t want students distracted from the main message by something tangential like the way I say things. And my choice of vocabulary can affect comprehension a lot: crib death is cot death to me, and cow pies are cow pats (who in their right mind would talk of cow excrement as if it was edible?). But I continue to learn. Words this year that attracted attention:

walrus (woolrus)

walrus (woolrus)

condom (condim)

albino (al-bean-o, al-by-no)

urine (u-rin)

Monty (Mony)

do do (poop)

Duke (dook)

advertisement (adver-ties-ment)

yo-gurt (yog-urt)

snog (snog)

[actually I think there is only one way to say snog, but a Professor saying snog is novel]

China (?Beats me why someone posted to the comment wall asking me to say China again)

But the best of all was the distinction I got repeatedly asked about: review sessions versus revision sessions. To me the words are interchangeable, and they have been during the previous four SC200 classes. But no longer. It turns out this is a rare example of American-English being more nuanced than English-English. I have now learned that review sessions are where you go over things and revision sessions are where you change things. Apparently my advertising what I will from now on call ‘exam review sessions’ as ‘exam revision sessions’ got some hopes up. Live and learn.

Overall Class Test grade 2014

There are four class tests during the semester. I take the average of the best two as the final test grade. This allows students to improve. Improvement is of course the aim of education. It also eases complaints and fear. For many of the students, their grade on the first class test was their first C or D ever.

The breakdown for the overall test grades for 2014: A, 23 (including two with 100%); A-, 55; B+, 21; B, 29; B-, 27; C+, 13; C, 8; D, 8; Fails, 2.

Interestingly, that means 42% of the class got an A of some sort. The corresponding figure for the blogs is 16%. So despite the endless complaints that my tests are too hard, people actually do better on the tests than on the blogs. I hadn’t thought of that before, but looking at it, I see that was also true in previous years (e.g. 2013 blogs, 2013 class tests). So there is more scope for improvement with the blogs. That’s especially interesting since they can be done any time, on anything, under no time pressure, no exam freak-out scene, with endless help freely available from the TAs and with lots of personalized feedback from the graders….

Memo to self: make sure you mention this to the class next year.