Let’s talk about salmon!

While, at first glance, I know that this may not seem like the most interesting topic, it is an important one, nonetheless. There are several types of salmon. Luckily for us, there is an easy pneumonic device I learned in Alaska to learn them all. Most people have 5 fingers on their hands which correlates to the 5 different types of Pacific salmon. The pink salmon goes with the pinky finger, Silver salmon to your ring finger (as in silver rings or jewelry, Chinook or king salmon for the middle finger (since it is the largest), sockeye for the pointer ( since it is the most versatile and abundant), and chum salmon which, like the thumb, is often taken for granted.

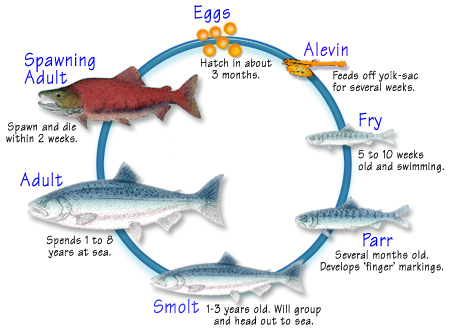

These types of Pacific salmon start their life cycles in freshwater runs in the inland portions of Alaska and Canada. For the first portion of their life cycle, they need to remain buried in undisturbed gravel for several months. During this time, the salmon roe is incredibly vulnerable to climate catastrophe or predation. In addition to that, salmon nesting sites are perennial and have been the same for hundreds of generations of fish. So much so that many Indigenous cultures have arisen alongside salmon runs.

Salmon has a long and important history of being a valuable economic and cultural commodity for Coastal First Nations people. In the legend of the Salmon People, a Salish First Nation creation story, ” is told by many First Nations cultures and these stories helped shape the traditions and lifestyles that were passed down from one generation to the next,” as described by Indigenous Author, Donna Joe. Throughout the year, several festivals are held to honor the life that salmon have given to their people, with the Kwakwaka’wakw holding one of the largest festivals at the start of each salmon run season. In addition to their cultural significance, salmon was one of the main food sources to these people before the land was colonized. According to the University of British Columbia Indigenous Foundation, First Nations people set up sustainable farming methods that included fish censuses and an International network of knowledge, ceremonial redistribution, and trade.

With the arrival of North American colonizers, The United States Department of Fisheries and the Canadian government created laws and regulations that prevented Indigenous communities from practicing their traditional fishing methods, most notably, the creation of The Aboriginal Food Fishery in 1880, which put major barriers in place for Indigenous people to fish for their own food (while expanding commercial fishing). Under The Fishing Regulations Act, this organization also required Native People to apply for licenses and permits to fish for salmon- which they had already been doing for centuries. While this ruling hand been overturned in the Canadian Supreme court in 1992, the damage had already been done. Over 3 generations of First Nations people had lost connection with this part of their culture and heritage.

While governmental organizations have been trying to rectify their unjust actions against First Nations people (with respect to their traditional practices with salmon alone (considering in Canada, there is an ongoing genocide against Indigenous women)), there is still a large inequitable gap in circumstance and privilege. Bound by unwilling treaties, Native tribes are forced to carry the weight of salmon conservation efforts. As per historic mandates, Native fisheries are only allowed to hunt in specific areas, while commercial fishermen can fish in most areas with a permit. As described by the Northwest Indian Fishing Committee:

“Loss and degradation of habitat is the primary reason salmon have declined and continue to stay at low numbers, despite efforts to restrict harvest. Instead of dealing with the real factors leading to the decline of salmon, much focus has been put on restricting {Indigenous] fisheries.

There is no difference between a salmon that has been harvested and one that fails to survive because of habitat loss and degradation. Both are dead.”

Native communities have seen more than an 80% decline in their fishery population in the last two decades, with many populations disappearing entirely. In addition to global oceanic acidification and warming waters, Alaskan and Canadian salmon have become a massive international export, with the demand for wild-caught salmon well exceeding the supply. In addition to a thriving black market for wild-caught salmon, the voices of First Nation people have been systematically silenced.

When a tribe’s salmon run is destroyed by climate change and corporate greed, their local food source and economy are not only being destroyed, but a piece of their culture is lost too. And all of this is not to say that there is no hope, but there is. A breakthrough study conducted by Dr. Will Atlas, Watershed Scientist with the Portland-based Wild Salmon Center, found that Indigenous Fishing practices (such as reef and dip nets) had a significantly less damaging effect on the local ecosystems compared to areas that used commercial fishing techniques. There is still hope for First Nations’ salmon runs; as long as the changes in the balance of power, all these people reclaim their land and cultural practices.

Source

- https://www.nps.gov/olym/learn/nature/the-salmon-life-cycle.htm

- http://www2.laiwanette.net/fountain/return-to-the-water-first-nations-relations-with-salmon/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coast_Salish_people_and_salmon

- https://nwifc.org/about-us/fisheries-management/questions-and-answers-on-tribal-salmon-fisheries/

- https://phys.org/news/2020-12-indigenous-revitalize-pacific-salmon-fisheries.html