For this edition of my Civic Issues blog, I figured I’d venture out a bit from the typical “Save the World” environmental issues discussion. Some of you might recognize the title of this post as the “slogan” from the 1996 movie “Twister.” Yup, this week we will be looking at climate change and the effects it may or may not have on Tornado frequency and strength. I find this to be a fascinating topic (partially because I’d wanted to be a tornado chaser since I was 5 until I changed to engineering) so to make this post more relatable, I thought we’d take a particularly close look at America’s Tornado Alley.

For this edition of my Civic Issues blog, I figured I’d venture out a bit from the typical “Save the World” environmental issues discussion. Some of you might recognize the title of this post as the “slogan” from the 1996 movie “Twister.” Yup, this week we will be looking at climate change and the effects it may or may not have on Tornado frequency and strength. I find this to be a fascinating topic (partially because I’d wanted to be a tornado chaser since I was 5 until I changed to engineering) so to make this post more relatable, I thought we’d take a particularly close look at America’s Tornado Alley.

There has been debate for some years now between climatologists, meteorologists, and geologists (so many “-ologists,” I know, bear with me) over whether climate change is creating an environment filled with greater, more powerful, and ergo more disastrous storms. While the debate mostly concerns all natural disasters, America sees more tornadoes than any other country in the world, and we are therefore more concerned with the connection between our changing world and these deadly storms.

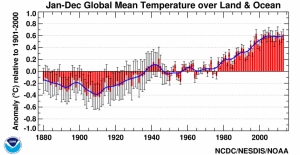

When looking at the relationship between climate change and tornado activity, one must first look at exactly what these “changes” in climate are. One of these main changes (and one that is also heavily debated) is global warming. With temperatures on the rise, the conditions for a tornado become more and more likely. More specifically, for us to understand how this relationship occurs, we must understand how tornadoes form. Tornadoes are truly the result of only “perfect” conditions, including the presence of warm, moist air to create convection in the lower level of the atmosphere, which in turn creates unstable air that then generates the supercell thunderstorms required for tornado formation. Based on this information, it is easy to see why there is a correlation between what can be considered global warming and the number of tornadoes seen. In recent years, America has seen a significant increase in average yearly temperature, which could therefore be associated with the increase in tornado activity that has also been seen in recent years.

When looking at the relationship between climate change and tornado activity, one must first look at exactly what these “changes” in climate are. One of these main changes (and one that is also heavily debated) is global warming. With temperatures on the rise, the conditions for a tornado become more and more likely. More specifically, for us to understand how this relationship occurs, we must understand how tornadoes form. Tornadoes are truly the result of only “perfect” conditions, including the presence of warm, moist air to create convection in the lower level of the atmosphere, which in turn creates unstable air that then generates the supercell thunderstorms required for tornado formation. Based on this information, it is easy to see why there is a correlation between what can be considered global warming and the number of tornadoes seen. In recent years, America has seen a significant increase in average yearly temperature, which could therefore be associated with the increase in tornado activity that has also been seen in recent years.

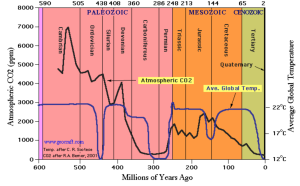

While this correlation is seen by most climatologist to be definitive proof that climate change impacts tornado activity, others are skeptical that the correlation between these two trends is simply a coincidence. In fact, many argue (and truthfully) that global warming is simply an over-exaggeration designed to scare us into treating our planet with respect. One of these arguments includes the basis that compared to others time periods in earth’s development, our climate can be considered relatively cool. On the other hand, while this is obviously true- based on research done by climatologists- we must also consider the temperature changes relevant to our era. In other words, while this time period of the earth’s history can be considered one of the coolest compared to past eras, within this period, our earth’s temperature is rising indefinitely.

While this correlation is seen by most climatologist to be definitive proof that climate change impacts tornado activity, others are skeptical that the correlation between these two trends is simply a coincidence. In fact, many argue (and truthfully) that global warming is simply an over-exaggeration designed to scare us into treating our planet with respect. One of these arguments includes the basis that compared to others time periods in earth’s development, our climate can be considered relatively cool. On the other hand, while this is obviously true- based on research done by climatologists- we must also consider the temperature changes relevant to our era. In other words, while this time period of the earth’s history can be considered one of the coolest compared to past eras, within this period, our earth’s temperature is rising indefinitely.

In addition to the frequency of tornadoes seen, we must also consider the strength of tornadoes seen. For those of you that are not familiar with how tornado strength is measured, the process uses something called the Enhanced Fujita Scale. This scale ranks tornado severity from EF-0 to EF-5 (EF-0 being fairly weak and EF-5 being catastrophic) based on the damage caused from certain windspeed. This scale is essentially just a slight change on the basic Fujita Scale, which has been used for years to rank tornado severity.

Based on this scale, meteorologists have been able to record the severity of tornadoes for years. Looking back through records of tornado development over the past century, we can find the exact number of EF-5 tornadoes that have occurred each year from 1950 to 2013.

Chart based on data found from: http://www.spc.noaa.gov/faq/tornado/f5torns.html

If we look at this chart, it seems as though the number of EF-5 strength tornadoes is simply fluctuating from decade to decade. Based on this, one could conclude that tornado strength may not be increasing at all, let alone being caused by climate change. However, while this small subset of data that I analyzed may not point toward climate change, we must also consider that fluctuations in weather patterns are perfectly normal.

However, as we look deeper into storm strength and climate change, we can find one year in particular that fits this trend: 2011. Many of you probably remember the devastating events of May 22, 2011, when an EF-5 tornado struck Joplin, Missouri and its surrounding areas. What many don’t realize, however, is that an unusually active April preceded this major event. In other words, the midwest essentially got bombarded for a month and a half before the Joplin Tornado struck. This is a documentary regarding the events in Joplin and before (I’m not going to lie, its hard to watch, but the science behind it is interesting):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V_oyBGrxfpg

While these events were truly catastrophic, they speak to something bigger. 2011 saw the most tornado activity since 1947. This may seem like just a weather fluke, but there is a certain correlation between the increased tornado frequency and the average temperature. According to reports given by NASA, 2011 was the ninth-warmest year on record since the year 1880. 2011 was roughly 1 degree Fahrenheit warmer than the baseline average for the 20th century.

While this may not seem like a significant change in temperature, when one looks at the large spike in tornado events that occurred that season, it is clear that this is enough of a change to be concerned.

Overall, the correlation between tornado activity and climate change may seem very controversial for the time being. However, the relationship between the two can be considered both inevitable and potentially catastrophic. While tornadoes are just one subset of the larger category of natural disasters, we can see more or less the same trends occurring with other major storms as well (hurricanes, blizzards, etc.). In fact, for those on the eastern seaboard, and even as far inland as State College , we can recall a relevant example in Hurricane Sandy. While it was not a tornado, there was still a definite debate over the connection between this super storm and the climate change that had preceded it. This storm, like the Joplin Tornado storm, was also a record-breaker. Superstorm Sandy now holds the record for lowest internal barometric pressure for an atlantic storm that passed north of Cape Hatteras. Again, while this may not seem significant now, each record-breaking storm has a potential connection to the climate change that is occurring on our planet, and therefore must be examined as such. In conclusion, as apocalyptic as it sounds, storms like these could potentially become more common as our climate continues to change, and if the conditions are right, we might find ourselves thrown Into the Storm.

For More Interesting Information Regarding Tornado Chasing (Fun Fact-I actually have this NOVA Documentary on that obsolete thing called VHS):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=418U37z_mZA

Interesting Links (and Bibliography):

*Thank You to NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) for being an amazing source for information that was then available for analysis.*

Also, This NOAA Website is just awesome: http://www.spc.noaa.gov/exper/envbrowser

http://www.nasa.gov/topics/earth/features/2011-temps.html

http://www.spc.noaa.gov/faq/tornado/f5torns.html

3 responses to “The Dark Side of Nature”