Welcome back to all of my readers! I am super happy that you are here again.

From the origins of decorative characters to the rise in religious-based writing during the Early Medieval period, calligraphy has developed through the context of its writers’ environments. This remains the same in the case of the Irish-Christians in the British Isles. The discussion of the Christian monasteries in the previous blog post (The Early Role of Religions) can be investigated further by considering the role of Ireland in the evolution of embellished longhand.

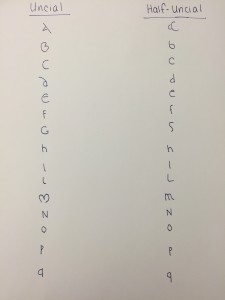

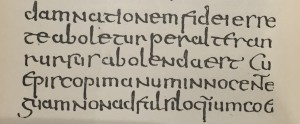

From the middle of the first millennium, Christian monasteries were established across the isolated hills of Ireland; this meant that the practice of bookmaking, which arguably saved much of the remnants of Roman influence, was largely based in this section of the world. The general insular script (related to the uncial and half-uncial scripts) discussed last time was the major ‘font’ base in play. For religious-based texts like the Bible, the half-uncial became the preferred script following the 8th century. These scripts were applied to Christian texts (particularly in Ireland and beyond in the British Isles) with the addition of another layer of artistry. This additional piece to be included in calligraphic writing was the practice of illumination.

Fig 1. The Book of Mulling, 2nd half of the 8th century

(TCD, MS 60, ff. 81v-82) © The Library of Trinity College Dublin.

The illumination that decorated the insular calligraphy further was most often done on parchment – a choice that historians today can be thankful for because it lasts much longer than the alternative of papyrus. A third medium, vellum, was used only if the occasion was significant enough; ceremonial manuscripts were given preference over ones for daily use. As far as scripts go, both the insular majuscule and minuscule (uncial and half-uncial) scripts were used in Ireland and Britain (where Irish missionaries spread their bookmaking processes to). Illumination of a manuscript occurred after the calligraphy was written and dried; it involved leaving a proper blank space on areas of a folio (a folded leaf of the medium). First, metalpoint techniques were applied to the folio to map out the planned design. Clay and sap would next be rubbed on the medium to create something for gold leaf to stick to. Gold leaf was then painted on, followed by the addition of a number of colored paints made from a variety of materials. Check out the top left corners in the photo below to see an example of this!

:focal(664x402:665x403)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c3/32/c332f2e8-eee8-48f8-8f41-96a35dff2ef0/the_book_of_lismore_at_university_college_cork.jpg)

Fig 2. Smithsonian Magazine. The Book of Lismore.

The most famous illuminated manuscript to come out of Ireland by far was the Book of Kells. Still in existence today, the Book of Kells is now on view in the Old Library of Trinity College in Dublin, Ireland.

Fig 3. Trinity College Dublin Digital Collections. Book of Kells Folio 187v: Mark.

The Book of Kells is a Latin-based Celtic version of the Christian New Testament (four gospels in the Bible describing events after the birth of Christ). Produced at the start of the 9th century, it features some of the most well developed aspects of Irish calligraphy from the time. The insular majuscule script fills its many folios, with complicated early versions of the Celtic knot introducing each gospel. It is estimated that multiple scribes were responsible for the copying of the text (as noted by slight differences in writing style and pressure). The Book of Kells is so intricate in motifs surrounding the written word that some folios only have short phrases written on them with the amount of room that the embellishments take up. The manuscript’s style is particular; it demonstrates one of the finest examples of the insular first initial in recorded history. The first letter of the page, or the initial, is consistently the fanciest on any given folio. The image below is of the famous Chi Rho page, which according to BBC Culture uses Ancient Greek to denote the first two letters of ‘Christ’ (click here to learn more). Motifs surround it, encouraging the viewer to appreciate the broader and more beautiful meaning of the written word.

Fig 4. BBC Culture. The Book of Kells: Chi Rho.

It should be noted that Ireland was not the only country experiencing a national development of the calligraphic hand. Italy established a national hand of its own called the Beneventan script. Out of France came the Merovingian minuscule. In the Holy Roman Empire, the influence of Irish monks led to the creation and use of the Carolingian minuscule. Spain saw the advent of its Visigothic script. National styles were created under the circumstances facing a given region. As previously discussed, Ireland’s monasteries were pushed in the direction of bookmaking after the Christian Church took responsibility for it after the fall of Rome. The intense and elaborate decorations on top of the insular script were in observance of the power of religion and religious institutions.

Once again, thank you for exploring embellished writing with me once more. I hope you look forward to next week’s blog post – it will be centered on the internationally recognized gothic style developed in the centuries ahead. See you next time!