We have returned for Week 8 of Calligraphy Corner! It is so good to have you back…

Calligraphy has taken on many different changes over its long history. On the previous blog, we covered some shifts that occurred primarily from the mid-19th century to the beginning of the 20th. Today, we will be focusing solely on the 20th century and the developments that occurred before the world transitioned into World War 2. Because so much was happening in this time frame, I would like to introduce a few separate developments before offering a final opinion.

Many new artists began to get involved in the western calligraphic landscape with the turn of the century. Schools across Europe began to offer courses in decorative handwriting in the image of Edward Johnston. The artists who learned and taught at these schools include the likes of William Graily Hewitt (Graily Hewitt) and Rudolf von Larisch.

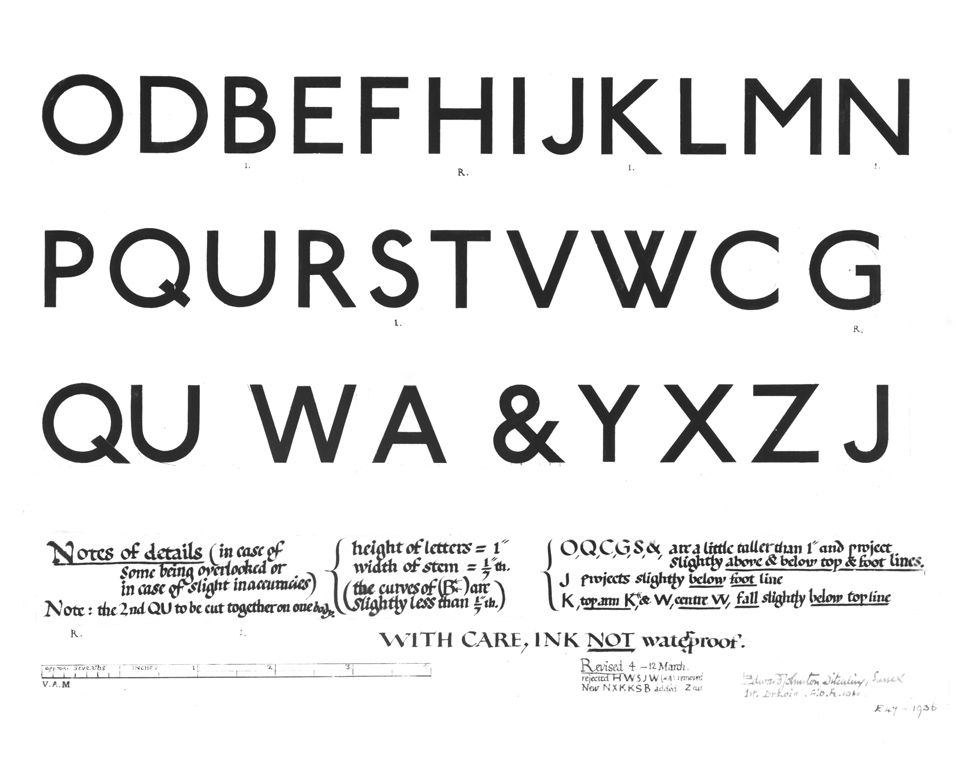

William Graily Hewitt was a figure whose contributions to the field were so great that they compare with Johnston’s large impact. He learned under Johnston at the Central School and later taught his own classes based on Johnston’s previous instruction. Graily Hewitt’s professional life even consisted of collaborations with Johnston in the 1920s and 1930s. His main focus in the arts concerned the practice of illumination. He used gold leaf in gilding, a process that ultimately results in the application of illuminated gold to calligraphic letters. His role as Johnston’s successor in the comeback of calligraphy was made evident in the appointment he was given to create the announcement for Prince Phillip that his new title would be styled as the Duke of Edinburgh upon his wedding to the future Queen Elizabeth. Until Hewitt’s death in 1952, he continued practicing calligraphy on commission and wrote numerous books on making typefaces with pen and ink.

![LOT:31 | Calligraphy & Private Press.- Hewitt (Graily) Truth, calligraphic manuscript, [c. 1920]; and a small quantity of letters and postcards from various Private Presses and artists (c. 35 pieces).](https://smhttp-ssl-53905.nexcesscdn.net/catalogue_images/auction//large/14085-104_1.jpg)

Fig 1. Forum Auctions. Calligraphy & Private Press – Hewitt.

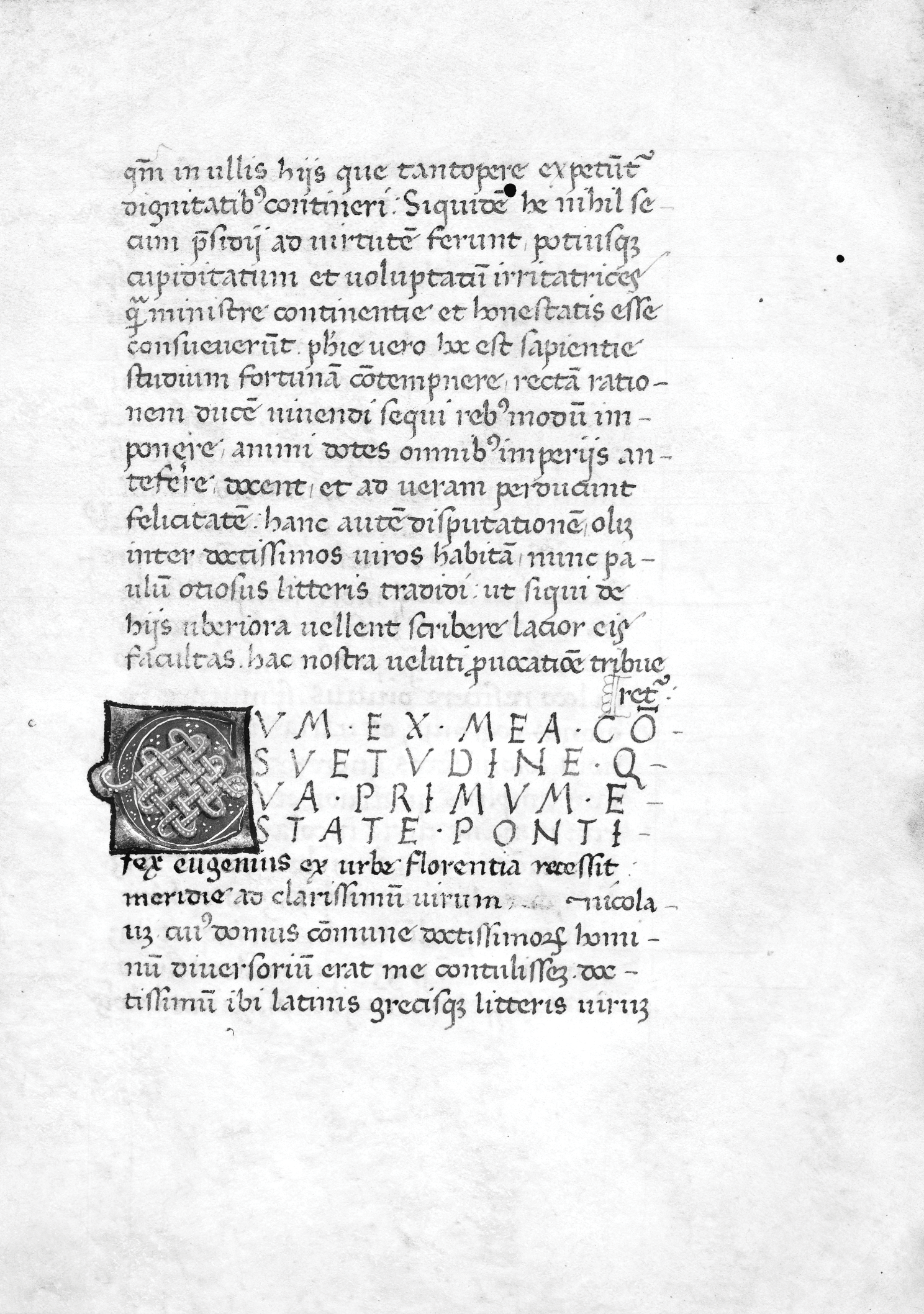

In the years between the first and second World Wars, calligraphy experienced extreme influence from English and German cultures. Schools in London like the Central School, as well as the Vienna School of Art in Germany, had instructors who wrote and published handwriting books to practice with. In Germany and Austria specifically, the Gothic hand still had a high relevance on official papers and the arts. The revival of calligraphy in these countries in particular had some interesting twists and turns. Rudolf von Larisch, an archivist from Austria who worked in Vienna, applied the concepts of past materials in discovering how tools influence writing and vice versa. He made multiple typefaces in his exploration of his so called “language of materials.” His highly technical approach influenced the modernization of calligraphy in Germany for years to come.

Fig 2. Luc Devroye. Rudolf von Larisch.

The growing interest in traditional handwriting techniques stemming from the Arts and Crafts movement in England (previous discussed last week!) eventually led people who shared this passion to come together and form a group called the Society of Scribes and Illuminators. This society was created in 1921 for the purpose of understanding calligraphy and illumination as both a historical and a contemporary type of art. Several of those who were formerly taught under the leadership of Edward Johnston wanted to celebrate technical prowess and dedication to the craft. Graily Hewitt, one of these former students, was one of the Society of Scribes and Illustrator’s original founders! This society has prolonged the influence of calligraphy by publishing textbooks, establishing a membership program, setting up a library for use of its fellows, and spreading the art’s influence in various workshops and exhibits. It remains in existence today, largely under the same purpose as its founders intended.

Fig 3. The Society of Scribes and Illuminators. George Thompson Gallery.

Overall, we can definitely see how a small growing interest in this topic led to a wider degree of knowledge and attraction to the art of calligraphy. Different societies and organizations had formed in this time in celebration of the written word. Beyond professional groups, people from around the world were given access to a variety of handbooks and instructional guides that allowed them a means of entry into a highly professional and technical world. Different typefaces were even used as part of promotions and important announcements! As a whole, the modern calligraphy movement began to grow a substantial base during this time. This is heavily indicated by the fact that some of Europe’s most prestigious institutions had teachers willing to show interested pupils how to write in different hands and how to maintain specific skills sets for a variety of writing tools. In World War 2 and its aftermath, the landscape changed dramatically in a way that typefaces and fonts were used for marketing techniques to persuade consumers to join a cause or buy a product. We will cover more about calligraphy’s impact on marketing on the next blog!

See you next time!