Archive of ‘Uncategorized’ category

When you hear the term ‘school safety’ what do you think of?

Is it the severe weather drills you practiced a couple of times over the course school year ? Or an elementary teacher preaching safety after giving the stereotypical ‘don’t run with scissors’ talk?

For many people, myself included, the issue of school safety is far more serious.

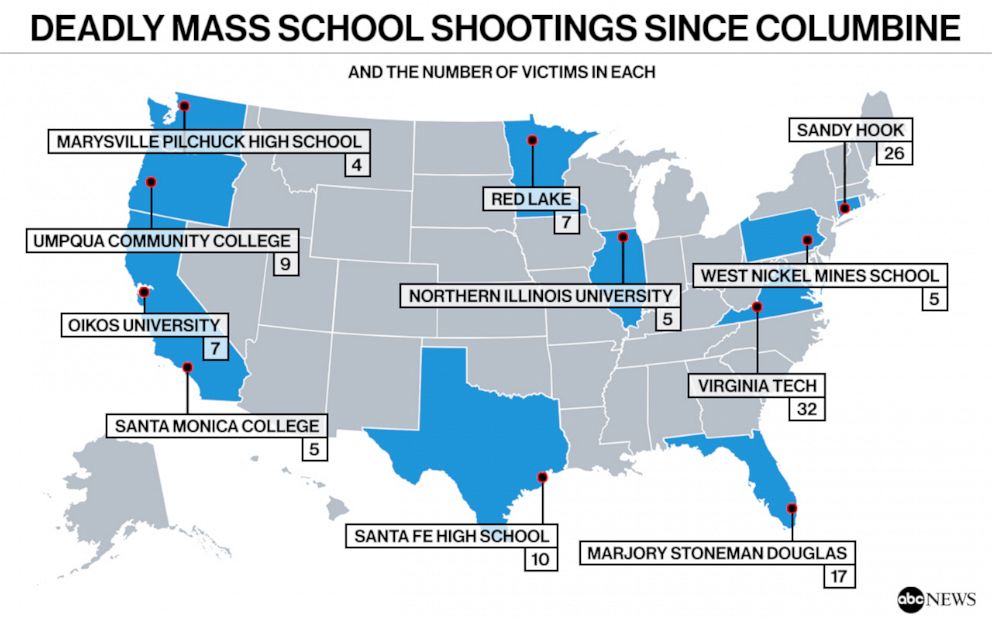

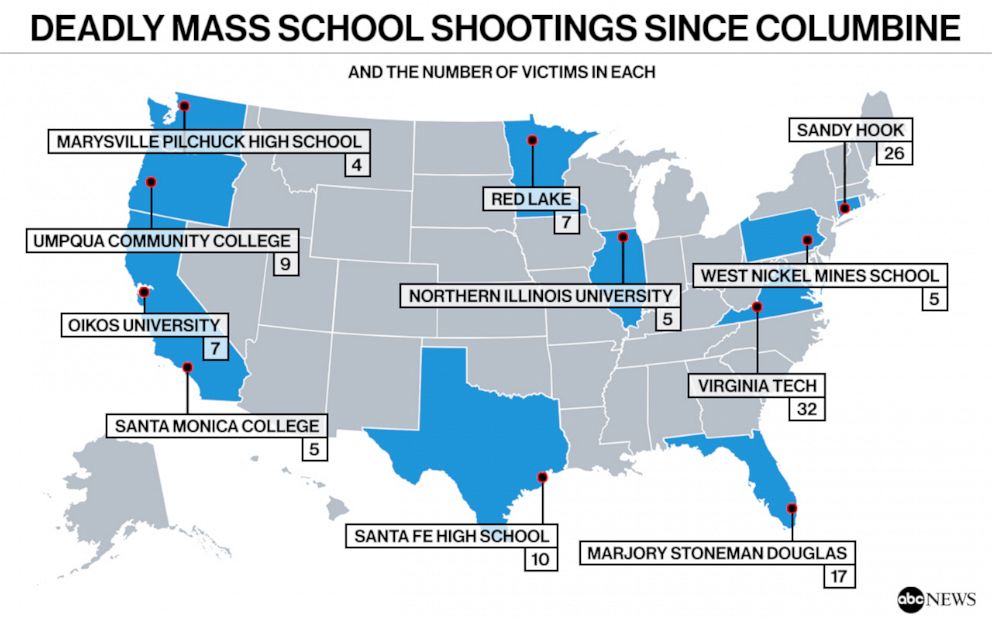

School shootings and other related mass acts of violence have plagued the American education system since before its founding. They have only increased in severity and frequency with every passing year. Since 1970, the United States witnessed an estimated 1,316 school shootings. In 2018 along, the nation experienced about 340 shootings, nearly one for every day of the year.

frequency with every passing year. Since 1970, the United States witnessed an estimated 1,316 school shootings. In 2018 along, the nation experienced about 340 shootings, nearly one for every day of the year.

These shootings and other tragedies are often termed as a uniquely American phenomenon, because, while other nations occasionally suffer from these types of events, the United States does so at a disproportionately higher rate. In fact, in a study conducted by CNN using data compiled from the other industrialized nations, it was found that the United States had 57 times as many school shootings as the other nations combined. In terms of acts of violence in which someone sadly lost their life, it was reported that in the 2000s there were 57 incidents of mass violence in 36 countries, with over half (28) occurring in the United States.

Being such a prevalent and ongoing issue, there have been a number of solutions proposed to eliminate, or at least lessen, the amount of these attacks.

I’m going to briefly detail some of the most popular or controversial ones.

Some people believe that to combat gun violence in schools, teachers should be armed. Supporters of this solution believe that having a select number of specially trained teachers carrying firearms, they would be able to save lives in the event of an active shooter; they also believe that this would deter people from planning or attempting to carry out an attack. People who disagree with this approach believe this would cause more harm than good, leading to accidents, injuries, and fear amongst the students.

Other people advocate for less intense (and more professional) interventions, such as the installation of metal detectors and other preventative equipment and the employment of school resource officers and other trained professionals. Metal detectors as part of a schools safety protocol, for example, would catch a potential attack before any damage is done. SROs, as school resource officers are called, are trained to respond to an active shooter situation and how to de-escalate a shooter. While there are positives to this approach and it is helpful, some would argue that it simply would not be enough.

Going along with preventative measures, another potential solution that many people support is giving students the help and resources they need before they even think of committing an attack. This would include revamping mental health programs and anti-bullying initiatives along with other programs. Personally, I favor this approach the most.

What solution do you think would best solve or work to solve this issue?

At some point in your academic career, you have most likely taken an elective course, whether it be for fun to explore an area of interest or simply to fulfill a graduation requirement.

Elective courses, and discussions about their merit and need, have been a hot topic in talks regarding education, school curriculums, and (yes, you guessed it) school funding.

Elective courses, and discussions about their merit and need, have been a hot topic in talks regarding education, school curriculums, and (yes, you guessed it) school funding.

Students either love electives or hate them with a burning passion.

Let’s get into some views from both sides of the argument, beginning with the benefits of taking an elective course.

Elective courses, especially in middle and high school, are extremely helpful in broadening a student’s academic horizon far beyond what is taught and reinforced in core classes and the standard education. These classes, which can span from ‘The Basics of Photoshop’ to ‘Personal Finance and Accounting 101,’ give students the opportunity to pick and choose what material they would like to learn, allowing them to get a more in-depth understanding of a subject they may want to pursue as a career or explore new subjects and interests altogether. These courses also reinforce skills developed in other classes and teach students other valuable life skills and abilities. In this way, elective courses are very similar to the “specials” many elementary age students rotate through during their typical school week. For young students, these courses enrich understanding through hands-on activities and interactions, including (but not limited to) classes in visual art, physical education, library skills, computer science, and music and the performing arts. These specials teach and foster valuable skills, such as personal health, creativity, and imagination, that are not typically emphasized in the traditional classroom setting. Electives in middle and high school are virtually doing the same thing, but at a higher learning level.

other valuable life skills and abilities. In this way, elective courses are very similar to the “specials” many elementary age students rotate through during their typical school week. For young students, these courses enrich understanding through hands-on activities and interactions, including (but not limited to) classes in visual art, physical education, library skills, computer science, and music and the performing arts. These specials teach and foster valuable skills, such as personal health, creativity, and imagination, that are not typically emphasized in the traditional classroom setting. Electives in middle and high school are virtually doing the same thing, but at a higher learning level.

Subsequently, by allowing students to make choices in education by choosing which electives to take, students become more engaged and motivated in school, as they are learning about a subject or understanding how to perform a skill that interests them. According to Robert Marzano, an education researcher, the ability to make choices “has been linked to increases in student effort, task performance, and subsequent learning.”

Despite being called elective courses, students are not always given the choice of whether or not they would like to enroll in a course. The best example of this situation is general degree requirements for students pursuing a degree in a college or university.

Many college students, especially those in rigorous or work-heavy programs, find taking electives pointless and a waste of time. For the most part, students in college already know what they plan to pursue, so why make them take classes that do not relate to their major at all? One of the main arguments against this point is that taking a large variety of electives from a plethora of subjects and disciplines makes students more informed and a better, well-rounded person all together. While this may be true, it is hard to ignore how, as one writer put it, general electives “detracts from valuable study, work or leisure time that’s already thinly parsed.”

Where am I in this argument?

I agree with both sides. Electives are very helpful not only in educating but engaging students throughout their early schooling carrer, but when they progress to means of higher education, I find electives more troublesome than helpful.

I have always dreaded taking assessments.

During high school, in the few minutes leading up to the start of a big exam, I would sit with my clammy palms tightly gripping a pencil, one leg quickly bouncing underneath the desk, and my eyes frantically watching the hands on the clock, waiting for the bell to ring so the test could begin and the internal suffering I have felt for days could finally cease. Even now, taking classes from the comfort of my home, I still feel that terrible panic rising up my throat and controlling all of my senses before I click the blue “Begin Quiz” button on Canvas.

Like many others, one of the main reasons for my extreme test-taking anxiety is the time limit set on certain assessments.

When an assessment has a set time limit, it adds additional stress to an already stressful and anxiety inducing situation, especially in high stake testing scenarios, such as when a student’s score on an exam that counts for a large portion of their final grade or determines whether or not they will go to a specific school or get a certain license. One recent study found that the average high school student in 2000 had the same anxiety levels as the average psychiatric patient in the 1950s.

Another study from the last few years discovered that the average student had 15 percent more cortisol in their systems before high stake testing than on days with no high-stakes testing. These students typically performed worse on the assessment than they did on in-class exercises and other tests. Cortisol, most commonly known to be affiliated with the  body’s “fight or flight” instinct, is the body’s main stress hormone. This study, published in the National Bureau of Economic Research, also found the opposite, claiming the students whose cortisol levels dropped performed even worse. According to Jennifer Heissel, one of the researchers, “the decrease in cortisol is more a sign that your body is facing an overwhelming task and your body does not want to engage with the test.”

body’s “fight or flight” instinct, is the body’s main stress hormone. This study, published in the National Bureau of Economic Research, also found the opposite, claiming the students whose cortisol levels dropped performed even worse. According to Jennifer Heissel, one of the researchers, “the decrease in cortisol is more a sign that your body is facing an overwhelming task and your body does not want to engage with the test.”

Besides inciting stress, another large issue with the widespread use of timed assessments is that they evaluate students on speed and memorization rather than understanding. For many students, they understand the testing material very well, but need time to read and reread the prompt to fully understand what a multiple choice question, math problem, or essay is asking. These students are then discouraged and penalized with a poor grade when they run out of time and are unable to complete the assessment.

In order to lessen student stress and make exams fair for all types of learners, I believe time restrictions should be taken off assessments.

Online learning.

Something we have all grown very familiar with over the last year and something I, along with many others, have grown to disdain.

Even though my hatred for online learning increases exponentially with every zoom meeting and notification about a posted asynchronous class lecture, I believe right now online learning is the safest, and therefore best, option. With the severity and deadly nature of the pandemic, it is in everyone’s best interest to social distance and stay out of large crowds until enough of the population receives the vaccine and we reach herd immunity. We cannot do this in crowded classrooms, cafeterias, libraries, and lecture halls.

pandemic, it is in everyone’s best interest to social distance and stay out of large crowds until enough of the population receives the vaccine and we reach herd immunity. We cannot do this in crowded classrooms, cafeterias, libraries, and lecture halls.

While I agree this positive of preventing the spread of Covid-19 and saving lives dwarfs the negatives, making them seem insignificant in comparison, there are still many problems with online learning.

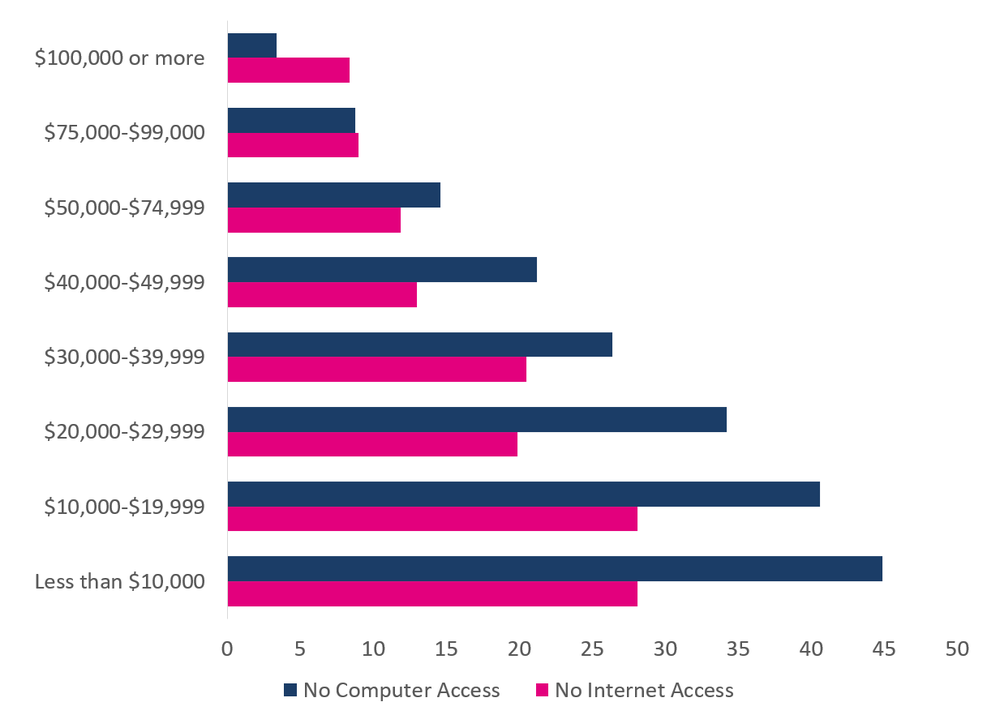

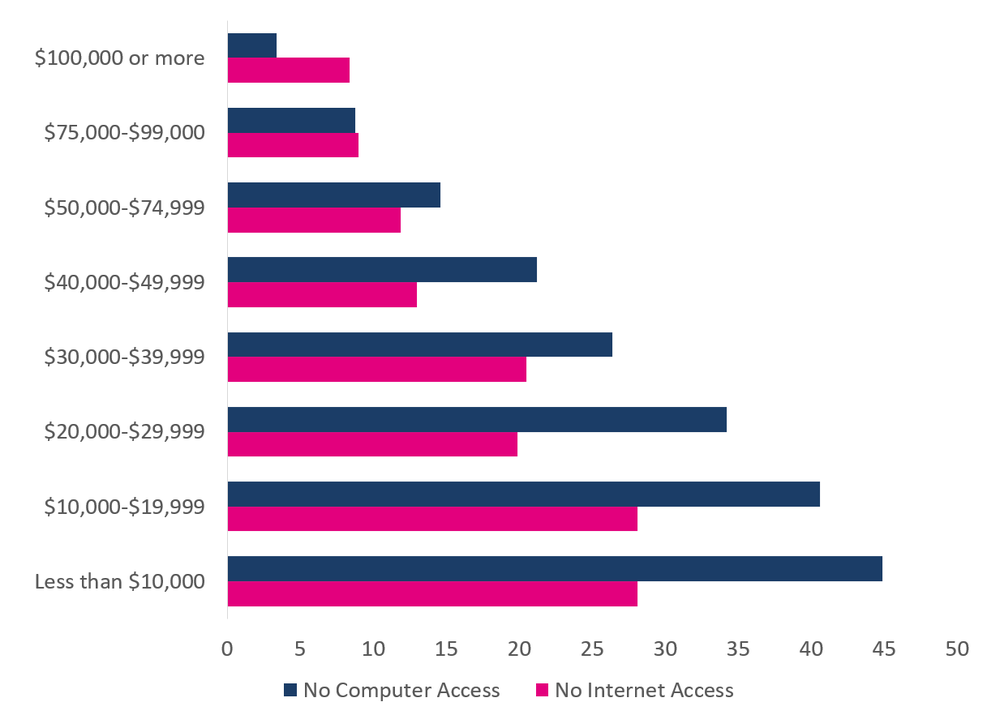

One of the most important issues with online learning deals with technology accessibility and equity. In order for students to be successful while taking classes and learning online, which  is a struggle to adjust to in itself, students must first be able to have reliable and consistent access to the internet. Among a great deal of people, including a disproportionate amount living in rural and low socioeconomic communities, access to the internet is simply not a possibility. Currently in California, even after months upon months of online learning, an estimated 700,000 students still need devices like laptops or Chromebooks to do their school work and attend class. An estimated 300,000 lack internet connectivity to ensure full participation in distance learning.

is a struggle to adjust to in itself, students must first be able to have reliable and consistent access to the internet. Among a great deal of people, including a disproportionate amount living in rural and low socioeconomic communities, access to the internet is simply not a possibility. Currently in California, even after months upon months of online learning, an estimated 700,000 students still need devices like laptops or Chromebooks to do their school work and attend class. An estimated 300,000 lack internet connectivity to ensure full participation in distance learning.

Another major problem with online learning is how it impacts students socially. While social isolation has become a common trend due to the ever-present quarantine, it is especially detrimental when students of all grades and ages are trying to learn. According to Sander Tamm from e-student.org, “The e-learning methods currently practiced in education tend to make participating students undergo contemplation, remoteness and a lack of interaction.” In addition to preventing them from acquiring team building and similar social skills developed through in-person learning, learning in an online environment hinders students from grasping their studied material due to a lack of personal connections with their educators. Many students need to do that in person contact during office hours to go over work and fully understand everything. Due to the online nature of their education, however, many students, plagued with zoom fatigue and a great deal of stress, avoid reaching out for extra help.

Those are just two of the major issues with online learning.

All things considered, online learning is not by any means perfect, but it is the best we can work with at this moment. I believe everyone needs to wear their masks and keep social distancing so we can bid adieu to the black boxes of zoom and go back to traditional in-person learning as quickly as possible.

From children in kindergarten classrooms to young adults working towards a Masters or Doctorate degree, the letter grading system is a familiar faucet of academics for nearly all people. Sparking discourse and debate since its creation, letter grading is one of many controversial aspects of the American School System.

Along with many others, I have a lot of problems with letter grades and the role they currently play in education.

The first grading scale was created in 1785 by Ezra Stiles, the then president of Yale University. Rather than using A’s, B’s, C’s, D’s, and F’s to denote one’s academic performance, Stiles’ grading system was based on a four point scale, each with an accompanying latin description. These phrases, which were Optimi, Second Optimi, Inferiores, and Perjores respectively, roughly translate to best, second best, less good, and worse. A few decades later, these descriptions were replaced with a numeral system with one representing the best, or highest score, and four representing the worst, or lowest score. While other universities during this time utilized a variety of different grading scales to categorize their students, many people believe Stiles’ system to be the first attempt at creating standardized grading practices.

Inferiores, and Perjores respectively, roughly translate to best, second best, less good, and worse. A few decades later, these descriptions were replaced with a numeral system with one representing the best, or highest score, and four representing the worst, or lowest score. While other universities during this time utilized a variety of different grading scales to categorize their students, many people believe Stiles’ system to be the first attempt at creating standardized grading practices.

The advent of the letter grading system we see most commonly used today was due in part to the implementation of compulsory education laws from the late 19th century to the early 20th century. With such a great volume of children and teenagers now required to attend classes, school systems needed an efficient and standardized system for evaluating performance and progress; hence the birth of letter grading.

Contrary to popular belief, the letter grading system is a relatively new component of the American School System. Despite being created early on, letter grading was not in widespread use until around the 1940s. In fact, studies show that even in 1971, only 67% of American primary and secondary schools utilized this system. Now, nearly all education institutions, from small rural elementary schools to large public universities, distribute letter grades.

One of the main reasons why a large portion of the population disagrees with the use of letter grades involves student motivation. While most can agree that letter grades motivate students of all ages to do well in school, it is not necessarily for the purpose of expanding one’s knowledge or becoming more informed in a particular area of study. In a society that heavily focuses on getting “good” grades, constantly perpetuating the importance of having all A’s and a 4.0 GPA, many students are extrinsically motivated to perform well in school, meaning they are solely motivated by an outside form of compensation or validation (i.e. grades). Rather than being intrinsically motivated, or motivated by an inner drive and desire, students often only focus on required readings and graded assignments in order to reach the standard set by letter grades. This type of motivation inadvertently limits students’ knowledge as they will not be inclined to do further research on and explore a component of the course they find to be especially interesting. Overall, the letter grading system muddles the true purpose of acquiring an education by making an A or B be the end goal of a class or year rather than the information one absorbs and learns along the way.

meaning they are solely motivated by an outside form of compensation or validation (i.e. grades). Rather than being intrinsically motivated, or motivated by an inner drive and desire, students often only focus on required readings and graded assignments in order to reach the standard set by letter grades. This type of motivation inadvertently limits students’ knowledge as they will not be inclined to do further research on and explore a component of the course they find to be especially interesting. Overall, the letter grading system muddles the true purpose of acquiring an education by making an A or B be the end goal of a class or year rather than the information one absorbs and learns along the way.

Another prominent criticism of letter grading is how it negatively impacts students’ mental health by increasing stress and anxiety levels. According to Denise Clark Pope, a lecturer and author, pressure to achieve top scores has created stress levels among students – beginning as early as elementary school – that are so high that some educators regard it as a health epidemic. By having so much stress associated with the letter grading system, as a letter grade holds so much power in determining one’s future, image, and self-perception, it further distorts the definition of education. As opposed to being an enlightening experience, learning is made out to feel stressful and burdensome.

Because letter grading is doing more harm that good for students’ education and feelings towards acquiring knowledge, the American School System should adapt new methods of evaluating students and their academic abilities.

frequency with every passing year. Since 1970, the United States witnessed an estimated 1,316 school shootings. In 2018 along, the nation experienced about 340 shootings, nearly one for every day of the year.

frequency with every passing year. Since 1970, the United States witnessed an estimated 1,316 school shootings. In 2018 along, the nation experienced about 340 shootings, nearly one for every day of the year.

Elective courses, and discussions about their merit and need, have been a hot topic in talks regarding education, school curriculums, and (yes, you guessed it) school funding.

Elective courses, and discussions about their merit and need, have been a hot topic in talks regarding education, school curriculums, and (yes, you guessed it) school funding.  other valuable life skills and abilities. In this way, elective courses are very similar to the “specials” many elementary age students rotate through during their typical school week. For young students, these courses enrich understanding through hands-on activities and interactions, including (but not limited to) classes in visual art, physical education, library skills, computer science, and music and the performing arts. These specials teach and foster valuable skills, such as personal health, creativity, and imagination, that are not typically emphasized in the traditional classroom setting. Electives in middle and high school are virtually doing the same thing, but at a higher learning level.

other valuable life skills and abilities. In this way, elective courses are very similar to the “specials” many elementary age students rotate through during their typical school week. For young students, these courses enrich understanding through hands-on activities and interactions, including (but not limited to) classes in visual art, physical education, library skills, computer science, and music and the performing arts. These specials teach and foster valuable skills, such as personal health, creativity, and imagination, that are not typically emphasized in the traditional classroom setting. Electives in middle and high school are virtually doing the same thing, but at a higher learning level.

body’s “fight or flight” instinct, is the body’s main stress hormone. This study, published in the National Bureau of Economic Research, also found the opposite, claiming the students whose cortisol levels dropped performed even worse.

body’s “fight or flight” instinct, is the body’s main stress hormone. This study, published in the National Bureau of Economic Research, also found the opposite, claiming the students whose cortisol levels dropped performed even worse.  pandemic, it is in everyone’s best interest to social distance and

pandemic, it is in everyone’s best interest to social distance and  is a struggle to adjust to in itself, students must first be able to have reliable and consistent access to the internet. Among a great deal of people, including a disproportionate amount living in rural and low socioeconomic communities, access to the internet is simply not a possibility. Currently in California, even after months upon months of online learning,

is a struggle to adjust to in itself, students must first be able to have reliable and consistent access to the internet. Among a great deal of people, including a disproportionate amount living in rural and low socioeconomic communities, access to the internet is simply not a possibility. Currently in California, even after months upon months of online learning,  Inferiores, and Perjores respectively, roughly translate to best, second best, less good, and worse. A few decades later, these descriptions were replaced with a numeral system with one representing the best, or highest score, and four representing the worst, or lowest score. While other universities during this time utilized a variety of different grading scales to categorize their students, many people believe Stiles’ system to be the first attempt at creating standardized grading practices.

Inferiores, and Perjores respectively, roughly translate to best, second best, less good, and worse. A few decades later, these descriptions were replaced with a numeral system with one representing the best, or highest score, and four representing the worst, or lowest score. While other universities during this time utilized a variety of different grading scales to categorize their students, many people believe Stiles’ system to be the first attempt at creating standardized grading practices.  meaning they are solely motivated by an outside form of compensation or validation (i.e. grades). Rather than being intrinsically motivated, or motivated by an inner drive and desire, students often only focus on required readings and graded assignments in order to reach the standard set by letter grades. This type of motivation inadvertently limits students’ knowledge as they will not be inclined to do further research on and explore a component of the course they find to be especially interesting. Overall, the letter grading system muddles the true purpose of acquiring an education by making an A or B be the end goal of a class or year rather than the information one absorbs and learns along the way.

meaning they are solely motivated by an outside form of compensation or validation (i.e. grades). Rather than being intrinsically motivated, or motivated by an inner drive and desire, students often only focus on required readings and graded assignments in order to reach the standard set by letter grades. This type of motivation inadvertently limits students’ knowledge as they will not be inclined to do further research on and explore a component of the course they find to be especially interesting. Overall, the letter grading system muddles the true purpose of acquiring an education by making an A or B be the end goal of a class or year rather than the information one absorbs and learns along the way.