The idea of trickle-down environmentalism is as alluring as it is flawed, mimicking the deficiencies of its economic predecessor. Well-intentioned proponents of the idea suggest if the elite embrace sustainability, their behaviors will set an example that trickles down to the rest of society, leading to widespread environmental action. However, this idea falls short of addressing the complexities intrinsic to the social dilemmas facing society in the fight to save our planet.

The idea of trickle-down environmentalism is as alluring as it is flawed, mimicking the deficiencies of its economic predecessor. Well-intentioned proponents of the idea suggest if the elite embrace sustainability, their behaviors will set an example that trickles down to the rest of society, leading to widespread environmental action. However, this idea falls short of addressing the complexities intrinsic to the social dilemmas facing society in the fight to save our planet.

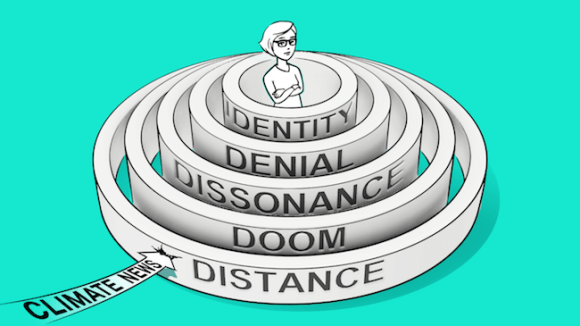

Trickle-down environmentalism fails to consider the inherent inequity in environmental impact. A recent journal article asserts that around 50% of global emissions are caused by the wealthiest 10% of the world’s population, while the poorest half of the world’s citizens–those most impacted by the crisis–contribute only 7% (Starr et al., 2023). Further widening the inequity, the richest are living lifestyles far removed from the consequences of their environmental choices. Who are the “rich?” An annual income of $38,000+ is the entry point to the world’s wealthiest 10%; if one makes more than $109,000, they skyrocket into the world’s top 1%. The disconnect between actions and consequences creates a buffer that downplays the urgency for change among elites, a problem exacerbated by cognitive dissonance. Cognitive dissonance occurs when we attempt to hold incongruent understandings or beliefs simultaneously. This causes psychological stress, and leads us to change, downplay, add, or remove cognitions until they are consistent (Gruman et al., 2016). For the affluent, who contribute significantly to environmental degradation yet experience minimal personal impacts, the dissonance is negligible, and there exists little incentive to change.

The effects of the climate crisis most severely impact those least responsible. Climate change does not affect all equally; it disproportionately targets the poorest and most vulnerable communities, further entrenching systemic inequities. The rich, insulated by their wealth, are often the last to feel the effects, resulting in a delayed and often diluted response. The creation of “loss and damage” funding at the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP27) was predicated upon the widespread belief that those initiating and benefitting from the emissions driving climate change should shoulder some of the responsibility to address the damage caused to communities hit hardest by their actions (Starr et al., 2023). The question is, though, are top-down initiatives enough? The answer, quite simply, is no. Trickle-down environmentalism requires buy-in those at the top likely cannot manufacture, because cognitive transformation is required to activate behavioral change (Shao et al., 2023). Cognitive transformation generally requires an experience that changes our perspectives. Individuals must understand and internalize the importance of these actions, which often requires direct experience with the adverse effects of climate change—something the wealthy are shielded from.

Experiential Learning Theory (ELT), developed by David Kolb, posits that individuals learn and change their behaviors through experiences, especially when experiences challenge their existing beliefs or knowledge, (i.e. when cognitive dissonance exists). Transformational experiences lead to experiential knowledge, which, in this context, could lead to environmental behavior change. But how will the top 10% learn experientially the impact of our toxic contributions?

There exists another pitfall working against our environment. Social Learning Theory, generally associated with positive learning and modeling, may not always produce positive outcomes. This theory emphasizes the role of observational learning, imitation, and modeling in human behavior. According to Social Learning Theory, people learn from observing others, particularly those they consider role models or aspire to be like (Gruman et al., 2016). According to the tenets of this theory, if the poor aspire to be wealthy, they may emulate the rich; in seeking wealth, they may adopt the same harmful environmental behaviors. This aspirational mimicry is a significant risk, as it suggests that the actions of the rich could perpetuate and exacerbate existing environmental problems. As it relates to trickle-down environmentalism, the theory suggests those at the top, typically the wealthiest and most influential in society, are less likely to experience direct, adverse effects of climate change. Thus, they have little experiential learning to catalyze genuine understanding and behavioral change toward environmental conservation. Their decisions and behaviors are less likely to be influenced by the environmental crises that disproportionately affect less affluent communities.

We know environmental crises demand a robust and inclusive approach. We likely cannot rely on the behaviors of the most affluent to lead the way. Instead, we need systemic change that involves all levels of society. We must empower the most vulnerable, promote widespread cognitive transformation, and ensure that environmental action is not a luxury of affluence but a universal commitment. We know what must be done. The question is: how do we do it?

-Laura Gamble

References

Gruman, J. A., Schneider, F. W., Coutts, L. M. (2016). Applied Social Psychology : Understanding and Addressing Social and Practical Problems (3rd ed.). : SAGE Publications. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/pensu/reader.action?docID=5945490&ppg=46

Shao, X., Jiang, Y., Yang, L., & Zhang, L. (2023). Does gender matter? The trickle‐down effect of voluntary green behavior in organizations. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 61(1), 57-78. https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-7941.12348

Starr, J., Nicolson, C., Ash, M., Markowitz, E. M., & Moran, D. (2023). Assessing U.S. consumers’ carbon footprints reveals outsized impact of the top 1. Ecological Economics, 205, 107698. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2022.107698

Warner, L. A., Cantrell, M., & Diaz, J. M. (2022). Social norms for behavior change: A synopsis: WC406/AEC745, 1/2022. EDIS, 2022(1). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-wc406-2022