Author: Hoang (Bolton) Tran

Problem statement [1]

Platinum (Pt) crystal structure are hypothesized to take the form of either a simple cubic (SC), a face-centered cubic (FCC) or a hexagonal closed pack (HCP) structure.

Density functional theory [2] (DFT) calculation is used to first, find the optimal lattice constant for each of the proposed structure. The optimal lattice constant is one that yields the lowest cohesive energy (E) per atom in the unit cell. Then, the lowest cohesive energy among the three structures would indicate which structure is optimal for Pt.

Methodology

Software:

DFT calculation is carried out using CAmbridge Serial Total Energy Package (CASTEP), a plane wave basis set tool that embedded inside BIOVIA Material Studio (MS) software. [3]

Calculation:

1. DFT energy calculation setting:

- Exchange-Correlation Functional: Generalized Gradient approximations – Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (GGA-PBE) [4]

- Self-Consistent Field tolerance: 2E-06 eV

- Pseudo potential: On-the-fly Generated (OTFG) ultrasoft (Vanderbilt-type) [5]. Core radius: 2.4 a.u.. Core orbitals: 1s2 2s2 2p6 3s2 3p6 3d10 4s2 4p6 4d10

Cohesive energy is calculated by subtracting the atomic pseudo energy (-13042.3015 eV) from the estimated 0 K energy. All energy is in per atom basis.

2. Lattice constant optimization

Crystal structures of Pt are generated in MS with editable lattice constant.

The lattice constant for SC and FCC is a which is side length of the cubic unit cell. a is varied and the cohesive energy (E) is calculated. Data of E vs. a is then fitted to the Birch-Murnaghan (BM) equation of state [6]. Then the minimum a from the fitted function is considered as the optimal lattice constant.

The lattice constants for HCP are a and c, the basal side length and height respectively. All lattice constants are defined and optimized in its primitive cell.

3. Convergence

The energy cutoff for plane wave set is varied for a particular set of lattice constant optimization. As energy cutoff is incremented, the minimum cohesive energy is calculated until the difference with respect to result at highest energy cutoff is less than 0.01eV . This optimal energy cutoff is then used throughout all calculations.

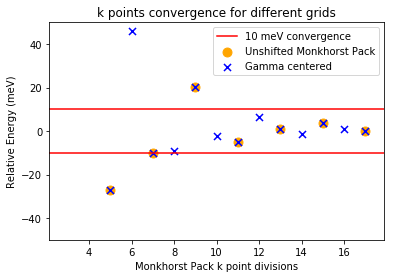

The kpoints, which represent Monkhorst-Pack sampling space [7] for the plane wave, is optimized for each crystal structure. The grid parameters for k space is varied for each set of lattice constant optimization and then optimized similarly to energy cutoff, i.e. until minimum cohesive energy does not change by more than 0.01 eV with respect to highest kpoints result.

Results

1. Energy cutoff optimization:

Simple cubic structure is chosen to be optimized in term of energy cutoff at constant kpoints of 120 (15x15x15 grid). The lattice constant a is varied from 2 to 3.5 Å and cohesive energy is extracted and fitted to BM equation. Similar procedure is then repeated for different values of energy cutoff. Figure 1 illustrate such fitting for two values of energy cutoff. Python’s scipy.optimize module [8] is used to find the minimum energy for each fitted function.

Table 1 below shows that the minimum cohesive energy goes down as energy cutoffs increases. Difference with respect to highest energy cut off (i.e. 450 eV in this case) is used as the criteria of convergence. Therefore, 400 eV point would be considered as converged because it differs from 450 eV point by less than 0.01 eV. But as to ensure good convergence throughout, 450 eV will be used as the optimal energy cutoffs for all following calculations.

Table 1. Minimum total energy at different energy cutoffs – SC

| Energy cutoff (eV) | Minimum total energy (eV/atom) | Difference with respect to highest cutoff (eV) |

|---|---|---|

| 270 | -7.626 | 0.539 |

| 300 | -8.003 | 0.161 |

| 350 | -8.151 | 0.013 |

| 400 | -8.164 | 0 |

| 450 | -8.164 | 0 |

2. Simple cubic

To determine to optimal lattice constant, similar process of varying a and calculating cohesive energy and fitting it to BM equation to find the minimum point is repeated, now with different kpoints. The results are shown in table 2.

Table 2. Minimum cohesive energy at different kpoints – simple cubic

| kpoints | Minimum cohesive energy (eV/atom) | Difference with respect to highest kpoints (eV) |

|---|---|---|

| 35 | -8.194 | -0.040 |

| 56 | -8.176 | -0.022 |

| 84 | -8.209 | -0.055 |

| 120 | -8.157 | -0.003 |

| 286 | -8.154 | 0.003 |

It is seen that kpoints of 120 (15x15x15 grid) is the optimal value which gives the optimal lattice constant a as 2.637 Å and minimum cohesive energy as -8.157 eV/atom

3. Face centered cubic

Kpoints convergence is again performed for FCC structure and results are shown in table 3.

Table 3. Minimum cohesive energy at different kpoints – FCC

| kpoints | Minimum cohesive energy (eV/atom) | Difference with respect to highest kpoints (eV) |

|---|---|---|

| 56 | -8.659 | -0.004 |

| 84 | -8.643 | 0.012 |

| 110 | -8.655 | 0.000 |

| 120 | -8.655 | 0.000 |

The optimal kpoints as seen from the table, is 110 (10x10x10 grid) which correspond to lattice constant as 2.811 Å and minimum cohesive energy as -8.655 eV/atom.

4. Hexagonal closed pack

With two lattice constants a and c, the optimal values are found by fixing a ratio of c/a then perform similar curve fitting for minimum cohesive energy per atom.

First, ratio c/a of 1.50 is chosen to optimize in terms of kpoints.

Table 4. Minimum cohesive energy per atom at different kpoints – HCP

| kpoints | Minimum cohesive energy (eV/atom) | Difference with respect to highest kpoints (eV) |

|---|---|---|

| 3 | -8.691 | -0.026 |

| 14 | -8.681 | -0.016 |

| 36 | -8.665 | 0 |

| 76 | -8.664 | 0.001 |

| 136 | -8.665 | 0 |

With similar interpretation as above sections, kpoints of 36 (9x9x6 grid) is optimal in performing calculation for HCP structure. This kpoints will be used for different c/a ratio.

Figure 2 illustrate the BM equation fitting for different c/a ratio. The minimum for each fitted curve is then plotted against the c/a ratio in Figure 3.

It is observed from Figure 3 that c/a ratio of 1.65 has the lowest cohesive energy/atom which is -8.674 eV/atom and lattice constants of a = 2.817 Å and c = 4.648 Å.

Conclusions

It is interesting to see that the minimum cohesive energy per atom of HCP structure is lower than that of FCC structure, which suggest that Pt prefers the HCP structure and that does not agree with what is well known [9].

It is noted, however, that the minimum cohesive energy for each configuration is found by curve fitting to the BM equation. Hence to reaffirm the result, re-calculation was done in CASTEP for each of the crystal structure, using the determined optimal kpoints and lattice constants to reevaluate this discrepancy (table 5).

Table 5. Re-calculation for energy of each crystal structure

| SC | FCC | HCP | |

|---|---|---|---|

| a (A) | 2.637 | 2.812 | 2.817 |

| c (A) | - | - | 4.468 |

| Fitted minimum E (eV/atom) | -8.157 | -8.655 | -8.674 |

| Re-optimized E (eV/atom) | -8.207 | -8.664 | -8.605 |

From re-calculation results, cohesive energy per atom of FCC structure is the lowest, indicating the expected result of FCC structure being the stable structure for Pt.

Retrospectively, the convergence criteria for both kpoints and energy cutoff is ±0.01 eV, therefore a meaningful comparison can only be made if difference in energy between two structures is more than 0.02 eV. The difference between fitted minimum E of HCP and FCC is 0.019 eV (third row table 5), while that of the re-calculated energy is 0.059 eV (fourth row table 5). Therefore more confidence can be given to the re-calculated results.

A method that does not require re-calculation is to fit the BM equation multiple times to converge on a good cohesive energy value. This study, instead, calculated the minimum cohesive energy after fitting the BM equation only once to roughly determine the optimal lattice constant, then re-calculate the energy at that optimal lattice constant to use for comparison between crystal structures.

Lastly, the optimal lattice constant reported in literature [9] is 3.92 Å. For this study, converting primitive to conventional FCC yields a lattice constant of 3.98 Å. The relative error is 1.5% which is a very good agreement.

Reference.

[1] Sholl, D., Steckel, J., & Sholl. (2011). Density Functional Theory (p. 46). Somerset: Wiley.

[2] R.O Jones (2015), Density functional theory: Its origins, rise to prominence, and future, Rev. Mod. Phys. 87, 897.

[3] “First principles methods using CASTEP”, Zeitschrift fuer Kristallographie 220(5-6) pp. 567-570 (2005) S. J. Clark, M. D. Segall, C. J. Pickard, P. J. Hasnip, M. J. Probert, K. Refson, M. C. Payne

[4] J. P. Perdew, K. Burke, M. Enzerhof (1996). Generalized Gradient Approximation Made Simple, Phys, Rev. Lett., 77, 3865.

[5] D. Vanderbilt (1990), Soft self-consistent pseudopotentials in a generalized eigenvalue formalism. Phys. Rev. B 41 (11), 7892-7895.

[6] Franis Birch (1947), Finite Elastic Strain of Cubic Crystals, Phys. Rev. 71, 809.

[7] H. J. Monkhorst and J. D. Pack (1976), Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations, Phys. Rev. B 13, 5188.

[8] Jones E, Oliphant E, Peterson P, et al. SciPy: Open Source Scientific Tools for Python, 2001.

[9] Hermann, K. (2011). Crystallography and surface structure (Appendix E: Parameter Tables of Crystals). Wiley‐VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA.