In the May 1, 2014 on-line edition of “The Scientist” there was a short article entitled “Dog’s Worst Friend.” The article wasn’t about fleas or ticks or any other obvious parasites or pathogens that afflict our best friends. Instead, the article was about a kind of bacterium that every freshman biology student hears about in a deep, historical context of the Earth many billions of years ago.

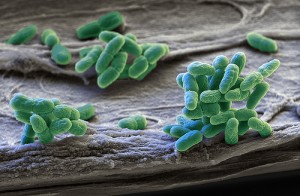

These bacteria are the “cyanobacteria” (the “blue-green algae”) a once incredibly abundant, aquatic, photosynthetic bacterium that two and half to three billion years ago was thought to have formed thick, floating, colonial masses of cells over almost all of the oceans of the world. These bacteria produced molecular oxygen as a wast product from their photosynthesis, and this oxygen changed both the Earth’s atmosphere and the direction of the evolution of life. It was these same cyanobacteria, about a billion years later that entered the cytoplasm of some of the newly evolving “eukaryotic cells” to form the symbiotic organelles of “green plant” photosynthesis, the chloroplast.

“The Scientist” article, though, didn’t talk about these freshman biology topics. The article was about present day cyanobacteria that occur, usually in small numbers, as a part of the rich, complex bacterial community of freshwater ecosystems that are found all over the Earth.

Many species of these cyanobacteria produce complex protein toxins. These chemicals were probably weapons used by the cyanobacteria in the intense, on-going chemical battle with other bacteria in their crowded, resource limited, aquatic habitats. Three billion years of competition and evolution would be expected to generate an incredibly diverse array of survival strategies, and the three to four hundred different, toxic peptides produced by cyanobacteria are not an unreasonable result of this time frame and competition matrix. Usually, cyanobacteria are a small, non-threatening part of the freshwater microflora. They can, however, under certain circumstances increase greatly in numbers and produce sufficient peptide toxins to sicken or even kill organisms like dogs, or sheep, or cattle, or even people!

“The Scientist” article talked about Harmful Algae Blooms (“HAB’s”) in freshwater lakes and ponds. It stated that the EPA has estimated that one out of every three freshwater lakes in the United States has the potential to have a cyanobacterial HAB, and that over the past decade of data collection 100 dogs are known to have died from cyanobacterial toxins that they encountered in some of these lakes.

The details about these lakes, the reasons for these outbreaks, and the nature of the toxic peptides, though, were not sufficiently developed in this article to really grasp the full scope of this problem. So, I poked around on the Internet and found a great article by Dr. Gregory Boyer, a professor at the SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry in Syracuse (that’s where Deborah and I went to graduate school!) entitled “Harmful Algae Blooms, a Newly Emerging Pathogen in Water.” Here’s the link: http://www.cws.msu.edu/documents/HarmfulAlgalBloomsWhitePaper_Boyer_Dyble.pdf

So what causes cyanobacteria in freshwater ecosystems to increase to potentially toxic levels? First and foremost the primary cause seems to be phosphate pollution. Phosphates are typically a limiting factor in aquatic ecosystems, so the addition of phosphates (from sewage or septic tanks, fertilizer runoff from agricultural fields or lawns, or from animal waste runoff) would have a large impact on the ecosystem. Cyanobacteria respond quite vigorously to added phosphates! Also, cyanobacteria need water temperatures above 20 degrees C (64 degrees F). Temperatures that warm can be generated in small shallow ponds fairly easily but will occur in larger lakes only at the end of a summer season. So, usually, large cyanobacteria blooms occur in the late summer!

There are a few other interesting features of cyanobacteria also come into play during a bloom: 1. Cyanobacteria contains gas filled, intracellular vacuoles (therefore they float!), 2. Cyanobacteria require high levels of sunlight to run their photosynthesis (therefore they NEED to be on the top of the water), 3. Cyanobacteria are not very high quality food sources for zooplankton (they tend to get left behind after feeding and grazing … maybe the peptides have something to do with this, too?), 4. Cyanobacteria clumped together into large colonies (which may be too large for most zooplankton to consume), and 5. Cyanobacteria can obtain the nitrogen they need to grow directly from the nitrogen gas of the atmosphere (they are “nitrogen fixers”).

So, the floating, clumped together masses of cyanobacteria when they get their population boost from the phosphates and the warm temperatures of the water (they are already making the nitrogen that they need!) tend to survive and accumulate in their ecosystems and crank out their hundreds of different toxic peptides! These toxins then can sicken and/or kill waterfowl, livestock, dogs, and even people! There is also a concern that chronic, low level ingestion of these toxins can lead to liver damage and even liver cancer in humans! Drinking water taken from surface water sources need to be checked for these dangerous bacteria!

Good control ideas that arise from those specific features of the cyanobacteria include stopping phosphate pollution (only use phosphate-free detergents!) and setting up fountains and bubblers in small ponds to break up any surface films and cycle the cyanobacteria to lower (and less optimal (colder and darker)) water levels.

In nearby Sewickley, Pennsylvania in 1975 there was a cyanobacterial contamination of the city’s drinking water. Sixty-two percent of the water system’s customers experienced gastrointestinal illnesses attributable to the toxins in the water. There are many historical events from all around the world in which humans or livestock or waterfowl were seriously harmed by cyanobacteria toxins.

So, when you and your dog go the local swimming hole (if such a thing still exists), if the water is scummy and smells bad, stay away from it! There are a lot of other things to do on a warm summer day!