(Click on the link to listen to an audio version of this blog … Bird and windows part 1

A 2019 study estimated that there are 7.2 billion birds in the United States and Canada. This is a large number, but it is significantly less than the 10.1 billion birds that were estimated to live in the United States and Canada just 50 years ago. Much of the decline in our avian populations is due to habitat loss, but two other, on-going factors (bird predation by cats and bird collisions with windows) may be steadily eroding bird populations and preventing many species from reestablishing their former population densities. These two factors are not at all trivial. Every year 2.6 billion birds killed by domestic cats in the United States alone, and over a billion birds each year in the United States die from collisions with windows.

The Audubon Society strongly recommends keeping cats indoors to try to reduce the carnage from their predatory habits. Even an over-fed, over-weight, lumbering house cat can do a great of damage to birds feeding or nesting on or near the ground! The window collision problem, though, is more complicated and does not have such an obvious solution.

When birds fly into windows the result is usually awful. A bird in flight “leads with its head,” and it is its head that typically slams directly into the window and bears the brunt of the damage from the force of collision. Necropsies of window-killed birds have shown that fractures of vertebrae or parts of the appendicular skeleton are much less common than severe soft tissue damage to the brain. A bird may be killed outright in its collision with a window or it may only be just momentarily knocked unconscious and seemingly “recover” enough to fly away. Often, though, that “stunned” bird has sustained such severe brain damage that it either dies soon after from its injuries or is unable to function to feed itself or avoid predators (like the omnipresent house cats!) and, thus, succumbs soon after.

Why do birds fly into windows?

The simplest answer to this question, and, possibly, the most accurate answer, is that birds simply don’t see the window glass. Birds do have wonderfully complex eyes, and, we infer, that using those complex eyes they generate very detailed and very precise visual fields. Bird eyes are larger relative to their body size than human eyes and have more kinds of “detail” photoreceptors (“cones”) on their retinas than humans. In addition to the blue, green and red cones that are seen in humans, birds also have cones that are sensitive to UV wavelengths! Further, birds have multiple areas on their retinas where these cones are concentrated to form very precise visual reception systems. Humans, on the other hand, only have a single cone-concentrated, high visual acuity area (the “fovea centralis”).

Also, in contrast to the cone structures of human retinas, many of the cones in bird retinas are paired together and most have tiny oil droplets that act as light filters. This filtration enables avian cones to be even more specific as to the particular wavelength of light that stimulates them. This gives birds a significantly more precisely tuned visual system than what is present in humans. But, they still can’t see window glass!

People often have trouble seeing glass windows and doors, too. I had a student a number of years ago on a field trip to Greece walk right into a glass door. She broke her nose and was very uncomfortable from the injury, but, at least, she had a tough enough cranium to avoid serious internal injuries!

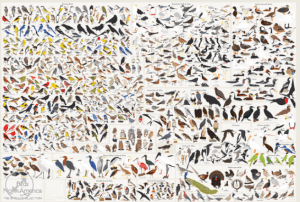

The total number of bird species on Earth depends on how finely you separate and distinguish species from subspecies and varieties (see Signs of Winter 1, December 16, 2021 and Signs of Winter 2, December 23, 2021 for a discussion of this species definition dilemma), but most estimates range from 10,000 to 20,000 species. Out of this diverse array of birds just under 1400 species are known to strike windows.

Why do such a small percentage of bird species strike windows, and why do these specific species of birds do so in very significant numbers?

The most obvious way to answer these questions is by recognizing that most of the diverse array of bird species do not live near people! Commonsense inferences are often quite misleading in science, but this one is incredibly accurate and insightful if not just a bit silly because it is so obvious: only birds that live near windows can fly into window glass! And, a useful corollary to this rule might be, those species that are most abundant near human habitations (and their windows) will be those species that most often strike windows and subsequently die from these collisions!

A study published in 2012 in the journal Wildlife Research by researchers at the University of Alberta outlined an order of observed bird/window strikes in an array of types of human habitations. The greatest number of strikes were seen in rural houses that had bird feeders while the second greatest number of window strikes were seen in rural houses without bird feeders. These observations reflect the greater number of birds in non-urban habitats and the “common sense’ rule outlined in the paragraph above, “where there are a lot of birds near windows, there will be a lot of collisions.”

The third greatest number of window collisions observed in this study occurred in urban houses with bird feeders, and the fourth greatest number of collisions observed occurred in urban houses without bird feeders. Finally, the smallest number of window collisions occurred in apartment buildings. These observations fit our “common sense” rule governing bird/window interactions.

What other factors besides simple abundance of birds near windows affects the number of window strikes?

The nature of the surrounding landscape can have an influence. Trees and shrubs near windows lead to more strikes. Bird feeders or bird baths (or other water sources) near windows lead to more strikes. Fruit bearing vegetation near a window lead to more strikes. Sheltered perches (favored by birds) near a window lead to more strikes. Interestingly, though, there is a very non-intuitive relationship between the distance the attractant is to the window and the probability of birds striking the glass. Any attractant that is three feet or less from the window does not lead to increased bird/window strikes, and any attractant that is more that three feet away from the window (even those that were ten feet or even twenty feet or more away) does lead to increased bird/window strikes!

The explanation for these observations involves how quickly a bird can go from a resting state to a flying velocity that generates sufficient momentum to cause significant brain damage in a window collision. Three feet, apparently, is too short a distance to allow fatal velocities and momentums to be achieved.

Supporting this momentum-strike hypothesis is the observation that slow flying birds (or at, least, birds whose initial flight velocities are fairly slow) are less likely to be killed in window strikes than more rapidly flying birds. These “slow” birds include rock pigeons, European starlings and house sparrows (and these last two species are in the very exclusive “one billion club.” Their huge worldwide populations may be maintaining themselves, at least in part, because of their relative immunity to window strike fatalities).

The relative location of the window glass (on the north, south, east or west of a house or building) does not seem to have a significant impact on the probability of a bird/glass strike. However, the history of a window’s location may have an impact. When a new house or building with windows is constructed, there can be a period of time over which a large number of bird/glass strikes occur. This is often due to non-resident birds, who have historically flown through a particular area, violently and unexpectedly encountering one of the new panes of glass. As these bird flocks “age out” (or die from fatal window strikes) these collisions become less and less frequent.

The density of building development has an impact on the probability of bird/window collisions. Buildings or houses that are closer together have fewer bird/window collisions. Houses in older neighborhoods tend to have more bird/window collisions probably because of the increased density of vegetation that typically surrounds older homes.

(Next week, we’ll continue this discussion and then describe some possible solutions to this problem!)