My story begins in high school. I was already set on becoming an entomologist and I had played my fair share of computer and Sega games while growing up. It was in high school when I was going back and forth between the real and virtual world that I had a realization that renewed my fascination, interest and love for the natural world.

Sophomore year of high school, I was addicted to a MMORPG (massively multiplayer online role-playing game) game. I was drawn into a world of made up digital trees, grass, ponds, buildings, resources, and creatures. What drew me? Curiosity, stories, artwork, the multiplayer social aspect, and the in-game competition for power – all paired with satisfyingly spaced leveling up and in-game reward thresholds.

Eventually I reached a saturation point. It took too long to reach the next levels, the world became too large, the story too drawn out, and perhaps there was too much to keep track of in the game. I grew bored and drifted away from playing that or any new video games. Additionally, my high school classes became more challenging and gaming didn’t seem to give me much of a real world tangible benefit.

A tree in the game is an artistic assemblage of pixels on a screen. The extent of its detail lies in its relationship to the story line and the time the animator had to create it. It is known, calculated, documented, and able to be reproduced.

When I visit a tree at my local park, I discover aphids, ladybugs, lace wing insects, pseudoscorpions, ants, robins, cardinals, and more. When I grab a microscope to further examine the organisms, the species list expands exponentially. The organismal community interacts and navigates in a way that likely could never be reproduced like the elements of a computer game.

They are yet to be calculated. They will never replay the exact same way. These organisms, their stories, morphologies, and puzzles have taken millions upon millions of years to form! And we’ve only begun, over the last couple hundred years, to study, document and create models of the natural systems – and even then, imperfectly.

There is so much we have learned and have yet to learn about the wild organisms around us. There exists a plant with a flesh that is better at healing burn wounds than any human manufactured ointment (Aloe). There are flies that fly in ways that humans are not yet able to replicate with technology (your common house fly). These are some of the most basic examples of the richness of the life around us. What else is out there waiting to be discovered? There are organisms out there whose lives are a tangle of exciting stories that you couldn’t even make up.

I believe that Pokémon Go can help connect people with this fascinating world. I downloaded and have been playing Pokemon Go this past month to check out the hype. As an entomologist, I was curious to see how this game, which was inspired by insect collecting, could affect peoples’ relationships with the nature. Might a side affect of this game that utilizes GPS location be that it connects gamers with the natural world?

This is not a game that can be played alone in your room at home. To make great strides in the game, Pokemon trainers have to get moving out the door to visit Pokestops, visit gyms, hatch eggs, and encounter wild Pokémon. So yes, the word ‘go’ is in the name of the game for a reason.

I like that the game does not require my constant attention as I walk and play. When I encounter a Pokemon, the game alerts me to its presence through a vibration or a sound. I am given plenty of time to tap to engage the Pokemon before it disappears.

Also a plus, the game does not captivate my full attention as I walk. When it comes to in-game visuals, the virtual game map has pleasing but basic, unchanging scenery as I move from one location to the next. Therefore, I have no reason for my eyes to stay glued on the screen while walking and playing so I am generally aware of my surroundings as I play.

I see the real world around me. I found a beautiful real life duck pond one day when I took a detour to visit a Pokestop. I saw ducks, frogs, and fish and appreciated how truly wild and distinct they are compared to the virtual Pokémon.

My feelings from high school return – I find the detail and depth of the real world refreshing after playing this video game. Do others experience this too?

Players are noticing, photographing, and sharing curious critters that they encounter as they play Pokemon Go. They post photos of their “real life Pokemon” encounters to social media. (Many of these are insects!) The hash tags #Pokeblitz and #PokemonIRL (short for Pokémon In Real Life) were created (by @BioInFocus ) to connect players with experts for identification help.

Down the line I think that virtual reality games have the danger of distancing people from the real world (as some computer games already have). However, I found that Pokémon Go strikes a nice balance of engagement. The more a player is out catching wild Pokemon, the more likely they are to encounter real wildlife too! The game exposes players, who might have otherwise remained inside the house playing games, to the natural world.

The popularity of this animal-capturing game, leads me to wonder if one day we will have a real animal version of this! Already we can take pictures of birds, insects or other animals and maintain a species list in a folder on our computers. One day will there be a game that keeps track for us?! One that lists the species and fills the slots with the photo and provides relevant information as we encounter each one? We already have a website and app that is close to filling this role – iNaturalist.

With iNaturalist any person can create an account and post a picture of an organism that they encounter. The program encourages the submissions of photographic observations with their associated date and location. Submissions are identified by the user or with help from other users. Some users have even discovered new species!

While iNaturalist is off to a good start, the app has far to go to attract a broader audience. According an article by NPR, the developers are trying to gamify iNaturalist. I am excited about this and will be keeping a tab on the their progress!

I like to think about how a Pokémon-like game that uses real wildlife encounters could operate with future technologies. Will animals, plants, and fungi we encounter be registered and added to our virtual player’s inventory in such a game? Might there be mixing of fact and myth to increase game appeal?

A solid method to confirm that a person actually encountered a particular species would be necessary for a successful game. Might wild birds, reptiles, and mammals be micro chipped and might we humans have a device that can read the microchip to electronically confirm that we encountered a particular species? What a world that would be. Would it help, hurt or maintain human and wildlife relations?

This leads me to think of evolutionary ecologist and conservationist, Dr. Dan Janzen’s vision of one day having a DNA reading gadget that is the size and cost of a hair comb, that can fit in your back pocket. His idea is that a person could have this in their back pocket whereever they go to unmistakably identify organisms. It would increase human “bioliteracy” – human understanding of the natural world because of increased accessibility to biological information.

A device like this could greatly contribute to the fabrication of a real world species checklist game. While this would assist with species identification and confirmation, it might it be dangerous for both wildlife and humans since obtaining DNA may require a close encounter and a snip of the organism for analysis. In some cases, a good reading would requre the entire organism, depending on the size. Still, I’m sure some combination of clever game design and future imaging technologies could overcome this animal welfare challenge.

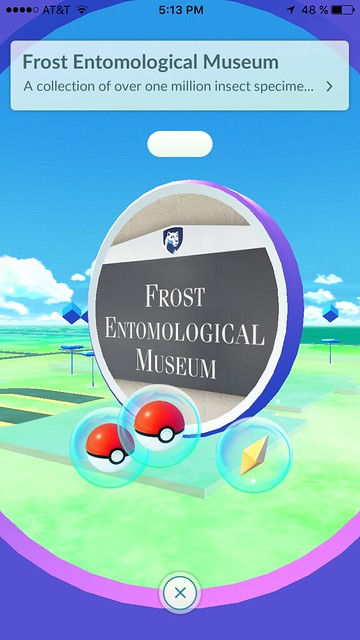

It would be remiss of me to not acknowledge the institutions with natural history collections which have already to a certain extent been trying to “Catch ’em all”. With there being so much biodiversity in the world, their collections contain impressive numbers of organisms. Each specimen provides valuable information about our planet at different points in time and place. The Frost Museum has 2 million insect specimens with more coming in each year. The Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University’s Entomology Collection contains about 3 to 4 million specimens and over 100,000 species, which is about 10% of the 1 million known species of insects. The U.S. National Museum’s Entomology Collection contains about 35 million specimens and over 300,000 species, which represent only 60% of the known insect families. There is work to be done to maintain the resolution of information in the collections and I can’t help but wonder if some of these Pokemon players could be converted into “PokemonIRL” collectors who contribute to their local natural history museums!