Men work at the Mudere mine near Rubaya, digging for manganese and other valuable minerals. (Image Source: Junior D. Kannah/AFP/Getty Images). In the public domain.

When the topic of doing business with Africa is mentioned, there is no doubt that the issue of conflict minerals must also be discussed. But what exactly are conflict minerals and what do they mean to US companies planning to do business with Africa or surrounding regions?

This question seems simple enough but in reality it is very confusing and even more difficult to identify and manage. In 2010 in response to providing comfort to the people of Africa being victimized, enslaved, and exploited by armed warlords and in an attempt to “weaken the militias by cutting off their mining profits”, the Dodd-Frank Act was introduced (Raghavan, 2014).

Additionally, due to an increased global need for minerals used in the manufacture of electronics and the belief that “exposing and cleaning up supply chains will reduce the stranglehold armed groups have on Congo’s mines”, Section 1502 was added to the Dodd-Frank Act. This section mandated that organizations listed with the US Securities Exchange Commission (SEC) must identify if they receive any minerals from a conflict region (Wolfe, 2015). Thus the definition for conflict minerals was created.

As defined by the Responsible Minerals Initiative (n.d.):

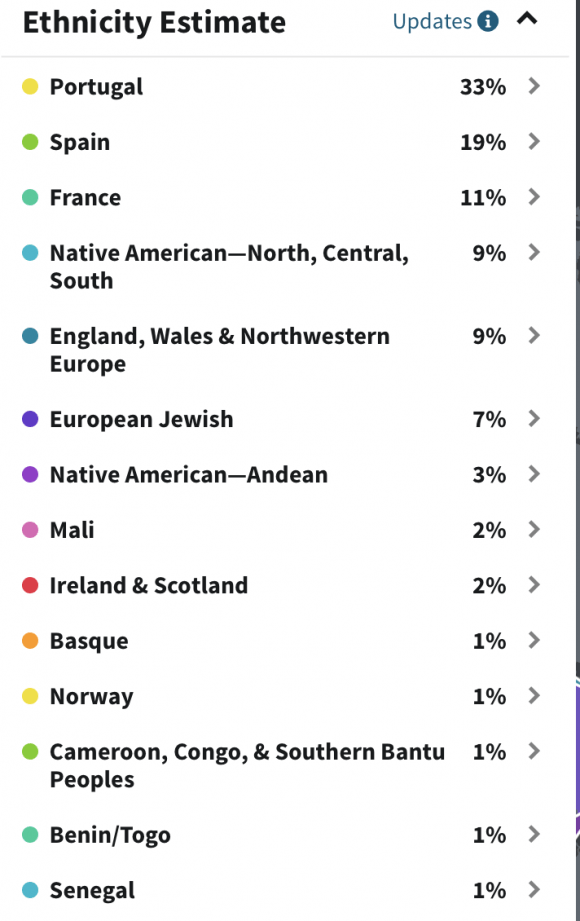

- US regulations identify conflict mineral as tantalum, tin, tungsten and gold. (commonly referred to as 3TG)

- These minerals are identified as being retrieved from any region that “directly or indirectly” supports warfare (often Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC))

- US Securities Exchange Commission (SEC) requires the registration and identification of all 3TG minerals specifically from the Congo

Although, lawmakers had good intentions, it is commonly believed that these regulations were not effective. Besides not being able to actually accurately trace the source of most minerals through a very complicated multi-level supply chain, the cost to attempt to provide this data is extremely expensive. Thus many companies actually just avoided buying any of these minerals and thus, the selling prices were greatly reduced. Hence, local workers and individual small mine owners were the people that had their livelihoods threatened (Raghavan, 2014).

Additionally, Section 1502 resulted in a “de facto ban on artisanal mining — miners relying on simple hand tools such as hammers and picks — in eastern Congo”. Once again this resulted in harming the hundreds of thousands of individual miners that relied on a daily wage to support their families. “As a result, entrepreneurial armed groups switched to alternative sources of income, such as timber, cannabis and palm oil” (Stoop, Verpoorten, & van der Windt, 2018).

So if the Dodd-Frank Act is really the failure that many experts believe it to be and actually has caused more harm than good to the individuals it was created to protect, what can the US & Africa do to correct their mistake?

- Africa needs to take ownership of their contribution to the issue

It is commonly known that Africa is a country steeped in poverty and chaos. However, this is not due a shortage of natural resources. This country has an abundance of assets including but not limited to diamonds, chromium, uranium, gold, cobalt, phosphates, platinum, manganese, copper, and bauxite. While the high levels of poverty have historically been blamed on Europe and the US, current African leaders are beginning to identify and acknowledge that Africa is also to blame for mismanaging their resources and causing their own misfortune (Moran, Abramson, & Moran, 2014, p. 533).

- Address the root cause of the violence in the Congo

“As other research shows, ending conflict in these regions requires systemic approaches that address the root causes of the violence”.

Experts have identified that in the violence in the Congo, can be associated mining of natural resources by only about 8%. The majority vast majority of fighting is actually a result of “long-standing political and economic grievances and disputes” (Stoop, et al., 2018).

- Engaging local leaders in the design of

Local politicians and lawmakers must be engaged in creating the policies and procedures to follow and also taking ownership of support these concepts to fruition. Suggested proposals from the European Network for Central Africa suggests “setting up reliable mineral-tracing systems, strengthening the public services that assist artisanal miners, providing technical and material assistance to mining cooperatives, and addressing the impunity of national military involvement in illegal mining” (Stoop, et al., 2018).

References:

Moran, R. T., Abramson, N. R., & Moran, S. V. (2014). Managing cultural differences (9th ed.). Oxford,UK: Routledge. ISBN: 978-0-415-71735-9

Raghavan, S. (2014, December 2). Obama’s conflict minerals law has destroyed everything, say Congo miners. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/dec/02/conflict-minerals-law-congo-poverty

Responsible Minerals Initiative. (n.d.). What are conflict minerals? Retrieved December 1, 2018 from http://www.responsiblemineralsinitiative.org/about/faq/general-questions/what-are-conflict-minerals/

Stoop, N., Verpoorten, M., & van der Windt, P. (2018, September 27). Trump threatened to suspend the ‘conflict minerals’ provision of Dodd-Frank. That might actually be good for Congo. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2018/09/27/trump-canceled-the-conflict-minerals-provision-of-dodd-frank-thats-probably-good-for-the-congo/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.8ddb1823162d

Wolfe, L. (2015, February 2). How Dodd-Frank is failing Congo. Foreign Policy. Retrieved from https://foreignpolicy.com/2015/02/02/how-dodd-frank-is-failing-congo-mining-conflict-minerals/