Brazil, with a land mass only slightly smaller than that of the US, a large population (sixth in the world), and the largest economy by far in Latin America (CIA Fact Book statistics), stands to grow economically, although in a relatively modest way, in the coming years. Interestingly, Moran, Abramson, and Moran point out that, while the United States is losing influence in Latin America, China is gaining influence by becoming one of the largest trading partners of South American countries, including Brazil.

Brazil, with a land mass only slightly smaller than that of the US, a large population (sixth in the world), and the largest economy by far in Latin America (CIA Fact Book statistics), stands to grow economically, although in a relatively modest way, in the coming years. Interestingly, Moran, Abramson, and Moran point out that, while the United States is losing influence in Latin America, China is gaining influence by becoming one of the largest trading partners of South American countries, including Brazil.

In 2009, China surpassed both the US and the EU to become Brazil’s largest trade partner. In 2015, China represented the largest importer to Brazil at 17.9% of imports coming from China, and in that same year, Brazil exported 18.6% of its trade to China. (CIA World Fact book)

My interest is in exploring the ways this mutually beneficial relationship has developed to its current state, as well as trying to uncover what national cultural dimensions may contribute to, or diminish, the ease with which the relationship has evolved. Is there more interest on the part of one country or the other? Or is it a bilateral effort?

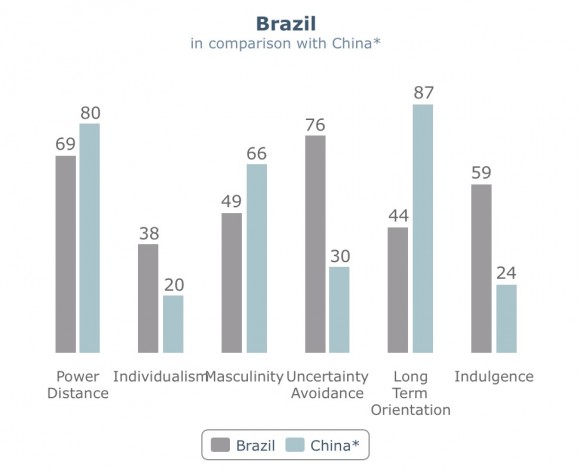

In reviewing Brazil and China and where they fall along Hofstede’s cultural dimensions, I hoped to discover similarities or differences between China and Brazil’s rankings in those dimensions that would explain an innate need or desire on the part of one or the other country to work together for mutual benefit–a cultural synergy of sorts.

Ultimately, the dimensions on which Brazil and China align and those on which they diverge may give rise to the activities Brazil is undertaking in its effort to court China, and may explain the willingness China has to embrace (if not make similar efforts in pursuit of) those forays.

China and Brazil are both collectivist cultures, according to Hofstede. Brazil has a score of 38 on the Individualism continuum which means that Brazilians are collectivist and likely to be integrated into strong, cohesive groups. At a score of 20 on the Individualism dimension, China is, similarly, a highly collectivist culture where people are more likely to act in the interest of the group, rather than in their own self-interest. Interestingly, Moran, Abramson, and Moran (p.406) dispute this notion, citing an anecdote by Pomfret in his book (p. 105) about a friendship between two young women–one American and one Chinese–that proves that individual characteristics trump cultural stereotypes. Nevertheless, the trend toward collectivism continues to be supported through the Confucian practice of ganqing–looking after one another’s interests ahead of one’s own (Moran, Abramson, Moran).

While this national collectivism could indicate a lack of desire to reach beyond one’s borders on the part of both countries, it seems Brazil has done so in spite of possibly an opposite innate desire to remain insular. We will continue to explore cultural dimensions to see what may be behind this.

On the dimension of Power Distance, China and Brazil are very closely aligned. At a score of 80 for China and a score of 69 for Brazil, both cultures reflect societal beliefs that hierarchy should be respected and inequalities among members of society are acceptable.

Thus, not surprisingly, Cardozo (2013, 2016) indicates that the relationship between Brazil and China has been heavily encouraged by President Lula (president of Brazil from 2003 to 2011) and, more recently, President Rousseff. The primacy of the presidency in Brazil, thanks to a cultural respect for hierarchy, means that, if the president makes the effort to engage deeply with another country, it is unlikely that the populace would find fault with these overtures.

Ultimately, though, says Guilhon-Albuquerque in his 2014 article about China, Brazil, and the US, “both Rousseff’s and Lula’s discourses are conspicuously silent about international politics and regional cooperation in matters other than trade, investments and global finance.” It seems that, regardless of the cultural similarities and differences between Brazil and China, the financial benefit of collaboration is adequately motivating for both countries.

One more interesting, and possibly telling, statistic about a cultural dimension not specifically measured by Hofstede: according to Transparency International, the two countries are not far apart in their business practices, measured according to the level of corruption they experience. Brazil is at 76 and China is at 83 on the corruption index. This is another aspect of doing business together that may make Brazil and China not odd bedfellows.

There is money to be made on both sides, the two cultures align on some important collectivist and hierarchy-bound dimensions, and Brazil has had a continuum of leaders interested in advancing the relationship with China.

References

Cardoso, D. (2013). China-Brazil: A strategic partnership in an evolving world order. East Asia : An International Quarterly, 30(1), 35-51. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org.ezaccess.libraries.psu.edu/10.1007/s12140-012-9186-z

Cardoso, D. (2016). Network governance and the making of Brazil’s foreign policy towards China in the 21st century *. Contexto Internacional, 38(1), 277-312. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org.ezaccess.libraries.psu.edu/10.1590/S0102-8529.2016380100008

Central Intelligence Agency. (2016). The world factbook. Retrieved from https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/

Guilhon-Albuquerque, José-Augusto. (2014). Brazil, China, US: a triangular relation?. Revista Brasileira de Política Internacional, 57(spe), 108-120. https://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0034-732920140020

Haibin, N. (2010). Emerging global partnership: Brazil and china. Revista Brasileira De Politíca Internacional, 53. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org.ezaccess.libraries.psu.edu/10.1590/S0034-73292010000300011

Pomfret, J. (2006). Chinese lessons: Five classmates and the story of the new China. Macmillan. Retrieved from https://books.google.nl/books?id=IlsCkove55YC&printsec=frontcover&dq=Pomfret+china&hl=en&sa=X&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=Socialist%20solidarity&f=false

Transparency International (2015). Corruption Perceptions Index, 2015. Retrieved from http://www.transparency.org/cpi2015