In our prior article in this series, we had discussed the origins of the political divide within the United States. Beginning with divergent opinions over how to interpret and implement the Constitution and the way our nation should be constructed, our first set of political parties – called by political historians the “First Party System” – consisted of the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans. The Federalists favored a strong central federal government that wielded a fair amount of power over the states and believed that the future of the nation rested in commerce, industry, and trade with foreign nations. The Democratic-Republicans believed in a very limited government, preferring the states to possess greater power, and felt that the yeoman middle-class farmer was symbolic of the direction the nation should follow. Despite making important changes in our government that influences us even today, the Federalists were repeatedly swept in elections following the presidency of John Adams. The party soon disbanded in 1828, ushering in the end of the First Party System and bringing on the Second.

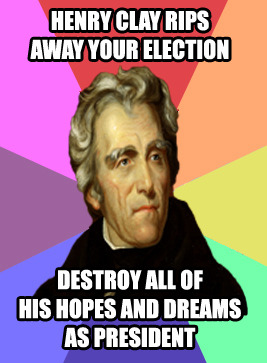

Oh, yes, Old Hickory would get his revenge…

In 1824, before the Federalist Party met its death, the seeds of the Second Party System were already planted. That year, only one party was in the presidential election. The Democratic-Republicans were running four men for the presidency: John Quincy Adams, Henry Clay, William Crawford, and Andrew Jackson. Jackson won the popular vote of the election, however there was no electoral majority. The election was then thrown into the House, which, with the behind-the-scenes help of Henry Clay, chose well-connected John Quincy Adams. Jackson, claiming a “corrupt bargain,” left the Democratic-Republicans to form his own faction of reformers. This faction would become known as the Democratic Party. Meanwhile, Adams’ Democratic-Republicans came to be known as National Republicans. Jackson’s party became known for its outspoken disapproval of the Second Bank of the United States, a large federally operated bank based on Alexander Hamilton’s Federalist beliefs. Jacksonian Democrats felt the bank, issuing its paper money, was perpetuating economic instability and that the credit of the United States should be based on specie (gold, silver, etc.) rather than paper notes. Furthermore, the Democrats ran in support of the working class, farmers, immigrants, and the westward expansion of the nation.

Ok, tell me that isn’t awesome.

The election of 1828 brought about an entirely new era of American politics, truly bringing a marked change from the First Party System. Jackson’s Democrats and Adams’ National Republicans unleashed into the country a level of mudslinging and negative campaigning previously unseen in the young nation. Jackson’s supporters referred to Adams as a pimp, spreading a rumor that while Adams was serving as ambassador to Russia, he had given an American girl to the czar for sexual favors. Adams’ supporters countered by calling Jackson a murderer for engaging in numerous duels and executing six militiamen during his military service. The National Republicans went so far as to question the legitimacy of Jackson’s marriage, claiming that Rachel Jackson was an adulteress because she had allegedly married Jackson while married to another man. Despite these less than sparkling aspects of this period in American politics, the election of 1828 sparked a huge overdrive in the levels of voter turnout. The heavy and highly involved campaigning during this election resulted in four times as many voters participating than in 1824.

An 1837 lithograph with the first usage of the Democratic “jackass,” a symbol of the Democrats that still exists today.

Jackson roundly defeated Adams and went on to a two-term presidency marked with what some would term as heavy-handed policy. Crushing the Second Bank of the United States, smashing political opponents like his rival Henry Clay, and presiding over the dangerous Nullification Crisis in which South Carolina threatened to secede over tariffs, Andrew Jackson gathered quite an opposition to his name. His opponents, rallying from the ashes of the old National Republicans, founded the Whig Party in 1833. The term “Whig” is derived from a term patriots and opponents of King George III in the American Revolution referred to themselves as. Wishing to announce their opposition to the oppression of “King Andrew,” the name stuck. Making their first major appearance on the national political stage in the election of 1836, the Whigs ran three candidates: William Henry Harrison, Daniel Webster, Hugh Lawson White, and Willie Person Mangum (what a name…). However, they were unable to muster up enough votes against the genius political maneuvering of “The Little Wizard,” Martin Van Buren. However, war hero Harrison managed to rally significant support and knock Van Buren down four years later.

In the next post, we’ll chart the second half of this rather large and influential segment of American political periodization, following the battle of the Democrats and Whigs, the rise and fall of smaller third parties, the divide over the question of slavery, and the eventual rise of the Republican Party. Thanks for reading, tune in next week!

,_2nd_president_of_the_United_States,_by_Asher_B._Durand_(1767-1845)-crop.jpg)