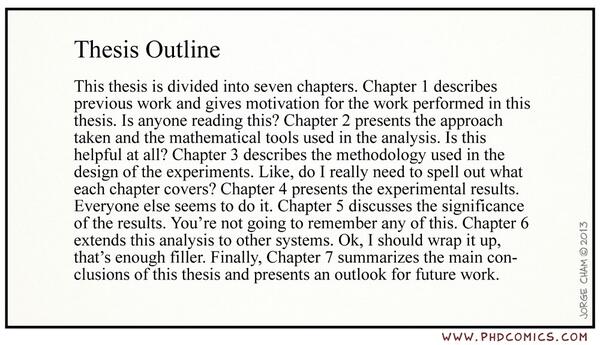

In this Beginning of the End five-part series, I have been breaking down important steps in the process of finishing up your PhD and offering advice for each of these steps. Just to quickly review… Part 1 discussed the importance of meeting with your thesis committee and what you should be talking about with them. Part 2 focused on drafting a thesis outline and going over this outline with your adviser. Finally, Part 3 was all about understanding the formatting guidelines for the thesis that are required by the Graduate School. That leads us to the fourth installment:

The Beginning of the End Part 4 of 5: WRITE WRITE WRITE! With some more on writing.

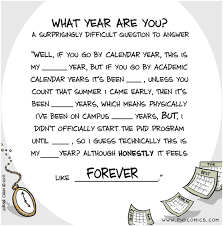

At this point you’ve met with your committee, drafted an outline, set up a defined timeline of your defense and when your writing should be done with your adviser, and downloaded the thesis template from the Graduate School. So now all you have to do is write a 100+ page document describing your research in its entirety — that shouldn’t be too bad, right? Ha.

At this point you’ve met with your committee, drafted an outline, set up a defined timeline of your defense and when your writing should be done with your adviser, and downloaded the thesis template from the Graduate School. So now all you have to do is write a 100+ page document describing your research in its entirety — that shouldn’t be too bad, right? Ha.

At this stage of a graduate student’s career, he/she has likely never written anything like a Ph.D. thesis before. For those who already have a masters degree and thus had to write a masters thesis, it might not seem as daunting, but for those who are like me, the largest documents I have had to write describing my research are grant proposals and manuscripts. Whatever your level of experience, odds are you have had at least SOME experience in science writing, so you shouldn’t feel totally helpless.

Like I have said in previous posts, I myself am just now going through this whole process, so I can only offer minor tidbits of advice. However, I have asked multiple graduate students and faculty for their thoughts, and here is the breakdown of advice for writing your thesis. I want to especially thank Dr. Sarah Owusu (Physiology), Dr. Josephine Garban (Molecular Medicine), and Dr. Liron Bendor (Genetics), all recent graduates from Huck Institutes’ programs, as well as Dr. Melissa Rolls, Chair of the MCIBS program, for their advice and help on these topics.

“Writing a thesis/dissertation is not all about having naturally good writing skills. Writing a thesis involves self-motivation, time management, finding your level of comfortability, and understanding that this is not an easy process that can be done alone.” –Dr. Sarah Owusu, recent graduate of the Physiology program

1. Carve out large chunks of time in your schedule to write

Writing your thesis isn’t something you can just do in your spare time between experiments. If you’re all done with your experiments, then this isn’t something you have to worry about, but for most of us, that won’t be the case. Schedule entire days or half days, depending on how your schedule looks, where you will be writing and let your adviser/labmates know that you will be unavailable during that time. If you don’t schedule in time to write, then you will likely find excuses to do something else because, let’s be honest, a lot of things are more fun than writing a thesis.

2. Figure out the best place for YOU to write

2. Figure out the best place for YOU to write

In order to help you stay focused on writing, you need to figure out the best place for you to be able to sit down and write without being interrupted. Generally speaking, your lab/office might not be the best place because people know they can find you there, and if you’re the most senior person in the lab, you probably already know that people come to find you multiple times a day. However, if that works for you, then do it! My personal favorite place to write is at home, but a lot of people might also find this distracting. At this point in your life, you probably already know what will work best for you, so find a place, and stick to it. Popular places to write include the library (on campus or downtown), a coffee shop, or Barnes and Noble.

3. Make deadlines for yourself

With a thesis defense date set, you know that your thesis has to be submitted to your thesis committee at least two weeks before that. However, coming up with smaller deadlines helps you to stay on track and stay motivated. Set up a schedule of when you will send your adviser certain chapters so that he/she is expecting them, which holds you accountable. This will also make getting edits back much easier rather than sending your adviser the entire thesis once you’re all done — trust me, I’m sure there will be LOTS of edits — so sending them different sections periodically will make both of your lives easier. Also, go over this schedule with your adviser ahead of time — he/she has a lot of other things to do other than reading your thesis chapters, so knowing their general schedule and having an idea of how long it will take for edits to come back will be useful. Finally, don’t be afraid to remind your adviser (via e-mail or in person) when you have sent him/her chapters so that your e-mail doesn’t get lost amongst the hundreds of e-mail he/she is getting every day.

4. Don’t forget to take breaks and find ways to reward yourself

In addition to setting deadlines/goals for yourself, find a way to self-motivate yourself by giving yourself a reward when you accomplish those goals. This could be watching a movie, hanging out with friends, eating your favorite treat, anything! Whatever it takes to make you work harder. You also need to be able to give yourself a break once in a while — taking a break to go for a walk/run, take a nap, or whatever it is that works best for you — will help clear your mind and allow you to work more efficiently. Just make sure your breaks/rewards don’t get in the way of you actually accomplishing your goals on time!

5. Find a writing buddy/group

Another way to help hold yourself accountable is to find a writing buddy or a group of writing buddies. Odds are you have friends or know of people who are writing their thesis at the same time as you, so set up times of when you will all meet up somewhere and write together. Another option would be to join the GPSA’s Thesis Dissertation Bootcamp they hold each semester.

Other important things to remember when writing your thesis:

1. Go back to your outline every so often to make sure you aren’t getting off-track — I imagine this is very easy to do, especially in the introduction!

2. When sending chapters to your adviser/anyone else who is reading your thesis for you, don’t just send them the first thing you wrote down. Take the time to self-edit your own work and at least check for spelling/grammatical errors. If you already have experience in science writing, chances are you already have experience in self-editing, too!

3. Make sure you are submitting a polished thesis to your committee — this means it includes all the necessary content that is written concisely and clearly, does not contain spelling/grammatical errors, and is in the correct format. The last thing you want to do is have your thesis committee walk into your oral defense thinking you are unprepared!

4. Remember that chapters can be a published or planned paper — this will save you a lot of time if the science/data has already been written! If you do this, make sure you clearly describe if the chapter is written from the paper verbatim, includes only part of the paper, or includes the paper plus more data. Also, if you did not write that published paper, you should not be copying it verbatim (that’s plagiarism).

5. That being said… DO NOT PLAGIARIZE. UNDER ANY CIRCUMSTANCES. EVER.