Posted on January 24, 2021

Burundian Elections During COVID-19

By Megan Soetaert

In countries throughout the world, the COVID-19 pandemic has created novel challenges in all aspects of governance, from healthcare to trade and many sectors in between. For some countries, like the small East African country of Burundi, the impacts of this pandemic have been exacerbated by preexisting political, economic, and social problems.

In Burundi, one area of governance where preexisting issues and the COVID-19 pandemic have collided is in their 2020 presidential elections. This article will examine the pre-COVID-19 political landscape of Burundi, Burundi’s response to the pandemic, and how the 2020 presidential elections were heavily impacted by COVID-19 before, during, and after Election Day in May 2020.

Pre-COVID-19 Political Landscape of Burundi

The political landscape of Burundi has been volatile for much longer than the duration of the COVID-19 pandemic. This country has faced political turmoil for decades, with potential progress in 2020 challenged by the global pandemic.

In May 2015, Burundi faced a military coup attempt against then-president Pierre Nkurunziza, who had been in power for ten years at the time and was seeking a third term.[1]Burundians across the political spectrum were unhappy with the president’s decision to seek a third term, which included a reinterpretation of the constitution on his part.

On May 13, 2015, General Godefroid Niyombare of the Burundian military declared Nkurunziza’s government dismissed, initiating the coup. This declaration sent citizens fleeing into neighboring states and caused splintering within the President’s party.[2]

Only two days later, Niyombare declared “that members of his movement had surrendered”, and Nkurunziza’s government declared that the coup had failed.[3] The effects of this attempted coup have lasted for years, further destabilizing the nation through violent demonstrations, political repression, and more.

However, in the early months of 2020, President Nkurunziza declared that he would not run for a fourth term in this year’s election, held in May. Nkurunziza’s ruling party, the National Council for the Defense of Democracy-Forces for the Defense of Democracy Party (“CNDD-FDD”), announced that the new candidate for their party would be Evariste Ndayishimiye, a proven Nkurunziza loyalist.

Although Nkurunziza had finally agreed to relinquish power, many Burundians feared that the move was purely symbolic and that he would continue to influence politics from the background.[4] Amidst a lackluster, damaging response to the COVID-19 pandemic (which reached the African continent in February 2020) and a questionable political climate, Ndayishimiye was elected the new President of Burundi in May 2020. The negative impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on contemporary Burundian politics and the presidential election will be discussed at length throughout this article.

COVID-19 Response in Burundi

The Burundian response to the COVID-19 has been problematic at best, endangering citizens and the functionality of the country. Since the first case of COVID-19 was recorded on the African continent in February 2020, former President Nkurunziza faced extensive critique for his administration’s response to the pandemic.

Nkurunziza made public statements insinuating that “divine protection” would be the primary protector of Burundian citizens against COVID-19, echoing other political and religious leaders in Africa. He also made the decision in May to expel the World Health Organization’s (“WHO”) country director for Burundi because of critiques that had been made against his government.[5]

In June 2020, Human Rights Watch was able to anonymously interview medical workers in Burundi regarding how the government was handling the virus. These professionals described how there were growing numbers of Burundians with COVID symptoms, but the central government refused to “carry out tests or adequately report on the pandemic,” limiting healthcare workers’ ability to help mitigate the effects and spread of the virus.[6]

Since the swearing in of the new President Ndayishimiye in June, Burundian medical workers are still wary of the government’s response to the pandemic, but positive changes seem to be occurring. In early July, Ndayishimiye’s administration announced new preventive measures and screening programs for COVID-19. Ndayishimiye also made a significant departure from his predecessor by publicly stating that the virus is “the worst enemy of Burundi.”[7]

From July to November, cases have risen in Burundi by over 500.[8] Although this may appear to be a negative development, the rise in cases actually represents an increase in testing. This has been made possible by a collaborative effort between the WHO, the Burundian Public Health Ministry, the East African Community, and a donation from the Chinese government.[9]

With the increased attention to public health measures (particularly in the capital Bujumbura) and increased cooperation with global partners, Burundi has finally begun taking steps in the right direction towards managing local effects of this global pandemic.[10]

2020 Burundian Presidential Elections & Impact of COVID-19

The political impacts of COVID-19 in Burundi have already been seen in the previous sections of this article – no aspect of society remains untouched by this global pandemic. Elections around the world have suffered because of COVID-19, with effects ranging from postponing elections, to election-related outbreaks, to operational challenges of non-traditional voting methods.[11]

Unlike some other African countries (like Kenya and Zimbabwe) who postponed their 2020 elections, Burundi (and others such as Guinea and Tanzania) went ahead and held presidential elections. According to everyday Burundians, health workers, and international parties, appropriate preventive measures were not taken when Burundians went to the polls, similar to other lower-income countries.[12]

Pre-Election Day Violence

The campaign process in Burundi that took place during the early months of COVID-19 was dominated by the sitting president Nkurunziza and his hand-picked successor, General Ndayishimiye, who later won the election. In the midst of a global pandemic, these leaders of Burundi decided to go forward with political rallies comprised of large, crowded groups of people not wearing face masks.[13] For many, these rallies were worth it to show their support for a transition of power- finally- even if the new candidate was a personal selection by Nkurunziza.

For supporters of the leading opposition National Congress for Freedom Party (“CNL”) and its presidential candidate Agathon Rwasa, political campaign rallies meant even more. Large rallies without COVID-19 safety measures were also held for Rwasa, similar to those for Ndayishimiye. However, the attendees at these opposition rallies faced more dangers than just the pandemic. SOS Medias Burundi, an independent journalist group, reported in May that there had been over 145 arrests of CNL party supporters in just a month of campaigning.[14]

A multiplicity of sources, ranging from local and international rights groups, journalists, the opposition, and the government published reports of increased violence in the leadup to the May 20 election day. Burundian journalists and non-governmental organizations cited threats of attacks by the ruling party and arrest by the police, being forced to decide between their safety and doing honest work. Burundian rights groups also reported increased attacks in April and early May.[15]

The opposition leader Rwasa described extrajudicial attacks and even killings of members of his party. The CNL party reported attacks and missing persons in the province of Ruyigi, a murder in the Mwaro province, and an arrest of a CNL legislative candidate.[16] In an interview with Voice of Africa reporters, Rwasa put the blame on the ruling party of Nkurunziza and Ndayishimiye, stating the violence was “meant to intimidate the opposition so as to guarantee the victory of the ruling party.”[17]

Even the Burundian government itself released statements about pre-election violence, including reports of two deaths and over twenty injuries. However, the ruling party appeared to place the blame on the opposition (the CNL Party in particular) for inciting violence and using hate speech in their rallies.[18]

Election Day and International Observation

Many Burundians- those who support the ruling party and those who do not- have anonymously voiced concerns regarding the legitimacy of the May 2020 elections. There were major concerns about the government silencing anyone supporting the CNL party, especially with popular social media and communication sites having faced blackouts on election day.[19] The lack of international observation was another major worry for many, and the belief that the ruling party controls the election process is prevalent throughout the country.[20] ; [21]

Although election monitoring and observation can happen in any country for any election, the United Nations and other international organizations have certain recommendations for international observation. According to a UN document from 2005, election observation is beneficial where “a significant proportion of the population may lack trust in the electoral system [and/or] countries with weak human rights records, or countries with extremely strong executive powers and long-time rulers”.[22] The 2020 Burundian election overwhelmingly fits these categories.

Unfortunately, Burundi went without any international observation of the monumental presidential election on 20 May 2020. The COVID-19 pandemic was the official reason for the lack of observers in the country, with the government having suspended passenger flights into the country on 22 March and implementing a 14-day quarantine period for many travelers entering Burundi.[23]

In May, the enhanced COVID-19 public health measures, see supra, had not yet been implemented, and the major rhetoric from the government was that of divine protection from the virus. This led many Burundians- and outside observers- to believe that the ruling party may have been using the pandemic as an excuse to retain tighter control over the election process by making the entry process for observers more difficult or even impossible.[24]

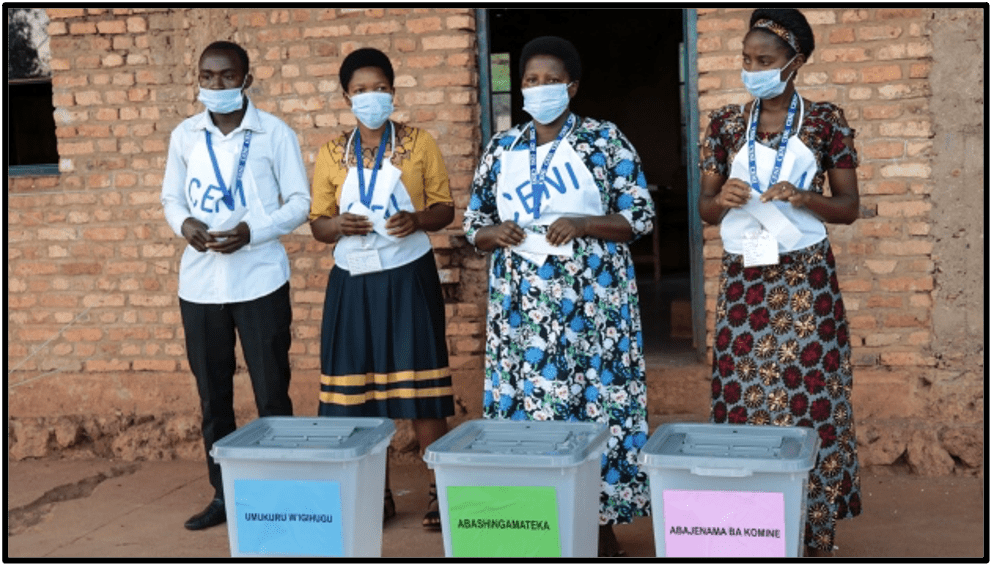

Further reinforcing this public belief are reports from Election Day at polling stations. The New York Times received reports of long lines of Burundian voters “standing shoulder to shoulder without masks or gloves”. The NYT also spoke with health ministry workers who said “voters were asked to wash their hands while poll workers donned masks and gloves. But temperatures were not checked because there was not enough money to buy equipment.”[25]

The major regional organization in East Africa, the East African Community (“EAC”), has been heavily invested in Burundian peace for many years. As early as February, it had been seriously preparing two election observation missions to Burundi; a long-term mission to stay before, during, and after Election Day, and a short-term mission to monitor polling activities.[26]

As stated in a press release in February, the EAC has “deployed Election Observer Missions to all its Partner States who have gone through elections over the years.”[27] According to the Secretary General of the EAC, this is to help promote democratic governance in East Africa, to enhance confidence in the election process, and to reduce electoral violence.[28]

The EAC did not issue a press release when the Burundian government announced on 8 May that anyone entering the country, including EAC observers, would have to face a two week quarantine that would extend past the election date.[29] However, the EAC was not able to send observers into Burundi to monitor the 2020 election, a considerable letdown for Burundians and outsiders invested in the election.

Election Results

Unlike the 2015 elections- in which Nkurunziza was guaranteed the win- Burundians had a more legitimate range of choices on 20 May 2020. The polling process was much more peaceful than five years ago, with the lack of proper COVID-19 social distancing and masking procedures more of a public safety risk than electoral violence.[30] ; [31]

Five days after Election Day, on 25 May, the Independent Election Commission (whose independence has been called into question throughout the electoral process) declared the ruling party candidate Ndayishimiye the winner with 69% of the vote.[32] CNL opposition leader Rwasa was officially counted as the runner up with 24% of the vote, although the party quickly made claims of foul play by the government and election commission.[33]

These claims were taken to the Burundian Constitutional Court, which upheld the initial election results as legitimate in the first week of June. However, like the Independent Election Commission, the legitimacy of the court has been called into question by civil society groups.[34] Surprisingly, Rwasa backed off from his aggressive position and accepted the Court’s decision. In an interview with Voice of Africa, he said “The CNL party will respect what the law says by doing what the law allows us to do. Also, we will monitor the new leaders to see where they will take the country.” [35]

The data is not completely clear whether or not there was a spike in COVID-19 cases after the May elections. According to the World Health Organization, Burundi reported no new cases from 19 May, the day before the election, to 1 June, when 21 new cases were reported.[36]This lack of data in the days following the election is likely due to government neglect of public health, not an actual lack of spread. This holds considerable weight when considered alongside reports describing the lack of protective measures at polling locations.[37]

On 9 June, only a week after the Constitutional Court’s decision regarding election results, the world was shocked to hear that the outgoing president, Nkurunziza, died of cardiac arrest.[38] Alongside the initial shock of the 55-year-old president’s sudden death, a number of sources reported many questions arising about the nature of his illness.[39] Multiple reports have been released saying that Nkurunziza may have actually been infected with COVID-19. The BBC stated that SOS Medias Burundi received reports from medical and government sources that he did, in fact, have the virus, although none of these reports have been confirmed.[40]

Nkurunziza’s Death

The culmination of a volatile political environment, the COVID-19 pandemic, the May 2020 presidential elections, and the death of outgoing President Nkurunziza in June put Burundians and their country in a challenging place this summer.

After the president’s unexpected passing, the Burundian Constitutional Court quickly decided that President-Elect Ndayishimiye’s inauguration should take place as soon as possible in order to avoid political troubles.[41] Ndayishimiye was sworn in as the President of Burundi on 18 June 2020, just nine days after the former president’s death.

Burundians of all political ideologies, as well as the international community, are still waiting anxiously to see how Ndayishimiye will lead the country. There is hope that he will depart from Nkurunziza’s oppressive governing style and create a more peaceful and open Burundi.[42]

One positive development that has already been seen in Ndayishimiye’s administration is his willingness to implement real steps to combat the spread of COVID-19. Although there was not sufficient social distancing or wearing of face masks at his inauguration, his administration has since officially stated that they are “determined to fight the spread of COVID-19.”[43]

In the first few weeks of his term, Ndayishimiye declared COVID-19 a threat to Burundi, promised to implement mass screenings in cities with existing cases (programs which began in early July), and promised to lower the cost of soap and water.[44] Furthermore, Burundi’s health minister has created stronger COVID-19 guidelines, including personal protective equipment requirements for guests and workers in hospitals and in public transportation such as taxis.[45]

The World Health Organization Coronavirus Disease Dashboard reports much more frequent testing occurring in Burundi since 9 July 2020.[46] Although this corresponds to an increase in reported cases—642 as of 20 November 2020—it is a positive development as cases were likely underreported beforehand.

Conclusion

President Ndayishimiye has a long, challenging road ahead of him if he plans to make positive changes in the small East African nation of Burundi. The compounding effects of previous (and potential) political unrest, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the death of Nkurunziza will not make this any easier. However, if the recent developments in how the new administration is handling COVID-19 are any indication—and if political cooperation is prioritized—Ndayishimiye just may have a chance at leading Burundi in a positive direction going forward.

[1] Burundi: The May 2015 coup attempt, including its instigators, how it unfolded, the violent incidents and the outcome; the treatment of the coup instigators by the government, Imm. and Refugee Board of Canada. (Oct. 30, 2015), available at https://www.refworld.org/docid/568fc3474.html.

[2] Nina Wilén, The Rationales behind the EAC Members’ Response to the Burundi Crisis, 17 G. J. of Int’l. Af’s. 70 (2017), available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/26396155.

[3] Supra note 1.

[4] Chrispin Mwakideu, Burundi: Is President Pierre Nkurunziza ready to relinquish power?, Deutsche Welle(Jan. 27, 2020), available at https://www.dw.com/en/burundi-is-president-pierre-nkurunziza-ready-to-relinquish-power/ a-52164843.

[5] Eloge Willy Kaneza, Burundi starts taking COVID-19 seriously, begins screening, Associated Press (Jul. 6, 2020), available at https://apnews.com/article/3e6ef0e411214dbd4432b10bdb7d85ef.

[6] Burundi: Fear, Repression in Covid-19 Response, Human Rights Watch (Jun. 24, 2020), available at https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/06/24/burundi-fear-repression-covid-19-response#.

[7] Supra note 5.

[8] Burundi Situation, World Health Organization (Nov. 11, 2020), available at https://covid19.who.int/region/afro/country/bi.

[9] Burundi: Laboratory assistants trained thanks to donation from China, World Health Organization (Aug. 11, 2020), available at https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/burundi-laboratory-assistants-trained-thanks-to-donation-from-china.

[10] Supra note 1.

[11] Darren Taylor, How COVID Is Affecting Elections in Africa, Voice of Africa (Jun. 3, 2020), available athttps://www.voanews.com/covid-19-pandemic/how-covid-affecting-elections-africa.

[12] Id.

[13] Rodney Muhumuza, Ignatius Ssuuna, Burundi defies COVID-19 for election ending a bloody rule, Associated Press (May 16, 2020), available at https://apnews.com/article/540a6cb0d64f38cec2692e617d76dffc.

[14] Id.

[15] Reuters Staff, Impoverished Burundi, battered by violence and coronavirus, gears up for elections, Reuters (May 16, 2020), available at https://www.reuters.com/article/us-burundi-election/impoverished-burundi-battered-by-violence-and-coronavirus-gears-up-for-elections-idUSKBN22S09N.

[16] VOA News, Burundi Opposition Leader Says Party Members Attacked in Run-up to Elections, Voice of Africa (May 8, 2020), available at https://www.voanews.com/africa/burundi-opposition-leader-says-party-members-attacked-run-elections.

[17] Id.

[18] Id.

[19] Burundi election: Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp blocked, BBC News (May 20, 2020) available at https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-52737081.

[20] Supra note 13.

[21] Supra note 16.

[22] Women and Elections, United Nations (Mar/ 2005), available at https://www.un.org/womenwatch/osagi/wps/publication/WomenAndElections.pdf.

[23] COVID-19 Measures in Member States, COMESA (Oct. 2020), available at https://www.tralac.org/documents/resources/covid-19/regional/4139-covid-19-measures-in-place-in-comesa-member-states-24th-edition-2-october-2020/file.html.

[24] Supra note 13.

[25] Abdi Latif Dahir, Burundi Turns Out to Replace President of 15 Years, Pandemic or No, N.Y.T. (May 20, 2020), available at https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/20/world/africa/burundi-election.html.

[26] EAC readies to deploy Election Observer Mission to Burundi General Elections slated for May 2020,East African Community (Feb. 10, 2020), available at https://eac.int/press-releases/1668-eac-readies-to-deploy-election-observer-mission-to-burundi-general-elections-slated-for-may-2020.

[27] Id.

[28] Id.

[29] Supra note 13.

[30] VOA News Staff, Burundi Counting Votes in Presidential Election; Opposition Alleges Fraud, Voice of Africa (May 21, 2020), available at https://www.voanews.com/africa/burundi-counting-votes-presidential-election-opposition-alleges-fraud.

[31] Christina Golubski, Africa in the news: Burundi, Benin, South Sudan, and COVID-19 updates, Brookings Institution (May 23, 2020), available at https://www.brookings.edu/blog/africa-in-focus/2020/05/23/africa-in-the-news-burundi-benin-south-sudan-and-covid-19-updates/.

[32] VOA News Staff, Ruling Party Candidate Wins Burundi Presidential Election, Voice of Africa (May 25, 2020), available at https://www.voanews.com/africa/ruling-party-candidate-wins-burundi-presidential-election.

[33] Id.

[34] Frederic Nkundikije, Burundi Politicians Broadly Accept Ruling Party’s Win in Presidential Vote, Voice of Africa (Jun. 9, 2020), available at https://www.voanews.com/africa/burundi-politicians-broadly-accept-ruling-partys-win-presidential-vote.

[35] Id.

[36] Burundi, World Health Organization (Nov. 13, 2020), available at https://covid19.who.int/region/afro/country/bi.

[37] Supra note 25.

[38] Nkurunziza death: Burundi court rules to end power vacuum, BBC (June 12, 2020), available at https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-53024079.

[39] Burundi: Pierre Nkurunziza’s death marks the end of an era, Amnesty International (Jun. 17, 2020), available at https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2020/06/burundi-pierre-nkurunziza-death-marks-the-end-of-an-era/.

[40] Supra note 38.

[41] Id.

[42] Supra note 39.

[43] Supra note 1.

[44] Id.

[45] Id.

[46] Burundi, World Health Organization (Nov. 20, 2020), available at https://covid19.who.int/region/afro/country/bi.

Follow Us!