The truly gifted teacher is one who says back to you what you are hoping to say. But better. Or rather, in the way you wish you had said it originally, because now you recognize what it is you thought you were saying.

In that uncanny moment of exchange, when you both do and do not recognize your own words, the boundaries between what you thought you knew and what you are beginning to know become confused in a way that is, well, uncanny, and you are both was and not yet simultaneously. As Carla Freccero might say, Queer time is out of joint.

You don’t need to know what you want to say before you begin saying it; the insight develops in the saying. It is what in Composition is called “writing to learn,” and it is the one thing I most hope my students take from me — that writing is a way to dis-cover the new thought rather than to put forward the already known.

“There are times in life when the question of knowing if one can think differently than one thinks, and perceive differently than one sees, is absolutely necessary if one is to go on looking and reflecting at all.”

Michel Foucault, History of Sexuality, Vol. 2 (New York: Vintage, 1990)

For literally decades now, I have been working both with and against queer anti-social theory, the idea that what the term queer tries impossibly to represent is the negation (and not the erasure) of the normal (one argument being that, if the norm is the statistical average, it cannot be dispensed with, at least not in the present; we cannot easily unthink statistics. We can of course make an argument against a particular set of statistics, or even statistics as a measure of value, but that is not quite the same as unthinking them, never mind dismantling the many institutions that have adopted this disciplinary technique.)

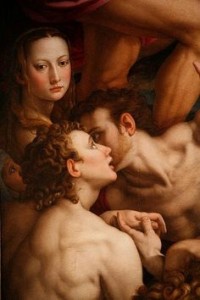

From Leo Bersani, I grabbed the idea that, in his famous phrase, “sex might be a tautology for masochism.” But, at the same time, I have been fascinated by Deleuze’s rewriting of masochism and troubled by both Bersani’s and Lee Edelman’s employment of the concept of the death drive and the idea that one might “embrace” the unconscious.

My compromise has been to employ the notion of the anti-Oedipal in the sense of the undoing of Oedipus — that is, the deconstructing, in the rigorous sense of the word, of the boundary between the small human animal and the human being. Devolving. Working to undo processes of subjection and subjugation that produce gender and sexuality as the binaries male/female in the first instance and heterosexual/homosexual in the second. Contrary to some critics of the anti-social argument, this is not to grant gay men a privileged epistemological position. Experimentation with the boundaries of an always historically contrived body is not limited to a particular social identity.

This position melds psychoanalytic notions with Foucauldian accounts of the subject and Deleuze’s masochistic aesthetic. Perhaps incoherently.

Recently, I’ve been reading Stephen Sharot’s work on Jewish antinomianism (which is not, as Sharot cogently argues, the same as nihilism).

Looking at two antinomian traditions, one identified with Freud and the other with Durkheim, Sharot asks, “Is antinomianism an expression of man’s basic sexual and destructive drives in revolt against the constraints of society, or is it a product of processes of learning and socialization within particular social and religious milieus? Is antinomianism a product of a normally latent but unalterable human nature, or does it demonstrate the phenomenal modifiability of human nature?” (124).

His argument suggests that the anti-social debates should be understood as the product “of conflict and tension between two or more sets of socially produced phenomenon” (137, emphasis mine). In other words, he rejects both the ahistoricity of Freud and a version of Durkheim’s sociology that risks the volunteerism of “Don’t like society? Change it!” The neoliberalist mantra: everything is a choice, and one made possible by the free market; everything is a matter of individual responsibility.

My argument rests on the assumption that the attraction to the de-gradation of the self is not the same as the desire to harm — either oneself or an other. Also, that the pursuit of an ecstatic loss of boundaries is quite logically figured in a phallocentric culture as the act of demanding to be penetrated and the desire for contact with menstrual fluids, for example.

This position holds up as a model the most culturally degraded form of sexual pleasure. It assumes the mobility of fantasy, the pleasures of cross-gender identifications, and the potential to rearrange, even if only temporarily, the approved linkages between body and subjectivity.

Unfortunately, we live in a world where phallocentrism reasserts its prerogatives via rape, a world where there is so much violence that we fear even to talk about the fantastic possibilities of the loss of boundaries, where the prevalence of sadism — understood here as the pleasure of destroying the other — is all too present. (One of the crucial differences between Freud and Deleuze: while Freud sees masochism and sadism as complementary perversions, Deleuze argues that the two represent two different perversions and accompanying aesthetics. The masochist seduces the other into being the top; the sadist’s pleasure feeds off of the unwillingness of the other. Not the feigned unwillingness of two people engaged in a game of consent, but the violation of the will of the other.)

My various forms of privilege make it possible for me to experiment with fantasies of de-gradation. But I have been fag-bashed and bullied, shamed. In other words, I understand that a certain privilege is alleged to be operating in my desire to undo myself. But this claim assumes in advance that I have typically experienced myself as the intentional subject. And that ain’t so. (See my Coming Out Again, Queer OCD.) Perhaps because stigmatized subjects have contradictory investments in the ego, they are more open to its shattering and less traumatized by the possibility of “losing it.”

It is the nature of fantasy that it has a relationship to the real but sustains itself in the failure to achieve that real. Fantasies always combine the unconscious and conscious, known and unknown, willed and unwilled (or willed “against” oneself). This is what makes sex so pleasurable and so scary. Up to this point, but no more. Which is why being a top is a huge responsibility.

I anticipate the reading of my position as weirdly un-Foucauldian in that I am not yet ready or willing to free myself from sex, channeling the Augustine of Hippo who said, “Lord, grant me chastity and continence, but not just yet.”

In the course of writing these musings, I came across this very recent psychoanalytic account of the value of the perverse:

“What qualifies a sexual act as perverse is not the precise script enacted but that transgression and interembodiment work in tandem. The former lures the self into crashing through its own regulatory walls, one’s idiosyncratically sutured line of prohibition: the latter inundates the subject with new undecipherable messages from the other (What does this person want from me? What did that look/gasp/touch mean?). ”

“Sexual contact . . . places one in a force field of copious enigmatic messages directed at us by our sexual partners. By invoking the body, the site where the tangle of this kind of normative human enigma has originated, it showers us anew with the other’s undecipherable message. This is what makes perversion an ideal site for the evocation of limit experience and the dissolution of the self.” Avgi Saketopoulou, “To Suffer Pleasure: The Shattering of the Ego as the Psychic Labor of Perverse Sexuality,” Studies in Gender and Sexuality.

Other writers who have deeply shaped my thinking on anti-social theory: Elizabeth Cowie, Lynne Segal, and Candace Vogler. For a brilliant effort in Italian to read, minus historicism, queer Italy’s genealogical relationship to the queer antisocial debates, see Lorenzo Bernini’s Apocalissi Queer. Reading Bernini, I was reminded that I needed to add Guy Hocquenghem to the trajectory of my thinking, as well as Bataille.

Bernini’s reading also reminds us of something that should be self-evident: the goal of psychoanalysis is, and was, to alleviate human suffering. His comments on ambivalence have got me thinking about the relationship between a refusal of ambivalence and heteronormativity, as well as the way melodrama is a means whereby we might “live,” on a fantastic level, our ambivalence — minus feelings of shame that arise from our knowledge that we just cannot seem to conform to the model of “two become one.”

About Queer Optimism, however, I remain unconvinced, precisely because it assumes in advance the subject I have never been (nor particularly desire to be). There was never a before, for example, when my gender fit and I was not shamed because of it. (That the author subscribes to ego psychology is obvious; that he does not acknowledge its critique is unfortunate.) But it is also that queer child who believed he did in fact have a future.

I have always been disturbed by the failure of some of the theorists I most admire to entertain the suggestion that there might be something compulsive in the effort to free oneself from the I, and that this compulsion may be, for some, a source of pain.

I understand, strategically, the refusal to pathologize the sexual behavior of others. I also realize that there is a certain amount of “necessary” pain in self-shattering. But, thinking again about Bernini’s recent work, I am struck by the way in which any ambivalence about anti-social being can be written off as false consciousness or resistance. Such a position inscribes psychoanalysis as the law of the father — a self-defeating gesture, at least for a feminist psychoanalysis.