“I’ll bet you that nine out of ten people, if they see a woman across the courtyard undressing for bed, or even a man puttering around in his room, will stay and look; no one turns away and says, “It’s none of my business.” They could pull down their blinds, but they never do; they stand there and look out.” – Alfred Hitchcock

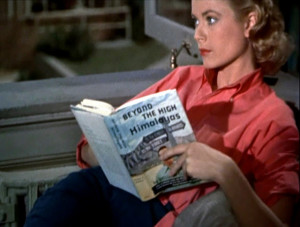

Rear Window is what Hitchcock likes to call a suspense thriller. He specialized in this genre as he believed that drama is life with the dull bits left out. This movie is a great example of a voyeuristic film that emphasizes the pleasure of looking. We get to see the view through the eyes of Jeffries the voyeur which is important in the plot of the movie as we saw. By definition, voyeurism is the practice of obtaining sexual gratification by looking at sexual objects or acts, especially secretively. Many other movies focus on the subject of looking and voyeurism, the motivation behind it and the consequences that come with it. Two of the more popular movies (that I have actually seen) with this focal point are American Beauty and Psycho.

The movie American Beauty uses Ricky Fitts as a voyeuristic character. The audience is often given the opportunity to look through his camera to give us the viewpoint of Ricky, the voyeur in this movie. He sees beauty in the little things in life, such as a plastic bag drifting away. The way in which Ricky sees life is as if he appreciates all of the beautiful things in life that others might not acknowledge since they are caught up with fitting in with the suburban stereotype-much like Jane, his love interest. He finds the beauty of Jane and films her through his window which shows his sense of voyeurism.

The movie “American Beauty”, directed by Sam Mendes and written by Alan Ball. Seen here, Wes Bentley as Ricky Fitts. Initial theatrical wide release October 1, 1999. Screen capture. © 1999 DreamWorks. Credit: © 1999 DreamWorks / Flickr / Courtesy Pikturz.

Image intended only for use to help promote the film, in an editorial, non-commercial context.

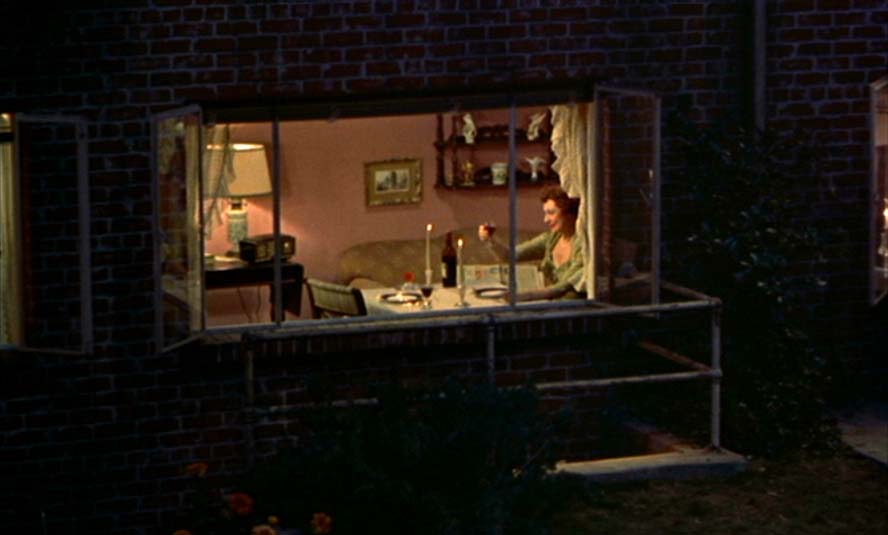

Psycho is another example of Hitchcock using a voyeuristic character, Norman Bates, to show the ‘pleasure of looking’. This movie is unique because it actually affirms the fact that us as viewers are merely voyeurs as well. Specifically, one example of this is shown in the photograph below when we are given the image through the eyes of Norman. By making Norman’s gaze and the gaze of the audience the same, Hitchcock gives the chilling realization that we as viewers and voyeurs could possibly be given some of the blame for Marion’s death.

** The A&E TV show, Bates Motel is based off of Psycho. (10/10 I would indeed recommend.)

RUN DMC said it best, “Tinted windows don’t mean nothin’, they know who’s inside.” So readers beware, you never know if there is a voyeur in your life. You also never know the terror (or beauty) that could be hidden in the simplicity of the everyday.

Check out this list of 10 voyeuristic films!

http://whatculture.com/film/10-films-about-voyeurism.php/5