UPDATE: This blog post is available as a pre-print at bioRxiv:

Mikó, István & Andrew R. Deans (2014) . The mandibular gland in Nasonia vitripennis (Hymenoptera: Pteromalidae). doi: 10.1101/006569

Nasonia vitripennis (Hymenoptera: Pteromalidae; Jewel Wasp) is the most researched parasitoid in the model organism/genomic world. The reason for that, in part, is the easy handling of Nasonia cultures (you can order one from here for a few bucks), the small body size, and its very short developmental period. While it attracts genomic people to study gene function and to test findings from Drosophila, these minute wasps are really interesting in other ways as well. They are among the few organisms where males attract virgin females. They do this with a pheromone—(4R,5R)- and (4R,5S)-5-hydroxy-4-decanolide (HDL)—that is a product of the rectal gland (Steiner & Ruther 2009).

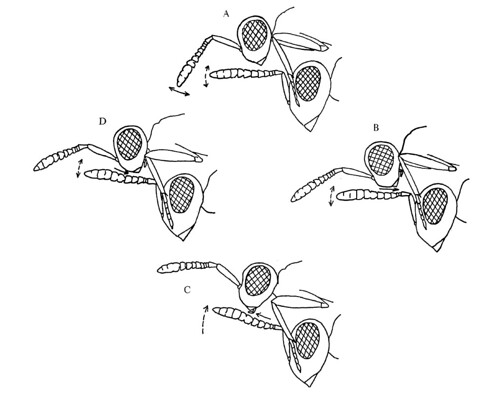

There is another, perhaps even more exciting but certainly way less known behavioral component of Nasonia males that is related to the activity of a second pheromone producing gland in males. Van den Assem and colleagues have performed some really amazing experiments on these small wasps (e.g., van den Assem et al. 1980) that, as far as I know, have never ever been repeated and thus their findings never confirmed. Barrass (1960) first described a unique courtship position for male Nasonia vitripennis specimens:

The male’s head is above and between the female’s erect antennae and its mandibles are very near to the proximal region of the female’s flagella. In this position (Figures i and 2A) the antennae are held above and anterior to those of the female. Following this the male’s head moves downwards slightly (Figure 2B), and then it is raised so that the mouthparts are near to the distal region of the female’s flagella.

The courtship head movement, later named as head nodding by van den Assem and his colleagues is a unique behavior of Nasonia males that might actually improve the discharge of an enigmatic sexual pheromone, an aphrodisiac (see smartbox).

|

Although uncommon, aphrodisiacs do occur in numerous insect taxa. They have been reported from many Lepidoptera, Dictyoptera, Orthoptera, and Heteroptera (Butler 1967) and are usually produced by males for preparing the female for copulation, after the couple has been brought together by olfactory sex attractants and/or other means.

van den Assem and colleagues hypothesized that a putative pheromone is produced by the male during courtship that has aphrodisiac effect, and that perhaps it is related to the nodding movement of the head. In the their experiments the researchers combined the following treatments: (1) sealed the mouthparts with superglue, (2) removed the abdomen and left the propodeal foramen open, the propodeal foramen is the opening that serves as the passage for nerves, trachea, alimentary tract, some muscles and hemolymph between the meso- and metasoma, (3) removed the abdomen and sealed the propodeal foramen with superglue.

Maimed males without sealed propodeal foramena were unable to nod their heads or extrude their mouthparts but they gained back the ability to perform these behavior if the sealing of their propodeal foramen took place shortly after the “amputation” of the metasoma. Normal males with sealed mouthparts (nodding is possible but mouthpart extrusion and mandible movement not) and maimed males with unsealed propodeal foramen were not able to provoke receptivity in females, whereas control (untouched) males and males with sealed propodeal foramen were able to increase the “sexual desire” of female wasps.

The results of these quite superglue intensive experiences clearly shows that the male Nasonia vitripennis specimen producing a pheromone somewhere around the mouthparts and that the head nodding and mouthparts extrusion are important factors for the aphrodisiac effect.

The authors hypothesized that

- There has to be an intricate system operating with pressure change of the hemolymph required for head nodding and mouthparts protrusion and thus gland release.

and that

- The mandibular gland might be the source of the enigmatic aphrodisiac.

And that’s it. Two papers published in 1980 and 1981 and not a single follow up! How can it be? The observations of van den Assem et al. certainly raised plenty of questions to be answered, but somehow this subject on Nasonia aphrodisiac has been sunk into oblivion. Were the hypotheses of van den Assem et al., right? What are the compounds of this pheromone? Is it really produced by the mandibular gland? Where is it located then and how is it released?

By the way, does Nasonia vitripennis even have a mandibular gland?

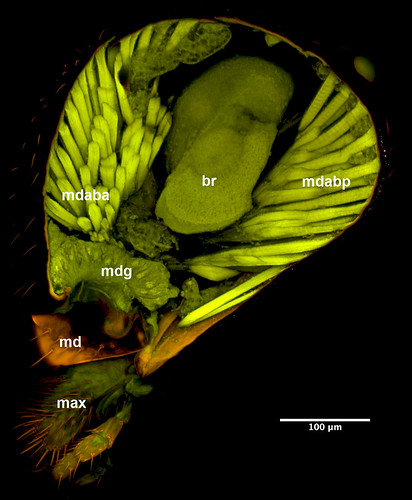

Driven by the latter, morphology-related questions we acquired some live individuals from our colleague, Jack Werren. We were able to answer the last question pretty quickly and confirmed the presence of a rather large mandibular gland with Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy.

What about the remaining questions? Here at Penn State we do have almost endless opportunity to start again with the Nasonia aphrodisiac questions. With the new Serial Block Face SEM we should be able to gather 3D data and reconstruct the mandibular base and the head of these tiny wasp and provide some insights about the mandibular gland system. And, with a bit more effort, we could utilize recent advances in proteomics and perform some behavior experiments and eventually confirm/reject van den Assem’s hypotheses and finally open the door to further researches on this very exciting morpho-ethological system.

Leave a Reply