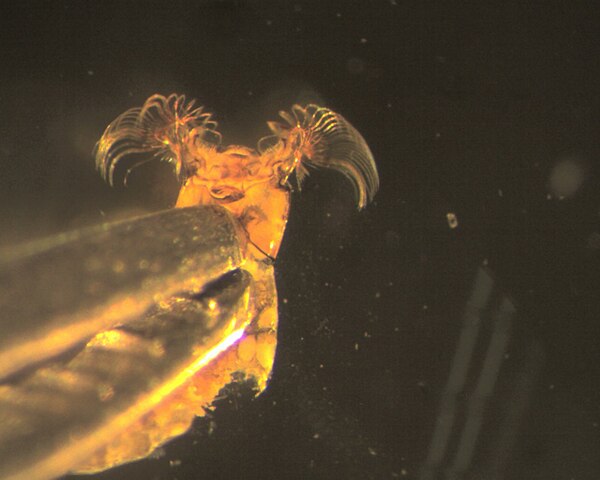

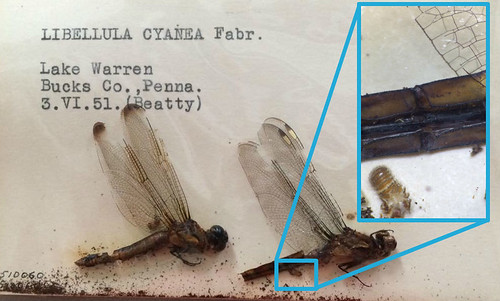

Curators of natural history collections must keep a watchful eye out for dermestid beetle larvae, pupae, exuviae, and damage during normal maintenance. You may have heard of dermestid beetles before, as they are often utilized in the cleaning of bones for museums, but in entomological collections, this same ability to eat dead material is problematic. At the Frost, our protocol is to make note of when exuviae are seen, and then to freeze treat the specimens on which the exuviae were found for at least a week in a -30°F freezer. I became curious about the phenomenon of a beetle that will eat an insect collection, and decided to look further into the beetle and how other collections around the country handle this aspect of keeping an insect collection safe.

There are a few types of dermestids which commonly attack insect collections, including those in the genera Anthrenus, Attagenus, and Reesa (Pinninger and Harmon, 1999). Dermestids will likely make their way into a collection as eggs on a specimen which has been incorporated. Signs of dermestid damage include holes in pinned specimen, a black “dust” under specimen (the frass of the beetles), and empty exuviae on or around a specimen. Other known pests of insect collections include beetles in the genus Ptinus (spider beetles), Psocoptera (booklice)1 and even cockroaches, as has been witnessed previously at the Frost and has even inspired some wonderful artwork!

Like the Frost, the American Museum of Natural History monitors their collection for damage, freezes boxes where damage is seen, and does not use fumigants2. The first step to keeping collections dermestid free includes a preventative step of making sure that specimens are stored in an airtight container3, and any new additions to the collection be monitored and treated before being added. Virginia Tech uses a system called “McGinleying” for this process when adding a lot of new specimens, which includes rating boxes on a scale of 1-10 to determine the amount of curation which will need to take place. To protect specimens from pests, the USDA recommends a few fumigants, including paradichlorobenzene (PDB) and naphthalene, although they warn of dangers to humans and note “that most major collections are now moving away from the use of solid fumigants because of health concerns and in some jurisdictions, it is now against regulations to use some fumigants.”3 Although there is not one standard across the board for preventing dermestid infestation in collections, it seems to be that everyone is moving away from fumigants and towards preventative curation through monitoring and keeping a clean environment.

.jpg)

On a final note, I wanted to compile some of the different recommendations for freeze treating specimens from several different places:

| Entomological Collection | Freeze Treating Recommendation |

| Frost Entomological Museum | 7 days, -30°F |

| USDA Agricultural Research Service3 | 2–5 days, -20ºC to -25ºC (-4 to -13°F) |

| American Museum of Natural History2 | 2 days, no specific temperature found |

| Virginia Tech Insect Collection4 | 72 hours, no specific temperature |

Do you have any different recommendations than these which I found?

Have a great week!

Pinniger, D. B. & Harmon, J. D. (1999). Pest management, prevention and control. In: Carter, & Walker, A. (eds). (1999). Chapter 8: Care and Conservation of Natural History Collections. Oxford: Butterwoth Heinemann, pp. 152 – 176. http://www.natsca.org/care-and-conservation

1 http://bughunter.tamu.edu/preservation/preservationconsider/

2 http://www.amnh.org/learn/biodiversity_counts/read_select/hs/maintain.htm

3 http://www.ars.usda.gov/News/docs.htm?docid=10141&page=11

4 http://collection.ento.vt.edu/?p=120

Updated 15 March 2016 to fix typos