By Jacqueline Reid-Walsh

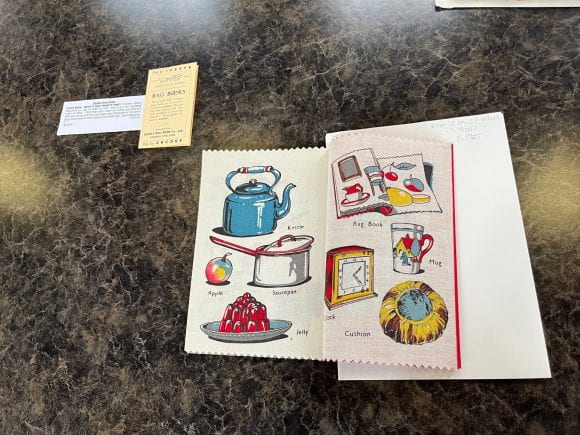

Tony Sarg’s Magic Movie Book in collaboration with Emery I. Gondor; ten tales that will never die rewritten in modern style by Hazel Seaman and Christina De La Motte …; eighteen poems and jingles by poets who will live forever, 1943.

I have been fortunate to work with two copies of this unusual interactive book, first the Penn State Special Collections Library and now the FTB (Fondazione Tancredi di Barolo). They appear to be the same edition and both are complete. The one at Penn State has the paper cover while the one at FTB has tabs that are easier to move. The book contains several kinds of materials to create animation and an illusion of projectile movement. At base are line drawings in two colors blue and red –they make no sense when viewed without the prosthetics, for example, there are extra legs of the wrong color on a character. Using fused pages most effectively there are dials or volvelles protruding from the sides of the pages and cut-out windows for a viewer to look through. The metal rivets attaching the volvelles are visible and touchable in the center of the pages. An interactor needs to move the protruding part of the dial to create movement.

Initially the movement makes no sense, but the “magic glasses” change everything. The plastic glasses have blue and red lenses with movable tabs at the sides. An interactor achieves the intended effects by moving the tabs up and down to change the colors. Since the drawings are red and blue switching the colored lenses makes the figures seem to move.

The glasses are separate from the book but attached to the front matter. They are packaged as a prop but are not an “extra”: rather their function is essential to the book’s movable design. In many cases the glasses get lost or are damaged and so are too fragile to play with. It was only when I was able to interact easily with the glasses did I understand the complexity and integrity of the book. Moreover, this book is one of the few movable books I have seen that invites the engagement of more than one person, for two sets of glasses are thoughtfully provided. The visual context is of children, female and male at a movie theatre. This context is depicted on the hard cover and repeated on the paper cover.

How does this book work? I am not used to playing with “magic glasses” and my experience with a similar kind of interactivity is from playing with a later version of the view master toy years ago (note 1). This ingenious book works in terms of multiple interactivities of sight and touch to create both pre-cinema animation of the images and the illusion of projectile movement which in also evokes the tactile. I think of an observations Walter Benjamin made about Dadist film in his “The work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction” (1936). He states,

“[Dadaist art] hit the spectator like a bullet, it happened to him, thus acquiring a tactile quality. It promoted a demand for the film, the distracting element of which is also primarily tactile, being based on changes of place and focus which periodically assail the spectator” (note 2).

I think the magic glasses and the moveable dials create a similar projectile effect since the images seem to move out of the page toward the interactor. Sarge creates the effect in a simple way when illustrating the nursery rhymes since an interactor simply puts on the glasses and moves the tabs. The effect is more complex and the interactor has more agency when moving the disc while wearing the glasses to animate the retold tales.

This scan shows Cinderella on the right side, while on the front end paper there are instructions on how to use the glasses. (Volvelle not visible)

As indicated by the long title, the book is a kind of anthology or omnibus volume with a co-author discussed below and other contributers. The fairy or folk tales are retellings written by Hazel Seaman and Christina De La Motte. They are short, jaunty, cartoon-like and presume a knowledgeable reader. Both the beleaguered heroes and heroines are equally savvy and take advantage of the situation and stereotypical villains. For example, with the first disc we encounter “Cinderella” and on one side “The Three Little pigs” on the other. The endings give agency to the protagonists: both Cinderella and the prince decide to marry at once “since neither favored long engagements.” With “The three little pigs” the oldest brother, after scalding the wolf, performs a cesarean section on the wolf as in “Red Riding Hood” and rescues his brothers. They learn from their mistakes and make brick houses like him.

When an interactor engages with the disc, we rotate through the key episodes in the story in accordance with the text. If we wish, we could rotate it contrarywise or focus on a couple of sequences. The physical artifact of the two-sided discs also creates intriguing juxtapositions between the tales.

The book effectively creates a “toy-like” semi-immersive experience where the interactor is the reader-narrator-viewer and the film projectionist who controls the speed and direction of the movement.

This image shows the three little pigs design format on the left side, while on the right is a simpler form of animation with no volvelle or tabs illustrating two well -known nursery rhymes. (volvelle visible on left hand side)

There is one lingering question: Is this book just a one-off trick or an experiment? Or both? It is a notable achievement combining animation and the illusion of three-dimensional perspective achieved by the interactor by touch and sight. Sarg was an expert in creating actual movements and the illusion of movement. He worked with material objects like puppets on different scales ranging from the toy theatre to balloon puppets, and created ingenious movable books that combine different textures, materials, and invite active exploration by an interactor. He was also a pioneer in film animation, creating “Adam Raises Cain” (1920) and “The First Circus” (1921), a silhouette film (Tamara Hunt, p. 32-25).

Unfortunately, this book was published posthumously after Sarg’s sudden death in 1942. It is a collaborative project with Emerich (Emery) I. Gondor (1896-1977), a psychotherapist and artist who immigrated to the United States in 1935 and became a citizen in 1941 (note 3). I would like to know what Gondor’s role was in the invention and their plans. Another question I have is Sarg’s choice of line illustrations for the animation, not more complex images. In this way I wonder if he is hearkening back to the 19th century in the early day of pre-cinema of which he was knowledgeable. I include a link to the Magic Media Museum online and the 1830 experiments with dancing figures to support this idea (note 4).

Notes

- Viewmaster toy first introduced in 1939 at the world’s fair and intended for adults; see https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/nmah_1129885.

- Benjamin goes on to contrast film with a painting: “Let us compare the screen on which a film unfolds with the canvas of a painting. The painting invites the spectator to contemplation; before it the spectator can abandon himself to his associations. Before the movie frame he cannot do so. No sooner has his eye grasped a scene than it is already changed. It cannot be arrested … The spectator’s process of association in view of these images is indeed interrupted by their constant, sudden change. This constitutes the shock effect of the film …” (XIV; 238; cited in Reid-Walsh 2007).

- See the finding aid for the Emery I. Gondor collection at the Center for Jewish History. The content note gives the following information: “During World War II, he worked for the War Department and was Chief of the Technical Operation Unit in the Overseas Service for France and Germany for two years. This unit performed classified work in counter-espionage. Gondor was also an instructor at the training schools in New York, France and Germany, where he taught about the psychological problems of counter-espionage as well as wrote several classified manuals on the subject.”

- Magical media museum channel on YouTube

References

Benjamin, Walter. Illuminations. Ed. by Hannah Arendt. New York: Schocken, 1969.

Hunt, Tamara. Tony Sarg Puppeteer in America, 1915-1942. Garden City BC: Charlemagne Press, 2018.

Reid-Walsh, Jacqueline. “Everything in the Picture Book Was Alive”: Hans Christian Andersen’s Strategy of Textual Animation in His Fairy Tales and the Interactive Child Reader.” In Johan de Mylius et al. (Eds.), Hans Christian Andersen: Between Children’s Literature and Adult Literature (pp. 275-289). Odense: University of Southern Denmark Press, 2007.