So far in this discussion of issues concerning the Native American tribal communities across the United States, I have covered the exponentially high rates of poverty and the continuous fight against oil pipeline initiatives. In this entry, I will be delving into tribal education, specifically how the U.S has denied tribes the right to govern their citizens’ education. This has resulted in poor quality education within the federally funded institutions. Part of the Native American Rights Fund’s (NARF) work focuses on restoring this governance. In the 2000s, this organization created the Tribal Education Departments National Assembly (TEDNA). Today, they work with TEDNA to strengthen tribal governance in education, which includes working with Indian Education for All and other tribal educational facilities.

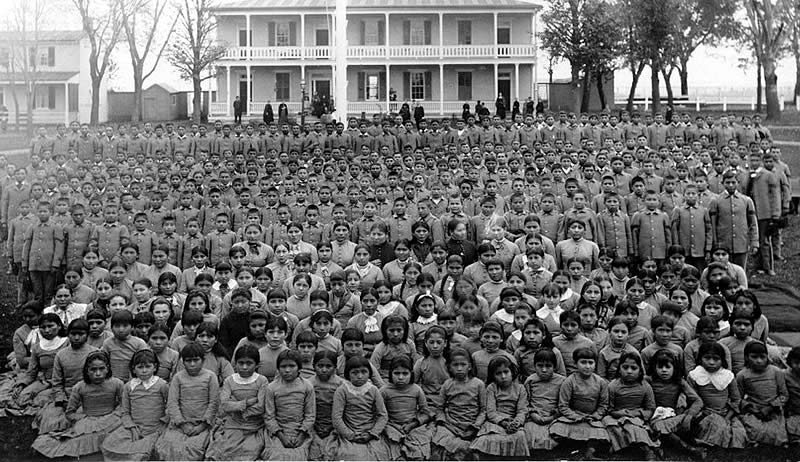

Before I elaborate on current events concerning the education of Native Americans, it is important to know our nation’s dark history of attempting to “Americanize” indigenous children. In 1860, the U.S government created boarding schools for the assimilation of Native American children into society. The children were forcibly taken from their families, and those in charge of the schools forced them to cut their long hair and forbid them from speaking in their native tongue, wearing their cultural garb, and performing their religious practices. These institutions harbored an abusive environment that often imposed manual labor while reinforcing the idea that their indigenous culture and languages were inferior to American culture and the English language. These schools did not officially end until the last one closed in 1978.

As I had mentioned in my first Civic Issue Blog entry, my dad taught Geography and American History at the Pierre Indian Learning Center from the fall of 2000 to the spring of 2002, with the exception of the spring of 2001. This school still runs today, for it is a boarding school for grades 1st-8th with kids from 15 different reservations in North Dakota, South Dakota, and Nebraska. The education of its students is in accordance with the State of South Dakota Department of Education (SDDOE) content standards, which align to the required Bureau of Indian Education (BIE) content standards. The BIE’s mission is “to provide quality education opportunities from early childhood through life in accordance with a tribe’s needs for cultural and economic well-being, in keeping with the vast diversity of Indian tribes and Alaska Native villages as distinct cultural and governmental entities. Further, the BIE is to manifest consideration of the whole person by considering the individual’s spiritual, mental, physical, and cultural aspects within his or her family and tribal or village context.”

Currently, there are 183 BIE-funded elementary and secondary schools on 64 reservations in 23 states, serving approximately 40,000 Indian students. Of these, 55 are BIE-operated and 128 are tribally controlled under the organization’s contracts or grants. These statistics are important to note, however the schools are struggling on multiple fronts including curriculum, lack of skilled teachers, under funding, lack of technology, and issues with the physical structure of the buildings.

In regard to issues with the curriculum, a Government Accountability Office report found that schools associated with the BIE were so mismanaged that it had given them permission to use assessments that failed to meet federal requirements. Additionally, many schools have insufficient curriculum to properly teach Native language and culture, which is related to the fact that the school is run by the federal government rather than the tribe itself.

Like many schools that are located in rural areas of America, BIE schools are underfunded and find it difficult to attract (and keep) qualified educators and administrators, even within their own tribe. The lack of funding for schools that are operated by tribal school boards stems from their reliance on funds from the federal government, which already does not have adequate funds for public education in the majority of states. The school district that I graduated from in southern Pennsylvania fits into this category of an underfunded public school district, so I cannot imagine the quality of indigenous schools that are in much worse shape than I was.

In terms of technology within these institutions, 60% of Native schools fall behind 21st century advancements, often lacking the bandwidth or computer access to support online learning. While I gathered this statistic from The Red Road organization’s website, I would be interested in researching more about how this particular drawback was magnified during the pandemic as it relied on online learning to continue the educational process.

And finally, the structural issues within Native American schools are abundant, for many of them are in extreme states of disrepair, which includes leaking roofs and walls, mold, and the presence of asbestos. These traits existed within my middle school, so I know first hand how much of a hinderance on education it can be when a class has to evacuate a classroom due to harmful amounts of mold.

The Red Road organization also included other startling statistics regarding the current state of Native students in comparison to students of other major ethnic groups in America:

- “In one study of fourth graders, BIE students on average scored 22 percent lower for reading and 14 points lower for math than Native students attending public schools.”

- “Only 70% of the Native students who start kindergarten will graduate from high school, compared to a national average of 82 percent, according to NCES. Those attending BIE schools have an even lower graduation rate of 53%.”

- “Only 17% of Native students attend college, as opposed to the national average of 60%.”

- “While 28% of the general population holds a college degree, only 13% of Native Americans have a college degree.”

I am deeply saddened to learn about the severely negative impact that a lack of funding and resources in addition to geographic location can have on the quality of education for indigenous children across the country. My high school did not teach me nearly enough about Native American culture and the unfortunate history between their people and the colonists, but it is our job to increase awareness of the topic so that we can close the gap between tribal graduation rates and those of other ethnic groups.

Sources:

https://narf.org/category/tribal-education/

https://www.bie.edu/topic-page/bureau-indian-education

Great post! I really liked your use of images throughout, as well as statistics and research. Keep up the great work 🙂