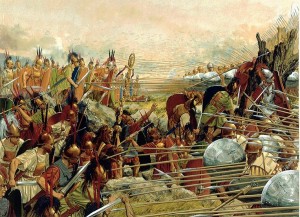

The Battle of Cynoscephalae, 197 BC, settled once and for all the age-old dispute of phalanx versus legionary warfare. Roman consul Titus Quinctius Flamininus entered Macedon with his two Senate-provided legions to confront and dethrone King Philip V in the Second Macedonian War.

As the Roman and Macedonian armies neared each other, skirmishes broke out between scouts near the town of Pherae. Neither commander wanted battle on that particular ground and poor weather minimized visibility, so they marched parallel to each other toward the town of Scotussa in hopes of better fighting ground and food, the armies separated by the Cynoscephalae hills.

Both commanders sent scouts over the hills to find the enemy, and were equally surprised to learn that the enemy lay right over the Cynoscephalae. The Macedonian scouts slowly overpowered the Romans, who requested aid from Flamininus. The Roman sent reinforcements, and as the Roman cavalry and light infantry repulsed the surging Macedonians, the skirmish moved from level ground to the summits of the Cynoscephalae. Philip responded in kind, and soon the skirmish grew to be a pitched cavalry and light infantry battle on top of the Cynoscephalae. The Roman light troops, now at a disadvantage, performed a fighting retreat back down the hills toward Flamininus and the main army. Philip, thinking his victory over the screening forces of the Romans more significant than it was, collected his encamped army and marched his phalanx to the summits of the Cynoscephalae.

Opposing Forces

Philip brought to the fight 16,000 phalanx pikemen, levied from all ages across his entire kingdom; perpetual war created a drought of man power, and the Macedonian king found it necessary to summon old men and young boys to arms against the Romans. 4000 peltasts supported this army, half of these Macedonian and the other half from neighboring kingdoms and tribes. The Macedonian army also contained 1500 mercenaries and a cavalry force 2000 strong.

Flamininus commanded two full legions, including supporting light infantry and cavalry. The Roman general also procured significant support from local allies; the Aetolians provided 600 infantry and 400 cavalry, and other localities sent 3000 soldiers, mostly skirmishers, to fight alongside the Romans. Flamininus also commanded elephants, brought from Numidia.

Flamininus formed his heavy infantry up for battle at the base of the Cynoscephalae, as Philip occupied the high ground with the first half of his phalanx troops to reach the hills. The Macedonian screening force was still locked in combat against the retreating Romans. On the opposite side of the Cynoscephalae were the rest of Philip’s phalanx pikemen, marching to take their place on the Macedonian left. Flamininus positioned his elephants on the right wing; the phalanx troops to be opposite these elephants had not yet taken up positions on Philip’s battle line.

The spaced organization of the Roman maniple allowed the retreating screening force to escape the Macedonians, who fled in turn from the sight of the Roman heavy infantry. Flamininus thus advanced through the retreating light forces without losing stride; he commanded from his left legion, and held his right legion and elephants in reserve for the time being. Philip ordered his right phalanx charge down into the Roman left; the Macedonians held the high ground and initially pushed the Romans back down the Cynoscephalae, albeit at a slow pace.

As the Roman line slowly fell back down the slope, it nevertheless held the phalanx in check; meanwhile, Flamininus ordered his right legion up the hill and charged his elephants into the still unformed Macedonian left. Unable to quickly change from the march oriented column formation to a line formation, the Macedonian left turned and ran rather than face the approaching slaughter. The Roman right pursued, but an unnamed tribune wheeled twenty maniples around and descended the slopes into the Macedonian right’s rear. If the counts of Polybius and Livy are to be believed, twenty maniples would account for about 2500 Roman infantry, split between hastati, principes, and triarii; this amounts to more than half a legion.

As the Roman line slowly fell back down the slope, it nevertheless held the phalanx in check; meanwhile, Flamininus ordered his right legion up the hill and charged his elephants into the still unformed Macedonian left. Unable to quickly change from the march oriented column formation to a line formation, the Macedonian left turned and ran rather than face the approaching slaughter. The Roman right pursued, but an unnamed tribune wheeled twenty maniples around and descended the slopes into the Macedonian right’s rear. If the counts of Polybius and Livy are to be believed, twenty maniples would account for about 2500 Roman infantry, split between hastati, principes, and triarii; this amounts to more than half a legion.

Now pressed from behind by this massive force and unable to face their massive pikes to the rear, the Macedonian right broke and fled. Philip had pulled back up to the summit for a better look at the battle; upon seeing the collapse of his right and the rout of his left, Philip fled the field. Flamininus claimed victory in an uphill battle against the previously invincible Macedonian phalanx. Polybius puts the Roman dead at 700, while of the Macedonians 8000 perished and 5000 were captured. Livy agrees with these estimates, dismissing higher claims by his contemporaries as exceedingly dramatic.

Such minimal losses on the side of the Romans seems hard to believe, yet had the casualties been more equally proportional between Rome and Macedon, surely the left Roman legion would have been brought “down to the triarii.” The absence of any mention of such desperation, and indeed the absence of even the hastati being eliminated, makes the dramatic ratio of Roman to Macedonian dead easier to imagine. Furthermore, the Macedonian phalanxes were unable to retreat from the Roman surround, and upon the surrender of the surrounded Macedonians, both Polybius and Livy claim that the Romans did not recognize the signal as the concession it was, and thus fell into the Macedonians with renewed vigor. Therefore, many of the Macedonians may have been slaughtered without resistance after the actual battle.

Such minimal losses on the side of the Romans seems hard to believe, yet had the casualties been more equally proportional between Rome and Macedon, surely the left Roman legion would have been brought “down to the triarii.” The absence of any mention of such desperation, and indeed the absence of even the hastati being eliminated, makes the dramatic ratio of Roman to Macedonian dead easier to imagine. Furthermore, the Macedonian phalanxes were unable to retreat from the Roman surround, and upon the surrender of the surrounded Macedonians, both Polybius and Livy claim that the Romans did not recognize the signal as the concession it was, and thus fell into the Macedonians with renewed vigor. Therefore, many of the Macedonians may have been slaughtered without resistance after the actual battle.

Significance

Polybius devotes special attention to the significance of the Battle of Cynoscephalae, as it dramatically revealed the superiority of the Roman maniple and the shortcomings of the Macedonian phalanx.

The Macedonian phalanx was unstoppable in a frontal charge; as Polybius puts it, “That when the phalanx has its characteristic virtue and strength nothing can sustain its frontal attack or withstand the charge can easily be understood for many reasons.” Polybius then points to the phalanx’s characteristics: a tightly packed phalanx offers five lowered pikes every three feet. Pikes from the sixth rank back are held in the air at an angle to protect the phalanx from missiles, thus making the phalanx virtually invulnerable to the front and from above.

The Macedonian phalanx was unstoppable in a frontal charge; as Polybius puts it, “That when the phalanx has its characteristic virtue and strength nothing can sustain its frontal attack or withstand the charge can easily be understood for many reasons.” Polybius then points to the phalanx’s characteristics: a tightly packed phalanx offers five lowered pikes every three feet. Pikes from the sixth rank back are held in the air at an angle to protect the phalanx from missiles, thus making the phalanx virtually invulnerable to the front and from above.

Roman maniples fought in a considerably more loose formation; every one Roman soldier faced two Macedonian pikemen, or ten pikes. Approaching the phalanx from the front would thus be damn near impossible for a Roman infantryman. However, Roman soldiers were better equipped and trained for one-on-one close quarters combat, armed as they were with the gladius and scutum. Hiding behind his scutum, the Roman soldier could cut and stab as required with his sword; as so ironically demonstrated at Cannae, the Roman infantryman could easily turn to face any threat from the flanks or rear.

The overall flexibility of the Roman maniple proved superior to the Macedonian phalanx as Flamininus could form up his heavy infantry, have his retreating screen fall between the ranks, hold back half his army, engage with the other half, and wheel his reserve legion around into an organized attack on the Macedonian rear without any real strain on his command. The Roman chain of command proved independent and capable of making intelligent calls mid-battle, as demonstrated by the unnamed Roman tribune who brought Flamininus his decisive victory. Roman infantry could change formation and engage enemies on new fronts without much trouble, while the Macedonian pikemen could only form up half their line before the battle began, despite the Romans being required to charge up the steep hills of Cynoscephalae. The Macedonian scouts and cavalry had no way of falling through the phalanx as the Romans had fallen through the maniple, and were thus required to fall in at the far right of Philip’s line, from which position they could not check the advance of the Roman right.

As previously stated, the success of the Roman legion over the Macedonian phalanx at Cynoscephalae proved dramatic, yet the results are undeniable. The Roman legion’s flexibility allowed heavy infantry to combat any enemy on any front, and because of this ability to adapt and overcome, Flamininus destroyed what remained of Philip’s power and finished Roman conquest of Greece.

[Polybius 18.19-27]

[Livy 33.1-11]