By: Chandler Penn

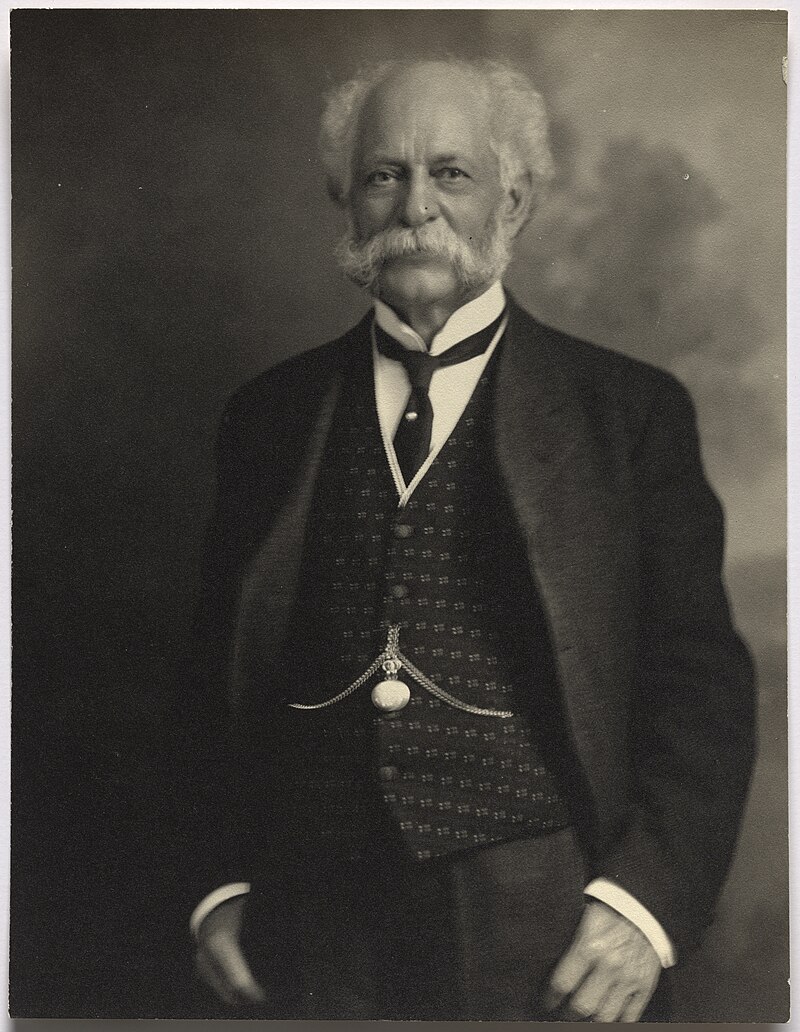

Unlike most countries, it is not easy to identify quintessential American food items. For example, some people think of mashed potatoes, but mashed potatoes were first invented and introduced in Great Britain. Others might think of Barbecue, but Barbecue first originated in the Caribbean. I might be biased, but one food item that comes to mind that was both created and popularized in the United States of America is Ketchup. While Henry Heinz did not invent Ketchup, he is rightfully credited with making it a staple in the American diet, and a condiment loved around the world.

early life

Born in Pittsburgh, PA in 1844, Henry was the oldest of eight children. Both of his parents immigrated to the U.S. from Germany and met in Pittsburgh. Henry’s father worked for brickmakers for a few years before deciding to start his own brickyard in 1850. Inspired by his father’s entrepreneurial spirit, Henry began selling the surplus vegetables from his family’s garden at the age of nine.

Born in Pittsburgh, PA in 1844, Henry was the oldest of eight children. Both of his parents immigrated to the U.S. from Germany and met in Pittsburgh. Henry’s father worked for brickmakers for a few years before deciding to start his own brickyard in 1850. Inspired by his father’s entrepreneurial spirit, Henry began selling the surplus vegetables from his family’s garden at the age of nine.

By the age of twelve, Henry had his own three acres to grow produce and he also upgraded to a horse and cart for his deliveries. At fifteen, he started making bottled horseradish to prevent people from making their own through a labor intensive and undesirable process. His genius marketing skills quickly showed as he decided to place the horseradish in expensive glass bottles. He believed that his customers would be assured of the horseradish’s purity and quality if they received it in a nice glass bottle. He was correct.

bankruptcy

At twenty-four, Henry entered into business with a wealthy friend. The company was called Heinz, Noble, & Company. In addition to horseradish, the company sold vinegar, mustard, pickles, sauerkraut, fruit preserves, catsup (early form of ketchup), and other items. Henry constantly experimented with seeds and produce to introduce new items to the company’s offerings.

At twenty-four, Henry entered into business with a wealthy friend. The company was called Heinz, Noble, & Company. In addition to horseradish, the company sold vinegar, mustard, pickles, sauerkraut, fruit preserves, catsup (early form of ketchup), and other items. Henry constantly experimented with seeds and produce to introduce new items to the company’s offerings.

The company grew for five years and proved to be very successful. The anchor branding was introduced in these years, which is still placed on every bottle of Heinz to this day. Having a recognizable brand was unique at this time because most food companies sold their products out of undifferentiated barrels. Once again, Henry’s marketing genius set his products apart. However, the Panic of 1873 hit Pittsburgh hard, eventually causing the company to go bankrupt by 1875. This resulted in a very low point in Henry’s life.

redemption

By 1876, Henry’s entrepreneurial spirit had revived and he started a new adventure, F & J Heinz Company, by pooling money from his wife and his cousins. Not only did he work hard to build this new company, but he also showed his honorable nature by paying off all the debts of his previous company even though he was under no legal obligation to do so. Henry was obsessed with offering the best product to his customers. He had a saying that the company operated from “soil to customer.” This meant that he wanted to use the freshest and best produce in his products, the safest and purest manufacturing processes, and to offer the finest and most affordable glass bottles for the food items to be presented in.

Henry’s emphasis on using fresh produce and natural food products was revolutionary during a time when many companies used saw dust and other unnatural items to stuff their processed food. Henry’s disgust with this practice in the food industry caused him to successfully lobby and assist Congress in passing the Pure Food and Drug Act. However, he was not entirely self-interested because the passage of this act created a major advantage for his company which had already been operating under the food purity guidelines of this law.

marketing genius

Henry’s entrepreneurial ability flowed most naturally from his extraordinary ability to market his products. One of his favorite marketing tactics was to set up booths at world fairs. At the 1893 Chicago Fair, the most well attended world fair in history, Henry was given a booth in the least visited part of the fair—the second story of the agriculture building. Henry did not let this discourage him, but he instead walked around the fair handing out free coupons to be redeemed at his booth. When the people turned in the coupons, they were given pickle pins with the Heinz logo on them. These pins became so popular that the second floor of the agriculture building had to be reinforced because of the thousands of visitors who gathered and waited in lines to visit Henry’s booth.

Henry found other unique ways to market his product. He had a fleet of trains that were decked out in the Heinz logo, and he even  designed some of his delivery wagons to look like his famous pickles. One of his largest marketing missions took place when he bought the Ocean Pier in Atlantic City, NJ. Here, Henry offered educational exhibits, art, music, and product sampling. It is estimated that the pier had over 15,000 people a day during peak season, and Heinz’s sales jumped 30% in the first year that it owned the pier. These are just a few of the many creative ideas that Henry Heinz employed in marketing a company that has a brand as ubiquitous as any other company in America to this day.

designed some of his delivery wagons to look like his famous pickles. One of his largest marketing missions took place when he bought the Ocean Pier in Atlantic City, NJ. Here, Henry offered educational exhibits, art, music, and product sampling. It is estimated that the pier had over 15,000 people a day during peak season, and Heinz’s sales jumped 30% in the first year that it owned the pier. These are just a few of the many creative ideas that Henry Heinz employed in marketing a company that has a brand as ubiquitous as any other company in America to this day.

conclusion

Although Henry Heinz ran a business over a century ago, we can still draw lessons from his time building the Heinz brand. Henry teaches us that selling and marketing one’s products is easiest when the product is of true quality and made from the best materials. He also teaches us that failure is part of being an entrepreneur, and that one does not need to give up if one of their venture’s fails. Lastly, he teaches us that creating a marketable and recognizable brand is important in creating a successful and long lasting business.

This post has been reproduced and updated with the author’s permission. It was originally authored on May 8, 2024 and can be found here.

Chandler Penn, at the time of this post, is a third-year law student at Penn State Dickinson Law and has a B.A. in History. He will be pursuing a career in transactional law upon graduation. He may be contacted directly at cbp5548@psu.edu.

Chandler Penn, at the time of this post, is a third-year law student at Penn State Dickinson Law and has a B.A. in History. He will be pursuing a career in transactional law upon graduation. He may be contacted directly at cbp5548@psu.edu.

Sources:

https://www.theellisschool.org/list-detail?pk=29093

https://hbswk.hbs.edu/item/henry-heinz-and-brand-creation-in-the-late-nineteenth-century#56

https://americanbusinesshistory.org/brand-man-the-hj-heinz-story/

https://www.thehenryford.org/collections-and-research/digital-collections/artifact/155246/

Although Cyrus patented the reaper in 1834, his focus was on an iron foundry the family bought. However, in 1837, an economic downturn resulted in the foundry failing. Cyrus decided to improve the reaper, and in 1844, he visited the Midwest and decided it was the future of grain growing. He built a factory in Chicago using $50,000 the mayor of Chicago contributed. His brother, Leander, managed the factory, while his brother, William, did marketing. In 1847, he sold 800 reapers compared to just two in 1841. Despite his success, Cyrus encountered a new challenge. His original patent expired in 1848, and he fought to have it renewed unsuccessfully, though fortunately, he had also patented his improvements on the original model. Cyrus was a regular patron of the Supreme Court, with many of his cases presiding before them. Typically, over allegations of patent infringement, but in his private life, he turned a dispute over an $8.70 excess luggage fee into a 23-year legal battle, where he won a rather pyrrhic victory.

Although Cyrus patented the reaper in 1834, his focus was on an iron foundry the family bought. However, in 1837, an economic downturn resulted in the foundry failing. Cyrus decided to improve the reaper, and in 1844, he visited the Midwest and decided it was the future of grain growing. He built a factory in Chicago using $50,000 the mayor of Chicago contributed. His brother, Leander, managed the factory, while his brother, William, did marketing. In 1847, he sold 800 reapers compared to just two in 1841. Despite his success, Cyrus encountered a new challenge. His original patent expired in 1848, and he fought to have it renewed unsuccessfully, though fortunately, he had also patented his improvements on the original model. Cyrus was a regular patron of the Supreme Court, with many of his cases presiding before them. Typically, over allegations of patent infringement, but in his private life, he turned a dispute over an $8.70 excess luggage fee into a 23-year legal battle, where he won a rather pyrrhic victory.

Benjamin Franklin is remembered for his political career, most notably for being one of the Founding Fathers of America, but did you know that he was also one of the most successful entrepreneurs of his time? His entrepreneurship spans across multiple industries, most prominent of which are printing and newspapers.

Benjamin Franklin is remembered for his political career, most notably for being one of the Founding Fathers of America, but did you know that he was also one of the most successful entrepreneurs of his time? His entrepreneurship spans across multiple industries, most prominent of which are printing and newspapers.

Franklin also ventured into the newspaper business. Franklin purchased the Pennsylvania Gazette in 1729. The newspaper was so popular that it has been dubbed the colonial equivalent of The New York Times. Franklin often contributed to the newspaper. He continued his witty, conversational writing style from his “Mrs. Silence Dogood” days, and devoted ample space to gossip and sensational crimes, all of which contributed to the newspaper’s popularity. It is of note that Franklin engaged in some less than exemplary business practices to purchase the Pennsylvania Gazette. Before purchasing it, he published some scathing reviews of the paper, which led to decreased circulation, and consequently, a lower purchase price.

Franklin also ventured into the newspaper business. Franklin purchased the Pennsylvania Gazette in 1729. The newspaper was so popular that it has been dubbed the colonial equivalent of The New York Times. Franklin often contributed to the newspaper. He continued his witty, conversational writing style from his “Mrs. Silence Dogood” days, and devoted ample space to gossip and sensational crimes, all of which contributed to the newspaper’s popularity. It is of note that Franklin engaged in some less than exemplary business practices to purchase the Pennsylvania Gazette. Before purchasing it, he published some scathing reviews of the paper, which led to decreased circulation, and consequently, a lower purchase price. By age 42, Franklin had made enough money to retire. Upon retirement, he devoted himself to scientific research, most famous of which is on electricity. His findings on electricity were of great value to future scientists. Among his various experiments, he flew a kite into a lightning storm to prove that it is a form of electricity.

By age 42, Franklin had made enough money to retire. Upon retirement, he devoted himself to scientific research, most famous of which is on electricity. His findings on electricity were of great value to future scientists. Among his various experiments, he flew a kite into a lightning storm to prove that it is a form of electricity.

Jamsetji Tata was one of India’s biggest and most famous industrialists. Born in 1839 in Navsari, Gujarat, Tata received a Western education, unlike his peers. Tata joined his father’s company upon graduation and in less than two decades, he formed his own company.

Jamsetji Tata was one of India’s biggest and most famous industrialists. Born in 1839 in Navsari, Gujarat, Tata received a Western education, unlike his peers. Tata joined his father’s company upon graduation and in less than two decades, he formed his own company. The Swadeshi Movement, which was the catalyst that led to the Freedom Movement, had not started yet. In the early 1990s, politically conscious Indians wanted to develop industries and resources in India by Indians. Tata followed this sentiment before its prominence. Near the end of Tata’s life, the movement picked up momentum. The momentum was so consequential that he named one of his mills Swadeshi.

The Swadeshi Movement, which was the catalyst that led to the Freedom Movement, had not started yet. In the early 1990s, politically conscious Indians wanted to develop industries and resources in India by Indians. Tata followed this sentiment before its prominence. Near the end of Tata’s life, the movement picked up momentum. The momentum was so consequential that he named one of his mills Swadeshi. One of the last things Tata did was inaugurate the Taj Mahal Hotel in Mumbai in 1903. At the time, it cost 11 million rupees (approximately $11 billion today). Today, it is one of the best hotels in India. He wanted to build it after being refused entry for being Indian. It was a one-of-a-kind luxury hotel with American fans, German elevators, English butlers, and Turkish baths. Tata died soon after in 1904.

One of the last things Tata did was inaugurate the Taj Mahal Hotel in Mumbai in 1903. At the time, it cost 11 million rupees (approximately $11 billion today). Today, it is one of the best hotels in India. He wanted to build it after being refused entry for being Indian. It was a one-of-a-kind luxury hotel with American fans, German elevators, English butlers, and Turkish baths. Tata died soon after in 1904. Tata fought for India’s economic freedom before the Freedom Movement started. He fought for goods to be made in India before the Swadeshi Movement started. He donated immensely to charities and funds to uplift Indians in access to education and health care. Jamsetji Tata remains an inspiration to Indians around the world.

Tata fought for India’s economic freedom before the Freedom Movement started. He fought for goods to be made in India before the Swadeshi Movement started. He donated immensely to charities and funds to uplift Indians in access to education and health care. Jamsetji Tata remains an inspiration to Indians around the world. Vinanti Pandya, at the time of this post, is a second-year law student at Penn State Dickinson Law. She is originally from India but is technically from Canada. She is a graduate of the University of Toronto. Vinanti is the current Vice President of the North American South Asian Law Students’ Association and a member of the Moot Court Team.

Vinanti Pandya, at the time of this post, is a second-year law student at Penn State Dickinson Law. She is originally from India but is technically from Canada. She is a graduate of the University of Toronto. Vinanti is the current Vice President of the North American South Asian Law Students’ Association and a member of the Moot Court Team. “You’re not fully dressed unless you wear a hat.” Mae Reeves was an entrepreneur, activist, artist, and pioneer of fashion. Reeves was one of the first women of color to own her own business in the city of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. She is most well-known for her intricate custom-made hats. Over the course of her stores’ 56 years of operation, her creations became symbols of dignity and womanhood to other African American women in Philadelphia. Undoubtedly, Reeves is a symbol of hard-work, vision, and dedication.

“You’re not fully dressed unless you wear a hat.” Mae Reeves was an entrepreneur, activist, artist, and pioneer of fashion. Reeves was one of the first women of color to own her own business in the city of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. She is most well-known for her intricate custom-made hats. Over the course of her stores’ 56 years of operation, her creations became symbols of dignity and womanhood to other African American women in Philadelphia. Undoubtedly, Reeves is a symbol of hard-work, vision, and dedication.  Mae Reeves was born Lula Mae Grant in 1912. She was born in Georgia and spent most of her childhood there. When Reeves was 16, she received her teaching certification and began to teach in Lyons, Georgia. In addition to teaching, she also worked as a writer for the Savannah Tribune newspaper, writing “about social, school, and church affairs.” During her summers off, Reeves traveled to stay with family in Chicago. While there, she attended the Chicago School of Millinery, where she learned how to make hats.

Mae Reeves was born Lula Mae Grant in 1912. She was born in Georgia and spent most of her childhood there. When Reeves was 16, she received her teaching certification and began to teach in Lyons, Georgia. In addition to teaching, she also worked as a writer for the Savannah Tribune newspaper, writing “about social, school, and church affairs.” During her summers off, Reeves traveled to stay with family in Chicago. While there, she attended the Chicago School of Millinery, where she learned how to make hats.

The store was not just a place to purchase a hat, but it was a center for women’s empowerment. Women, particularly African American women, had a place to go where they were treated with dignity and compassion. Tiffany Gill, an author who has written on African American women’s activism within the beauty industry, said the following regarding hat stores at the time: “For black women who grew up in the Jim Crow era…hats were a way for them to take ownership over their style, a way for them to assert that they mattered.” This was one of the few places at the time where all women could be treated equally. Reeves’ artistry gave women an outlet to express themselves through fashion and the opportunity to find community.

The store was not just a place to purchase a hat, but it was a center for women’s empowerment. Women, particularly African American women, had a place to go where they were treated with dignity and compassion. Tiffany Gill, an author who has written on African American women’s activism within the beauty industry, said the following regarding hat stores at the time: “For black women who grew up in the Jim Crow era…hats were a way for them to take ownership over their style, a way for them to assert that they mattered.” This was one of the few places at the time where all women could be treated equally. Reeves’ artistry gave women an outlet to express themselves through fashion and the opportunity to find community. Mae’s Millinery Shop was open for more than 50 years. In fact, Reeves asked that the store remain open even after she moved to a retirement home in case she wanted to come back to make more hats. The contents of her store were eventually donated to the Smithsonian. Her hats are now in a permanent exhibit at the National Museum of African American History and Culture. Reeves lived a long life of 104 years and eventually passed away in 2016. While she was never able to visit her exhibit due to her passing, she participated in an interview with the Smithsonian about the exhibit prior to its opening. During that interview she stated that making hats “

Mae’s Millinery Shop was open for more than 50 years. In fact, Reeves asked that the store remain open even after she moved to a retirement home in case she wanted to come back to make more hats. The contents of her store were eventually donated to the Smithsonian. Her hats are now in a permanent exhibit at the National Museum of African American History and Culture. Reeves lived a long life of 104 years and eventually passed away in 2016. While she was never able to visit her exhibit due to her passing, she participated in an interview with the Smithsonian about the exhibit prior to its opening. During that interview she stated that making hats “ Abbie Britton, at the time of this post, is a third-year law student at Penn State Dickinson Law. She is a former graduate of York College of Pennsylvania, with a degree in Business Administration and a focus on Human Resource Management. She plans to pursue a career in Employment Law after obtaining her law degree.

Abbie Britton, at the time of this post, is a third-year law student at Penn State Dickinson Law. She is a former graduate of York College of Pennsylvania, with a degree in Business Administration and a focus on Human Resource Management. She plans to pursue a career in Employment Law after obtaining her law degree. There are very few pop culture interests shared among people all over the world and of all ages. Whether you live in Hong Kong or America, are two years-old or ninety-two years old, you would be hard-pressed to find someone who hasn’t heard of Disney. If you ask five different people the first thing they think of when they hear the word “Disney,” you’d likely hear five different answers: movies, amusement parks, streaming services, Mickey Mouse, or maybe even the Happiest Place on Earth. However, none of these experiences would have been possible without the person behind the magic—Walter Elias Disney.

There are very few pop culture interests shared among people all over the world and of all ages. Whether you live in Hong Kong or America, are two years-old or ninety-two years old, you would be hard-pressed to find someone who hasn’t heard of Disney. If you ask five different people the first thing they think of when they hear the word “Disney,” you’d likely hear five different answers: movies, amusement parks, streaming services, Mickey Mouse, or maybe even the Happiest Place on Earth. However, none of these experiences would have been possible without the person behind the magic—Walter Elias Disney. Having just lost his team of animators and first successful character, Disney continued to persist and created the iconic Mickey Mouse. After Mickey’s debut in a couple of silent cartoons, Disney decided to do something that hadn’t been done before. He created one of the first cartoons with synchronized sound, a short film titled Steamboat Willie. It was then that Mickey Mouse rose to stardom. Not only did Disney create Mickey Mouse, but he was the voice of the character until 1947.

Having just lost his team of animators and first successful character, Disney continued to persist and created the iconic Mickey Mouse. After Mickey’s debut in a couple of silent cartoons, Disney decided to do something that hadn’t been done before. He created one of the first cartoons with synchronized sound, a short film titled Steamboat Willie. It was then that Mickey Mouse rose to stardom. Not only did Disney create Mickey Mouse, but he was the voice of the character until 1947. Walt Disney didn’t limit himself to creating movies about flying elephants and singing birds. During World War II, the federal government retained Disney to create films that would educate the public about the war. One of those short films, The New Spirit, starred Donald Duck and encouraged people to pay their income taxes as a way to fund the war.

Walt Disney didn’t limit himself to creating movies about flying elephants and singing birds. During World War II, the federal government retained Disney to create films that would educate the public about the war. One of those short films, The New Spirit, starred Donald Duck and encouraged people to pay their income taxes as a way to fund the war. What started out as a man with a dream turned into a company worth $200.10 billion. The Walt Disney Company has become one of the most well-known and respected entertainment moguls in the 21st century. The Disney phenomenon is so prevalent in today’s culture that adult members of the fandom are widely referred to as “Disney Adults.” Next time you visit the Happiest Place on Earth, don’t forget to snap a photo by the statue of the men who started it all—Walt Disney and Mickey Mouse.

What started out as a man with a dream turned into a company worth $200.10 billion. The Walt Disney Company has become one of the most well-known and respected entertainment moguls in the 21st century. The Disney phenomenon is so prevalent in today’s culture that adult members of the fandom are widely referred to as “Disney Adults.” Next time you visit the Happiest Place on Earth, don’t forget to snap a photo by the statue of the men who started it all—Walt Disney and Mickey Mouse.

Maggie Lena Walker was born on July 15, 1864, in Richmond, Virginia, where she lived her entire life. She was born into poverty and practically born into hard work. At age 12, Walker was already instrumental in her mother’s laundry business that provided the only source of income for the family. Segregation and the inequities it produced marred Walker’s education. In 1883, she participated in a boycott with her graduating class to protest the inadequate academic facilities afforded people of color. The National Park Service suggests this school strike may have been the first one of the Civil Rights Movement, placing Walker at the forefront of this historic time. The boycott was only the beginning of Walker’s work. Despite her humble beginnings, she lived life with a higher purpose and is one of the most important Black businesswomen in history.

Maggie Lena Walker was born on July 15, 1864, in Richmond, Virginia, where she lived her entire life. She was born into poverty and practically born into hard work. At age 12, Walker was already instrumental in her mother’s laundry business that provided the only source of income for the family. Segregation and the inequities it produced marred Walker’s education. In 1883, she participated in a boycott with her graduating class to protest the inadequate academic facilities afforded people of color. The National Park Service suggests this school strike may have been the first one of the Civil Rights Movement, placing Walker at the forefront of this historic time. The boycott was only the beginning of Walker’s work. Despite her humble beginnings, she lived life with a higher purpose and is one of the most important Black businesswomen in history. Over the summer, my family and I traveled to Richmond, Virginia, where we had the pleasure of touring Walker’s home. The visit stands out in my mind as the best historical tour I have experienced. The National Park Service staff was extremely knowledgeable and introduced us to Walker’s life with the utmost reverence and respect. Unfortunately, due to COVID, only the first floor of the home was open to tours, yet no one in my party felt shortchanged. Instead, we felt grateful for the opportunity to learn about such a historic woman and stand in the spaces she once occupied. Maggie Lena Walker’s legacy left us inspired, and the tour left us with a t-shirt featuring an eloquent quote by Walker that reminds us of who she was:

Over the summer, my family and I traveled to Richmond, Virginia, where we had the pleasure of touring Walker’s home. The visit stands out in my mind as the best historical tour I have experienced. The National Park Service staff was extremely knowledgeable and introduced us to Walker’s life with the utmost reverence and respect. Unfortunately, due to COVID, only the first floor of the home was open to tours, yet no one in my party felt shortchanged. Instead, we felt grateful for the opportunity to learn about such a historic woman and stand in the spaces she once occupied. Maggie Lena Walker’s legacy left us inspired, and the tour left us with a t-shirt featuring an eloquent quote by Walker that reminds us of who she was: Savannah Wilt, at the time of this post, is a third-year law student at Penn State Dickinson Law. She achieved her MBA at Penn State Harrisburg and is a graduate of York College of Pennsylvania. Savannah is the current Treasurer of the Business Law Society and is pursuing a legal career in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

Savannah Wilt, at the time of this post, is a third-year law student at Penn State Dickinson Law. She achieved her MBA at Penn State Harrisburg and is a graduate of York College of Pennsylvania. Savannah is the current Treasurer of the Business Law Society and is pursuing a legal career in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Born on January 6, 1794, in Coatesville, Pennsylvania Rebecca Lukens would go on to become “America’s first female CEO of an industrial company” and matriarch of her family’s dynasty.

Born on January 6, 1794, in Coatesville, Pennsylvania Rebecca Lukens would go on to become “America’s first female CEO of an industrial company” and matriarch of her family’s dynasty. However, amidst the great success that Brandywine Iron Works and Nail Factory was experiencing it was not without some hardship along the way. In 1824, Lukens’s family died and left behind a convoluted will that led to an inheritance dispute. The mill was ultimately left in the Lukens’ hands since it was on the verge of bankruptcy. However, Charles passed away suddenly at the age of 39 in 1825 before we lived to see the order for the nation’s first ironclad steamship come to fruition.

However, amidst the great success that Brandywine Iron Works and Nail Factory was experiencing it was not without some hardship along the way. In 1824, Lukens’s family died and left behind a convoluted will that led to an inheritance dispute. The mill was ultimately left in the Lukens’ hands since it was on the verge of bankruptcy. However, Charles passed away suddenly at the age of 39 in 1825 before we lived to see the order for the nation’s first ironclad steamship come to fruition. Determined to keep her family business afloat, and provide for her children, Lukens kept forging ahead. The company completed the largest order the mill had received to date and the ironclad steamboat launched in November 1825. Without the support of her mother, who believed a woman should not be running businesses, she was able to capitalize on that success. Several of Charles’ business partners assisted her in working to save the mill. They loaned materials, worked on credit, and gave her time to pay back all the mill’s debts. She also partnered with her two sons-in-law to help run the operations. Even in 1837 when the nation faced a recession, Lukens was able to keep her whole workforce employed and working.

Determined to keep her family business afloat, and provide for her children, Lukens kept forging ahead. The company completed the largest order the mill had received to date and the ironclad steamboat launched in November 1825. Without the support of her mother, who believed a woman should not be running businesses, she was able to capitalize on that success. Several of Charles’ business partners assisted her in working to save the mill. They loaned materials, worked on credit, and gave her time to pay back all the mill’s debts. She also partnered with her two sons-in-law to help run the operations. Even in 1837 when the nation faced a recession, Lukens was able to keep her whole workforce employed and working. In the era of a man’s world in iron manufacturing, Lukens was able to make her mark on the industry. Under her direction, the company became a central player in the steel and iron business winning contracts for locomotives, sea-going vessels, steamboats, and more. In 1844, she was worth $60,000 (about $1.7 million today). Lukens died in 1854. The business continued in the family until 1998 when it was eventually bought by Bethlehem Steel.

In the era of a man’s world in iron manufacturing, Lukens was able to make her mark on the industry. Under her direction, the company became a central player in the steel and iron business winning contracts for locomotives, sea-going vessels, steamboats, and more. In 1844, she was worth $60,000 (about $1.7 million today). Lukens died in 1854. The business continued in the family until 1998 when it was eventually bought by Bethlehem Steel.

Rosa María Hinojosa was born in 1752 in what is now Tamaulipas, Mexico. Hinojosa was the sixth of nine children to Captain Juan José de Hinojosa and María Antonia Inés Ballí de Benavides. Her parents were aristocrats and among the first settlers, which granted them priority rights to land grants and public office. The Hinojosa family moved to Reynosa in 1767. In Reynosa, her father was promoted to Mayor and joined the elite who controlled politics of the jurisdiction.

Rosa María Hinojosa was born in 1752 in what is now Tamaulipas, Mexico. Hinojosa was the sixth of nine children to Captain Juan José de Hinojosa and María Antonia Inés Ballí de Benavides. Her parents were aristocrats and among the first settlers, which granted them priority rights to land grants and public office. The Hinojosa family moved to Reynosa in 1767. In Reynosa, her father was promoted to Mayor and joined the elite who controlled politics of the jurisdiction.

At the time of this post, Phyillis Wanjiru Macharia is a 2L at Penn State Dickinson Law. She is a first-generation Kenyan-American from Orange County, California. She is a Dickinson Law Public Interest Scholar, the Vice President of Fundraising for the Public Interest Law Fund, the Secretary of the Sports and Entertainment Law Society, and will be competing on the National Moot Court team. She still hopes to merge her passions for public interest and intellectual property. Phyillis is also a Research Assistant for Professor Samantha Prince.

At the time of this post, Phyillis Wanjiru Macharia is a 2L at Penn State Dickinson Law. She is a first-generation Kenyan-American from Orange County, California. She is a Dickinson Law Public Interest Scholar, the Vice President of Fundraising for the Public Interest Law Fund, the Secretary of the Sports and Entertainment Law Society, and will be competing on the National Moot Court team. She still hopes to merge her passions for public interest and intellectual property. Phyillis is also a Research Assistant for Professor Samantha Prince. Sally Ride was born on May 26, 1951, in Los Angeles, California. After graduating high school, she went to Stanford University where she would ultimately earn her doctorate in physics. On June 18th, 1983, Ride became the first U.S. woman in space. Apart from being an astronaut, Ride has inspired countless people, as she lived a life committed to science, education, and inclusion. Among those that she inspired is Penn State Dickinson Law’s very own Dean Dodge. Ride was Dean Dodge’s physics and astronomy professor at UC San Diego.

Sally Ride was born on May 26, 1951, in Los Angeles, California. After graduating high school, she went to Stanford University where she would ultimately earn her doctorate in physics. On June 18th, 1983, Ride became the first U.S. woman in space. Apart from being an astronaut, Ride has inspired countless people, as she lived a life committed to science, education, and inclusion. Among those that she inspired is Penn State Dickinson Law’s very own Dean Dodge. Ride was Dean Dodge’s physics and astronomy professor at UC San Diego.  On June 18, 1983, Ride became the first American woman to fly in space. She was an astronaut on the STS-7 space shuttle mission where her job was to use a robotic arm to help put satellites into space. Ride flew on the space shuttle again in 1984. While Ride had a remarkable career at NASA, she also encountered a number of obstacles in her career, including gender-biased questions from reporters.

On June 18, 1983, Ride became the first American woman to fly in space. She was an astronaut on the STS-7 space shuttle mission where her job was to use a robotic arm to help put satellites into space. Ride flew on the space shuttle again in 1984. While Ride had a remarkable career at NASA, she also encountered a number of obstacles in her career, including gender-biased questions from reporters.  In 2003, Ride was added to the Astronaut Hall of Fame, which honors astronauts for their hard work. Until her death on July 23, 2012, Ride continued to help students study science and mathematics. Ride’s legacy lives on and she is still remembered for her work, contribution to science and commitment to inclusion. In 2013, Ride received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Barack Obama. Tam O’Shaughnessy accepted the medal on behalf of Ride.

In 2003, Ride was added to the Astronaut Hall of Fame, which honors astronauts for their hard work. Until her death on July 23, 2012, Ride continued to help students study science and mathematics. Ride’s legacy lives on and she is still remembered for her work, contribution to science and commitment to inclusion. In 2013, Ride received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Barack Obama. Tam O’Shaughnessy accepted the medal on behalf of Ride.  Shila Bayor, at the time of this post, is a rising second-year student at Penn State Dickinson Law. She is from New York City and is a graduate of Bard College. Shila is currently the president of the Business Law Society and secretary for the Black Law Student Union.

Shila Bayor, at the time of this post, is a rising second-year student at Penn State Dickinson Law. She is from New York City and is a graduate of Bard College. Shila is currently the president of the Business Law Society and secretary for the Black Law Student Union.