By: Savannah Wilt

Mary Ellen Pleasant’s beginning, like much of her life, is shrouded in mystery. She was born around 1814 and told people her birthplace was Philadelphia. Others speculated she was either born in Virginia or on a Georgia plantation and likely born a slave. As a young girl she became a domestic servant to a family in Nantucket, Massachusetts where she was innominate around the white people she served. Even then, her ambition burned bright, and she found a way to use her position to create the life she envisioned. Although she never received a formal education, she often pondered what her life would have been if she were afforded the opportunity to obtain an education. Instead, she used her natural intelligence, charisma, and wit to capitalize on her experiences.

Mary Ellen Pleasant’s beginning, like much of her life, is shrouded in mystery. She was born around 1814 and told people her birthplace was Philadelphia. Others speculated she was either born in Virginia or on a Georgia plantation and likely born a slave. As a young girl she became a domestic servant to a family in Nantucket, Massachusetts where she was innominate around the white people she served. Even then, her ambition burned bright, and she found a way to use her position to create the life she envisioned. Although she never received a formal education, she often pondered what her life would have been if she were afforded the opportunity to obtain an education. Instead, she used her natural intelligence, charisma, and wit to capitalize on her experiences.

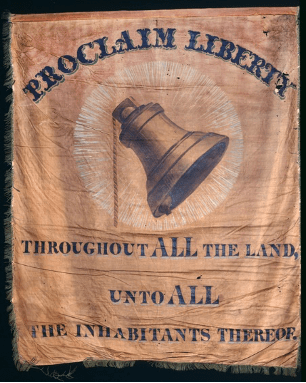

Conductor of the Underground Railroad

Pleasant began her abolitionist work on the Underground Railroad in Massachusetts where she met her first husband. The two continued to help slaves escape from the South until her husband’s death, which left Pleasant with a considerable inheritance. She continued with her work and later married John Pleasant.

Her Secret to Investing: Invisibility

In 1849, newspaper headlines read “Gold! Gold! Gold!” signaling the beginning of the California Gold Rush. The call went out nationwide promising fortune and opportunity to anyone, including people of color. Around the same time Pleasant moved to San Francisco to escape persecution for helping slaves on the Underground Railroad. She took a job as a cook and used her unimposing status to eavesdrop on the wealthy people she served, picking up information she later used to invest parts of her inheritance. Some speculate that Pleasant chose domestic jobs as a cover to hide her true career in investing. Her anonymity allowed her to hear important conversations between prominent business people that others were not privy to. Her portfolio grew and her entrepreneurial activities included restaurants and boarding houses where she employed mostly Black individuals. She was also a prolific investor in real estate and Wells Fargo, and she helped establish the Bank of California. As her wealth grew, she continued to disguise herself as a servant, even in her own establishments, to preserve her anonymity and continue learning from the people around her.

“Here was a colored woman who became one of the shrewdest business minds of the State…She was the trusted confidante of many of the California pioneers such as Ralston, Mills and Booth, and for years was a power in San Francisco affairs.”

Quote by: W. E. B. Du Bois on Mary Ellen Pleasant in The Gift of Black Folk

Dedicated Abolitionist

A famous event in history took place in 1859 when abolitionist John Brown led a raid on a federal armory in Harpers Ferry to spark an armed revolt of enslaved people and destroy the institution of slavery. This is a well discussed and documented event. What is less well-known is who financed John Brown. In 1901, Pleasant was dictating biographical material to Lynn Hudson who compiled factual and speculative materials in the book “The Making of ‘Mammy Pleasant’: A Black Entrepreneur in the Nineteenth-Century San Francisco.” During the interview, she revealed that she was the primary financier of John Brown’s movement against slavery at Harpers Ferry. She contributed $30,000, which in today’s economy amounts to $900,000. Today Pleasant is known for her generous financial contributions, which built up her community and funded resources for the city’s Black population.

Even as she triumphed over racial taboos, she saw and experienced injustice. Her wealth and intellect did not shield her from the effects of racism, and Pleasant continued to fight against institutionalized slavery. She established the Underground Railroad in California and filed multiple lawsuits, bringing attention to the injustices inflicted on people of color. One such case made it all the way to the Supreme Court, which decided in her favor and declared segregation on streetcars to be unconstitutional. She earned the fitting title “Mother of Civil Rights in California” for her relentless fight against racism and her unbreakable drive to achieve equality.

A Final Injustice: Success Marred by Scandal

Pleasant had a long-standing relationship with a white bank clerk named Thomas Bell. Pleasant was secretive about her financial details and it later came to light that many of Pleasant’s assets were in Bell’s name. This included a mansion she designed and built herself. Historians posit that the two teamed up and used Bell’s name for business ventures to overcome what would have been more difficult for Pleasant as a Black woman. After his death, Bell’s widow sued Pleasant for what on paper looked like Bell’s estate and assets. Although Pleasant had evidence to support her ownership, Bell’s widow won control of most of Pleasant and Bell’s shared fortune. Since Pleasant lived with Bell and his family, rumors spread that she was Bell’s mistress and the press propagated other rumors that painted Pleasant’s boarding houses as brothels and accused her of practicing voodoo. The court of public opinion condemned Pleasant, and along with her home and wealth, she lost her good reputation.

In Reverence and Remembrance

Pleasant died in 1904. She is honored in San Francisco with Mary Ellen Pleasant Day and a park dedicated to her memory as the “Mother of Civil Rights in California”. Although the facts of her journey maintain a layer of ambiguity to this day, we can pinpoint her efforts in the fight for equality with clarity. She was bold and audacious until her last day, a sentiment mirrored in her memorable statement:

“I’d rather be a corpse than a coward.”

Savannah Wilt, at the time of this post, is a second-year law student at Penn State Dickinson Law. She is an MBA student at Penn State Harrisburg and is a graduate of York College of Pennsylvania. Savannah is the current Treasurer of the Business Law Society and is pursuing a career assisting small businesses with legal matters.

Savannah Wilt, at the time of this post, is a second-year law student at Penn State Dickinson Law. She is an MBA student at Penn State Harrisburg and is a graduate of York College of Pennsylvania. Savannah is the current Treasurer of the Business Law Society and is pursuing a career assisting small businesses with legal matters.

Sources

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/obituaries/mary-ellen-pleasant-overlooked.html

https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/john-browns-raid-on-harpers-ferry

https://www.nps.gov/people/mary-ellen-pleasant.htm

https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2017/06/02/a-girl-full-of-smartness/

https://allthatsinteresting.com/mary-ellen-pleasant

Photo Sources