By Jacqueline Reid-Walsh

In this blog post I recount a modest adventure in research that involved travelling back to one of my favorite cities, discovering a “new” library (Wellcome Collection) and visiting an old library (the British Library). To my joy they are both on the same street in London! The purpose of my trip was to look at and engage with an early harlequinade published by Robert Sayer on Sept 15, 1767 and based on the 4-part “Beginning, Progress and End of man” first published in 1650 by Bernard Alsop and held in the British Library. This trip came about due to an email from the noted collector of movable books, Ian Alcock. He informed me that my comment in Interactive Books (2018) stated that while the turn-up was listed in Sayer and Bennett’s catalogue of 1775 as number one there was no known copy (based on classic research by Percy Muir 1969 and more recent work by Eric Johnson 2009). Mr. Alcock informed me otherwise.

The Beginning, Progress and End of Man is important in relation to the history of the turn-up book format. The work is listed in the catalog (ca. 1767) of London publisher, print, and mapmaker Robert Sayer with the title Adam and Eve, though no known surviving copy exists (Muir 1969, 210; Johnson 2009, xviii). As a result, as soon as I had some time while still on the ‘right side of the pond’ I popped over to London to check it out at The Wellcome. My project was to examine the Sayer edition, the Alsop edition if possible, and look again at Sayer and Bennett’s Catalogue of 1775 to see again the entry for the turn-up.

My questions are:

- What is the relation between the 1650 edition in the BL and this?

- What is the effect of the kind of illustrations used in both?

- Was the Sayer edition ever published?

- Are there other etched versions of the turn-up published before the Sayer edition?

Since access to the Alsop edition was not possible due to the lasting consequences of the cyber-attack the British Library suffered last fall, I am using images on the images page of my website that I obtained previously from them (see https://sites.psu.edu/play/image-gallery/1650-british/)

I was able however to look at the Sayer and Bennett catalogue and two Sayer harlequinades bound together.

Sayer and Bennett’s Catalogue of 1775 (title page and interior)

Other Sayer harlequinades

My focus here is on the first two questions since to my knowledge the Sayer edition is the first etched edition. As I have discussed elsewhere, I have previously focused on early editions with woodcuts and comparing them with one another. The 1650 text printed by B. Alsop was enlarged into a five-part turn-up and both the words and images reworked by E. Alsop in 1654. There is a 1688/89 edition at The Bodleian Library and an undated 17th century edition held at the Penn State University Libraries (2018, 2023). Regarding the four-part turn-up, there are numerous editions published in America using the title Metamorphosis, or a transformation of pictures: with poetical explanations for the amusement of children. I do not know if the Sayer version is the earliest engraved text but know there are ones published shortly after (e.g. Martin 1802).

Since I am not an expert in early printing techniques my focus is impressionistic: how my perception of a familiar text changes with the mode of illustration. The four-part Sayer version is working from the same basic text as Alsop but with engraved illustrations and new verse; the premise and order of episodes are the same. There is a similarity between the Alsop and Sayer turn-ups materially. Both are uncoloured and there are strict limitations in terms of interactivity. The Alsop 1650 text is attached to a page in a volume of the Thomason tracts. It has uncut flaps so the two sections can only be moved as blocks of paper.

The limitations of the Sayer 1767 edition are different. It is presented as two uncut sheets so has not been assembled. The lines for cutting the images into two are present occurring in the mid sections of the characters. I was able to view the two sheets side by side or one above the other but not able to engage with the turn-up movement at all. In neither case do we know who the author of the verse is or the illustrator. First encountering the artifacts, I experienced a “shock” of the unfamiliar, when a familiar text turns into a new one due to the engraved illustrations. These remediate the bimodal text. Below I briefly describe the text based on my notes and share my general impressions and questions. In a later blog post I will focus on comparing the Adam and Eve/Mermaid images since this is what I have worked on before with the Alsop editions.

Images of the Alsop edition:

Images of the Sayer edition

Part one: Brief description with ponderings

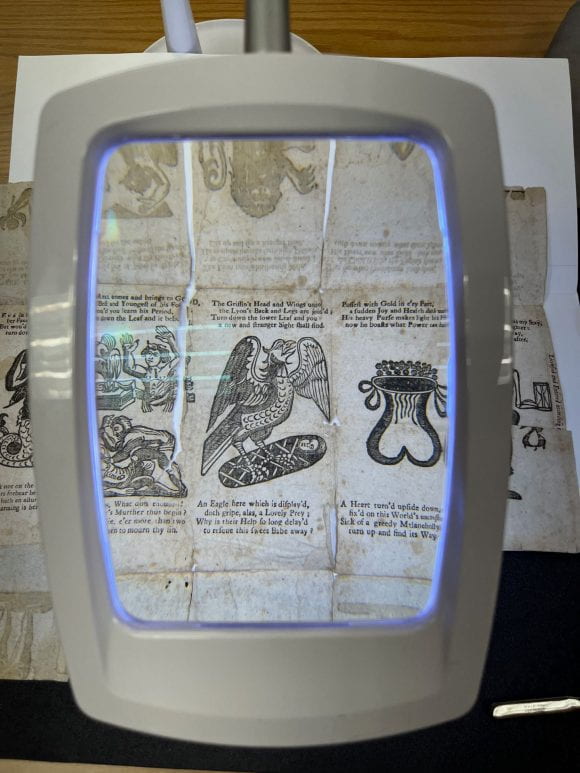

The turn-up is not cut and held in two separate folders. The artifacts have no titles; one is catalogued under a short description “Adam holding a flower; a lion; a youth holding a sword; a rich man with money in his hands. Engraving, 1767,” and the other under “Eve combined with a mermaid; a griffon combined with an eagle holding an infant between its claws; a purse combined with a heart; a skeleton holding an hourglass and an arrow. Engraving, ca. 1757.”

The Wellcome Library has all the images available freely and I have downloaded them. Here are the links. They are listed separately:

For Adam https://wellcomecollection.org/works/dsa4r8n7

For Eve https://wellcomecollection.org/works/t9c35jc2/images?id=g4hgbvwv

The digital images are very helpful, but as always seeing and engaging with the artifact as opposed to the image is a completely different experience. As I described and transcribed the text I had many questions. Was the turn-up never cut? Was it an imperfect copy -since there are some blurring and mistakes and lines visible? Was the turn-up ever printed? If so, why are there apparently no other copies?

These are a few of my observations.

While the artifact has no title, the date of publication is specific: “Publish’d according to Act of Parliament Sept 15th, 1767.” This accords with the undated entry in the 1775 Sayer and Bennett catalogue (see image above).

In terms of the tactile experience, the paper is aged to light tan. It is smooth to touch and feels thickish, substantial. It is difficult to judge the size of the images — I estimate 6 ½” x 3″ per section? The first thing that strikes me visually is the apparently large size of the figures; is it because they are uncut? In the verse the directions “turn up” or “turn down” are inserted into the quatrain either in the last line for the first or in the second line for the second. Underneath is the “moral.”

Looking across both sheets I observe that each of the human figures are elegantly posed and ready to move: on the first sheet the fit Adam has one hand on his hip, holds a flower out in the other, with foot slightly raised as if he is to take a dance step; the young man holding a sword is in a position ready to fence, and the mature man holds a money bag in one hand while gazing down at a money bag for a larger amount cradled like an infant in his other arm.

On the second sheet the well-endowed Eve has well-developed upper body muscles and a powerful, coiling tail, and the skeleton is posed in a cross-feet dance position. Compared to the woodcut versions, all the humanoid figures are elegant and presented in theatrical poses. The images are not caricatures. I am struck by the sophisticated presentation of the adult male figures for they both stand gracefully in relaxed but telling poses. The pose of the skeleton elegantly mirrors that of Adam.

The animal figures are in motion: the lion-man is walking gazing at the viewer, and the eagle is in midflight holding a baby by its claws and is in profile. The emblematic objects, the top of the heart and the heart are oversized and could be balloons while the head of the lion-man looks like a costume in a pantomime. The mermaid would be an effective transformation trick.

These aspects and the implied motion in the stances of all the figures makes me think of a pantomime performance — a harlequinade. Was there a stage harlequinade called Adam & Eve & etc.?

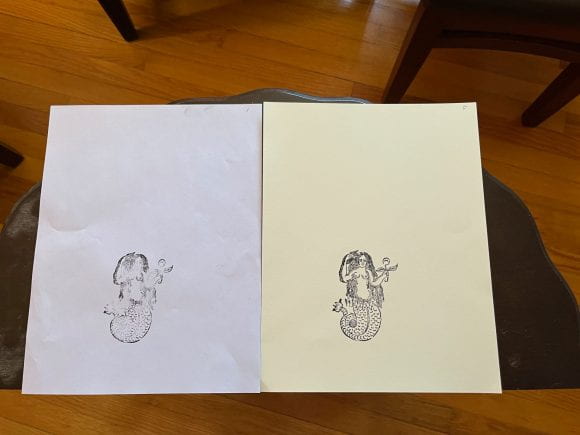

One key similarity with the woodcut editions is there is no figure of Eve. This is fascinating to me. Since I have done some work with conservators with reproduction woodblocks of the Deacon edition at the Bodleian, I realized when I did the printing exercise that there was no Eve block. There are only two: Adam and the mermaid (see https://sites.psu.edu/learningasplaying/2018/02/16/mermaid-at-the-centre/). Realizing this was revolutionary to my understanding of the text. Here I am in a quandary. Again, there is no Eve, just Adam and the mermaid. How was she formed by the etched illustrations? How was the Sayer turn-up assembled? The only clue is looking at the mid-body lines on both sheets indicating where they were to be cut. Focusing on how the turn-up might have been assembled and tackling the mystery of the absent Eve will be the aim of a follow-up blog.

[To be continued]