Last year, a man checked into the Navy Substance Abuse and Recovery Program for alcoholism treatment, but that’s not all he got. The Navy serviceman had been using his newly purchased “Google Glass” in the two months leading up to his admission–for an average of 18 hours a day. He took it off only to sleep and reported feeling irritable when he wasn’t wearing the device, and even described having dreams as if he was viewing them through the window of the glasses. He was treated for withdrawal symptoms and for IAD (internet addiction disorder), a highly contested condition among scientists over whether or not it exists. Unlike alcohol or drug addiction, there is no chemical component or intake–but can an “addiction” to the internet be as strong?

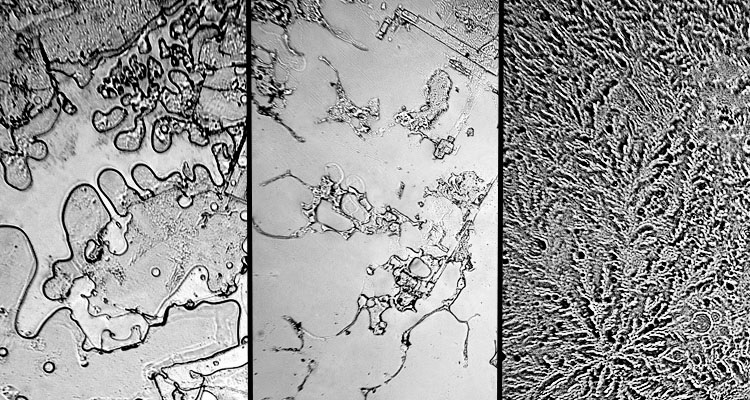

The question lies in whether or not one can truly be addicted to the Internet, or if constant internet use is a symptom of another underlying disorder, such as depression, anxiety, or impulse control disorders. It can be compared to food addiction/compulsive overeating stemming from depression–you are not really addicted to food, but you eat to help control symptoms of depressive disorders. IAD is not yet classified as it’s own disorder by authorities such as the American Psychological Association or the American Medical Association, but as our daily lives are coming to rely more and more on connectivity, more and more research is being done. A 2012 study (that brought attention to many major new outlets) scanned the brains of people “diagnosed” with IAD (based on the answers given to questions such as “do you feel the need to use the Internet with increasing amounts of time in order to achieve satisfaction?”), and found reductions in the volume of white matter, or the areas of the brain where connections are made. These brain alterations actually mirror the brains of people who are addicted to drugs like heroin. However, the results of this study are preliminary and should be used only as inspiration for further research. The sample size was extremely small (17 adolescents) and the “diagnosis” of having internet addiction was based on self-reported surveys (not to mention that as this disorder is not yet classified, there are no universal medical standards for making such diagnoses).

It wasn’t until 1956 the American Medical Association recognized alcoholism as an illness, and as we know from class, it took decades for the negative effects of cigarettes to come to light. While staying on the internet all day won’t give you lung cancer or liver cirrhosis, it may be prudent of parents to limit their children’s internet time in order to develop healthy habits of restraint.